Copyright © Stephen E. Jones[1]

This is #49, "Prehistory of the Shroud (6)," of my series, "The evidence is overwhelming that the Turin Shroud is Jesus' burial sheet!" This post is based on my "Chronology of the Turin Shroud: Eleventh century." For more information about this "overwhelming" series, see the "Main index #1."

[Main index #1] [Previous: Prehistory of the Shroud (5) #48] [Next: History of the Shroud (1) #50]

A major criticism of Ian Wilson's theory that the of Image of Edessa/ Mandylion was the Shroud folded in eight, with only the face one-eighth panel visible (see my "Tetradiplon and the Shroud of Turin"), is that there should be, but isn't, a circular area around the Shroud face which is darker than the rest of the cloth:

Mandylion was the Shroud folded in eight, with only the face one-eighth panel visible (see my "Tetradiplon and the Shroud of Turin"), is that there should be, but isn't, a circular area around the Shroud face which is darker than the rest of the cloth:

"Mr Wilson argues that the Mandylion was the Shroud of Christ so folded up and protected by ornamental trellis that only the image of the face was displayed ... [But] "If the Shroud spent more than half its life as the Mandylion, there should be a circular area around the face of Christ which is more yellowed than the rest of the cloth: but this is not the case"[MP78, 37].In my next post I will present evidence that there is a circular area around the Shroud face, which has been hiding in plain sight!

c. 1000 Assumed appearance of the Russian Orthodox cross, with its angled footrest, or suppedaneum[BW57, 47], with the left side higher than the right[BA34, 65]. This

[Right (enlarge[TDC]): Russian cross with angled footrest, late 12th century.]

followed the conversion to Christianity in 988 of Vladimir the Great (978-1015)[VGW] and the subsequent Christianisation of Russia, when missionaries came from Constantinople[BA34, 65-66] bringing a copy of the full-length Shroud, in `icon evangelism'[WI10, 184]. This matches the Shroud, in  that the man on the Shroud's left leg (which when facing the Shroud appears to be his right leg because of left-right reversal[BA34, 64]), appears to be shorter than the other[PM96, 196]. This is due

that the man on the Shroud's left leg (which when facing the Shroud appears to be his right leg because of left-right reversal[BA34, 64]), appears to be shorter than the other[PM96, 196]. This is due

[Left (enlarge[LM10a]): The man on the Shroud's apparent right leg (left leg because of left-right reversal) appears to be shorter than his right.]

to his left foot having been superimposed over his right[PM96, 196], and both feet fixed by a single nail[BA34, 64]. The man's left leg was therefore bent more and remained fixed in that position after death by rigor mortis[PM96, 196]. This presumably is the source of the 11th century Byzantine legend that Jesus actually had one leg shorter than the other and therefore was lame[RC99, 111].

c. 1000b Closely related to the Russian cross is the "Byzantine curve"

[Right (enlarge): "Byzantine Crucifix of Pisa," ca. 1230[BMW]. Note that Christ's right leg (corresponding to the Shroud's left leg) is shorter than the other leg and His body is curved (the "Byzantine curve") to compensate.]

in Byzantine Christian iconography[BA34, 66]. After the year 1000, a striking change occurred in Byzantine depictions of Christ on the Cross[BA34, 66-67]. Christ's two feet were nailed separately at the same level but his left leg is bent which meant that Jesus' body needed to curve to His right to compensate[BA34, 67]. This "Byzantine curve" became the established form of Eastern depictions of Christ at the beginning of the eleventh century and made its way also into the West and became the recognized form in Italy in the early mediaeval period[BA34, 67-68]. As with the strange design of the Russian cross, so this strange belief that Jesus had to have a curved body on the Shroud because one leg was shorter than the other[BA34, 68], has its most likely common origin in the Shroud[PM96, 195]. But then that means the full-length Shroud was known in the Byzantine world (the centre of which was Constantinople), soon after the year 1000, nearly three centuries before 1260, the earliest radiocarbon date of the Shroud[WI98, 141], and and more than three and a half centuries before the Shroud first appeared in c. 1355, in undisputed history at Lirey, France[DT12, 181-182; OM10, 52; WI10, 222, 228]!

1011 Pope Sergius IV (r. 1009-12) consecrates an altar in Rome dedicated to the sudarium[WI98, 269; GV01, 7; OM10, 37]. This is thought to be a reference to the coming to Rome of its Veil of Veronica[BW57, 40; WI79, 109], which was purported to be

[Above (original): Excerpt from a poor quality distance photograph of Rome's Veronica icon[SPV], which the Vatican now refuses to allow to be seen or photographed up close because it has so deteriorated[BW57, 41; WI91, 183-187; OM10, 37; WI98, 63].]

an imprint of Jesus' face on the veil of a Jerusalem woman named Veronica who supposedly wiped Jesus' bloody and sweaty face with it as He was being led to the site of His crucifixion[WI79, 97, 106; SH81, 25-26; SD91, 265-266; WI91, 25; GV01, 7; OM10, 36]. But there is no mention of that in the Gospel accounts (Mt 27:31-35; Mk 15:20-25; Lk 23:26-33; Jn 19:16-18)[BW57, 12; GV01, 7]. That there never was a woman called Veronica is evident in the name itself, which is a compound of Latin vera "true" + Greek eikon "image") = "true image"[SH81, 25-26; HJ83, 71; CJ84, 53; PM96, 191; RC99, 59; GV01, 7]. The Veronica's veil legends seem to have arisen in 7th and 8th centuries, when knowledge of the Edessa Cloth/Shroud image had become widespread[MW83, 287; BM95, 50; BW57, 41; AM00, 265; OM10, 37]. In the early twentieth century, Joseph Wilpert (1857-1944), a German Catholic priest and archaeologist, examined the Vatican's Veronica icon in St Peter's Basilica and found on it brown stains but no clear image[BW57, 41; AM00, 265; OM10, 37]. Similarly, Hungarian artist Isabel Piczek (1927–2016) in 1946, when still a teenager, was surprisingly shown the Veronica in St. Peter's, and as she described it:

"On it was a head-size patch of colour, about the same as the [Turin] shroud, slightly more brownish. By patch, I do not mean that it was patched, just a blob of a brownish rust colour. It looked almost even, except for some little swirly discolorations ... Even with the best imagination, you could not make any face or features out of them, not even the slightest hint of it"[WI91, 185].Earlier artists' copies of the Veronica icon indicate it was a copy of the face on the Cloth of Edessa/Shroud[BW57, 40] specially made for Rome shortly before the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches went their separate ways[BM95, 35; PM96, 191; WI98, 269-270]. Indeed, when Makarios of Magnesia (4th century)[AM00, 265], retold the Veronica legend, he called her a "Princess of Edessa"[SD91, 195]! This supports my proposal that, the Veronica story may be "a contemporary parallel to [or even earlier than] the Abgar V story of Jesus wiping his face on a towel [see "50"], to explain how Jesus' image came to be on the Image of Edessa (the Shroud tetradiplon = `four-doubled')" (see my 06Mar17). It had been claimed that Rome's Veronica icon disappeared when the troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (r. 1519-1556) mutinied and sacked Rome and the Vatican in 1527[WI79, 107; WM86, 107, 129; AM00, 265; OM10, 37]. But in 1616-17 six official faithful "tone for tone, blotch for blotch" copies of the Veronica in St Peter's were commissioned by Pope Paul V (r. 1605-21) to be painted by an amateur artist who was also a canon of St Peter's, Pietro Strozzi[WI91, 106-113; OM10, 37]. And at least three of Strozzi's copies have survived: "The Holy Face of Vienna," "The Holy Face of San Silvestro," and "The Holy Face of Genoa" (see my 03Sep12)[WI91, 111-114]. So this 1527 looted Veronica was evidently only one of the many copies of that icon[WI91, 47; AM00, 265; BJ01, 87].

c. 1050a The mid-eleventh-century Old French "Life of Saint Alexis"[ARW], the first masterpiece of French literature, contains  the passage:

the passage:

"Then he [St. Alexius (-417)] went off to the city of Edessa Because of an image he had heard tell of, which the angels made at God's commandment" (my emphasis)[WI87, 14]

[Left (enlarge[TCF]): Miniature and text of the "Chanson de St Alexis" or "Vie de St Alexis," in the St. Albans Psalter (c. 1120-1145)[SLB].]

As philologist Linda Cooper has shown in a scholarly paper[CL86], the "image" referred to is the Image of Edessa, and from the various versions of St. Alexis's life it is clear that this was the Shroud (my emphasis)[WI87, 14]. See "977" for a 10th century "Life of St. Alexis" which used the word "sindon," the same word used in the Gospels for Jesus' burial shroud[WI98, 269] (Mt 27:59; Mk 15:46; Lk 23:53)!

c. 1050b Eleventh-century mosaic bust of Christ Pantocrator, i.e. "Ruler of all"[RC99, 110; ZS92, 1093-94], in the narthex of the Katholicon church (c. 1010) within the Hosios Loukas  monastery[HL24] near the town of Distomo, Greece[HLW].

monastery[HL24] near the town of Distomo, Greece[HLW].

[Right (enlarge[FHW]): Christ Pantocrator, c. 1050, Hosios Loukas monastery, Greece[HLW].]

The late art historian, Professor Kurt Weitzmann (1904-93), who specialised in Byzantine and medieval art[KWW], noted that this icon had facial "subtleties" similar to the sixth-century Christ Pantocrator icon portrait in St. Catherine's monastery, Sinai[WM86, 107] [see "550"]. In particular Prof. Weitzmann noted:

"...the pupils of the eyes are not at the same level; the eyebrow over Christ's left eye is arched higher than over his right ... one side of the mustache droops at a slightly different angle from the other, while the beard is combed in the opposite direction ... Many of these subtleties remain attached to this particular type of Christ image and can be seen in later copies, e.g. the mosaic bust in the narthex of Hosios Lukas over the entrance to the catholicon ... Here too the difference in the raising of the eyebrows is most noticeable ..." (my emphasis)[WK76].

Those facial "subtleties" that Prof. Weitzmann noted were "attached to this particular type of Christ image and can be seen in later copies" are Vignon markings (see 11Feb12) which are all found on the Shroud (see 27Jul17)!

1075 On 14 March the ark or chest (Arca Santa) in which the

[Above (enlarge)[ASW]: The Holy Chest (or Arca Santa) in which the Sudarium of Oviedo was transported from Jerusalem in 614[BJ01, 194], via Alexandria[BJ01, 194], to Cartagena and Seville in Spain in 616[BJ01, 194]; taken to the Monastery of San Vicente near Oviedo in 761[BJ01, 195], deposited in the Holy Chamber (Camara Santa), which is within today's Oviedo Cathedral, by King Alfonso II (r. 791-842) in c.812[BJ01, 195], opened by Bishop Ponce (r. 1025–28) in 1030[BJ01, 195-96] and again opened by King Alfonso IV (r. 1065–1109) in 1075[BJ01, 196].]

Sudarium of Oviedo was kept was officially opened in the presence of King Alfonso VI (r. 1065-1109), his sister Doña Urraca (c.1033–1101), Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar (c. 1040–99) (aka El Cid) and a number of bishops[GM98, 17]. This official act was recorded in a document which is now kept in the archives of the cathedral in Oviedo[GM98, 17]. But

[Above: "Comparison of the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin"[BJ01, 122]. "The most striking thing about all the stains [on the Sudarium of Oviedo] is that they coincide exactly with the face of the image on the Turin Shroud" (my emphasis)[GM98, 27].]

as we saw in ["614"], the bloodstains on the face and back of the head of the Sudarium of Oviedo are so similar in appearance to those on the corresponding parts of the Shroud, that the two cloths must have been in contact with the same wounded body within the same short time period[AA96, 83]. And since the Sudarium has been in Spain since the early seventh century, and certainly since 1075, this is further evidence that the "mediaeval ... AD 1260-1390 radiocarbon date of the Shroud[DP89, 611] is wrong[AA0a, 124]!

c. 1080 Eleventh-century Christ Pantocrator mosaic in the dome  of the monastery church of Daphni near Athens, Greece[MR86, 77]. It has 13 of the 15

of the monastery church of Daphni near Athens, Greece[MR86, 77]. It has 13 of the 15

[Left (enlarge[FDW]): Christ Pantocrator mosaic in the dome of Daphni Monastery, Greece[DMW].]

Vignon markings [MR86, 77]. Some of the markings (for example, the three-sided, or topless, square) are stylized, having been rendered more naturalistic by a very competent artist[WI79, 104; WR10, 101].

c. 1087 The Pantocrator in the apse of Sant'Angelo in Formis church, near Capua, Italy, I have dated c. 1087. That is because the "church was built in the eleventh century by Desiderius, the abbot of Monte Cassino," who died in 1087 as Pope Victor III (c. 1026–87)[PVW]:

"The church was built in the eleventh century by Desiderius, the abbot of Monte Cassino ... the decoration was carried out by Byzantine (Greek) artists hired from Constantinople and the decoration of Sant'Angelo displays a mingling of the Byzantine (Eastern) and Latin (Western) traditions. The frescos were painted by Greek artists and by Italian pupils trained in their methods"[SFW].This "Christ enthroned" mosaic[WI91, 47] has 14 out of the 15 Vignon

[Right (enlarge): Extract of Christ's face which is part of a larger 11th century mosaic in the church of St. Angelo in Formis, Capua, Italy[WM86, 110A].]

markings that are on the Shroud[WI91, 47], many of which are just incidental blemishes on the cloth[WI79, 102]. These include:

"... a transverse line across the forehead, a raised right eyebrow, an upside-down triangle at the bridge of the nose, heavily delineated lower eyelids, a strongly accentuated left cheek, a strongly accentuated right cheek, and a hairless gap between the lower lip and beard ..."[WI91, 165].One of these, the upside-down triangle at the bridge of the nose (VM 3)[WI78, 82E] is particularly important because it has no logic as a natural feature of the

[Left (enlarge): Upside-down triangle at the bridge of the nose on the Shroud, just below the base of the `topless square'[LM10b].]

face, yet it recurs on several other pre-1260] depictions of Jesus' face. In this eleventh-century Pantocrator in the dome of the church at Daphni, near Athens, being a mosaic, pieces of black material have been specially selected and arranged into the shape of a triangle[WI91, 165]!

c. 1090 Late eleventh/early twelfth century Byzantine ivory carving

[Above (enlarge): "Scenes from the Passion of Christ." 5-1872, Victoria and Albert Museum, London[SP04].]

part of a larger carved ivory panel in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London[WI79, 160; WI91, 151; WI98, 147, 270. See "c. 1090"]. Jesus' arms are crossed awkwardly at the wrists, right over left, covering his loins[WI79, 160; WI10, 182-183], exactly as they are on the Shroud[WI91, 151; WI98, 270; WI10, 183]. And Jesus is lying on a double-length cloth[WI91, 151; WI98, 270]. Yet this is a late 11th/early 12th century Byzantine icon[WI98, 147], an early example of the genre which the Byzantine Greeks called Threnos[WI91, 151; PM96, 195], or Lamentation, the main feature of which is Jesus wrapped in a large cloth compatible with today's Turin Shroud[WI10, 182]. This is further proof beyond reasonable doubt that the Shroud already existed more than a century before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud!

1092 A letter dated 1092 purporting to be from the Byzantine Emperor  Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118) (aka Alexius I Comnenus) to Robert II of Flanders (c.1065- 1111)[WI79, 166-167]. In the letter the Emperor

Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118) (aka Alexius I Comnenus) to Robert II of Flanders (c.1065- 1111)[WI79, 166-167]. In the letter the Emperor

[Right (enlarge): Portrait of Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus (1056-1118), from a Greek manuscript [ANK].]

appealed for help to prevent Constantinople falling into the hands of the pagans[RG81, xxxv; SD89b, 318.]. The letter listed the relics "of the Lord" in Constantinople including, "the linen cloths [linteamina] found in the sepulchre after his Resurrection"[CN89, 11-12; DT12, 177]. Although some historians regard the letter as a forgery[WI79, 314 n31], it may not be, since Robert had made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1086 and had spent some time with Alexius I in Constantinople, and there is no reason why the two had not remained in touch[CD89, 17]. Besides, even if Alexius I did not himself write the letter, this need not invalidate its description of the relics which were then in the imperial collection[WI79, 314 n31]. See "1095" next on the appeal by the same Emperor for Western help to prevent Anatolia from falling into the hands of Muslim forces.

1095 Start of the First Crusade (1095–1099) which sought to regain the Holy Land taken in the Muslim conquests of the Levant (632–661)[FCW]. The crusade was called for by Pope Urban II (r. 1088-99), in response to an appeal by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118) who requested western help to repel the invading Seljuk Turks from Anatolia[FCW]. See above on the 1092 appeal by the same Emperor for Western help to prevent Constantinople from falling into the hands of Muslim forces. The crusade culminated in the recapture of Jerusalem in 1099[SJW]. In 1098 Edessa was captured by Christian forces under Baldwin of Boulogne (1058-1118) who became the first ruler of the County of Edessa and then the first King of Jerusalem (r. 1098–1100)[BNW].

[Left (enlarge): "Baldwin of Boulogne entering Edessa in February 1098," by J. Robert-Fleury (1840)[BBW].]

Edessa became an important part of the Crusader presence in the Middle East[OM10, 33] until its recapture by Muslim forces in 1144[SEW]. [See future "1144"]. An important consequence for Shroud history of the Christian capture of Edessa in the First Crusade is that Byzantine texts about Edessa became better known in the West[SD02, 6]. Among these were the Abgar V story[SD89av, 88] [See future "c.1130"].

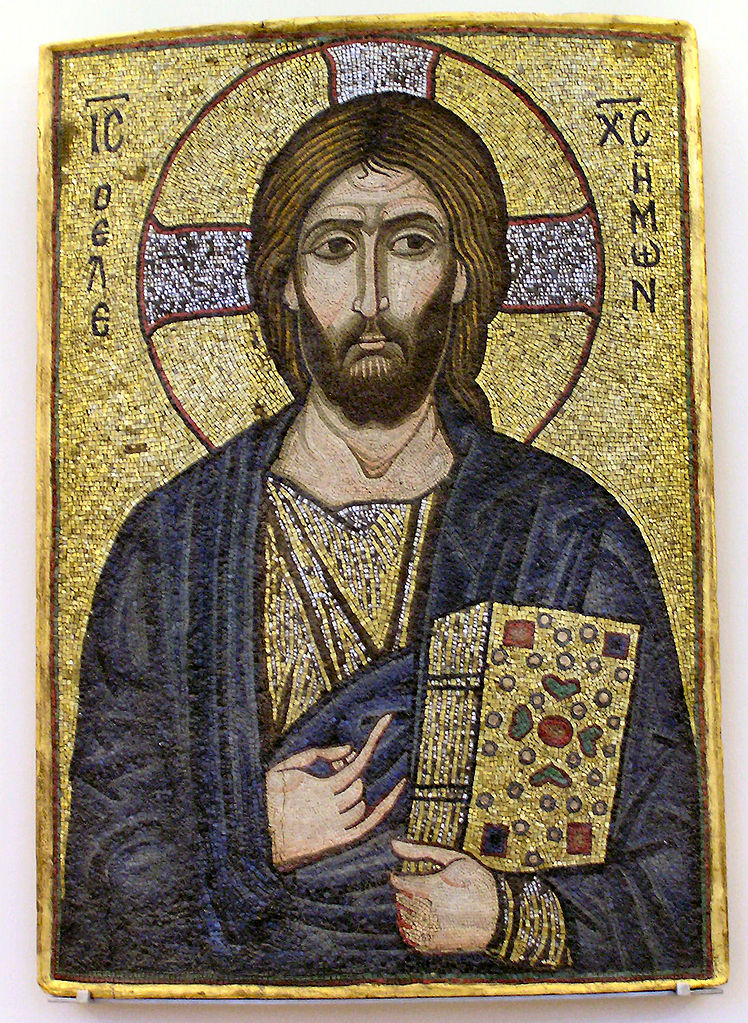

c. 1100 Late eleventh century portable mosaic, "Christ the Merciful"[WI79, 160H; MR80, 114; AM00, 126], in the former Ehemals Staatliche Museum], now Bodemuseum, Berlin.

Merciful"[WI79, 160H; MR80, 114; AM00, 126], in the former Ehemals Staatliche Museum], now Bodemuseum, Berlin.

[Right (enlarge): "Christ the Merciful" mosaic icon (1100-50)[CTM].]

By my count this 11th century icon has 12 (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) of the 15 Vignon markings including a wisp of hair where the reversed `3' bloodflow is on the Shroud, a topless square, wide open staring eyes, a forked beard and a line across the throat, but they are more stylized[WI79, 104].

"... if the radiocarbon dating is to be believed, there should be no evidence of our Shroud [before 1260]. The year 1260 was the earliest possible date for the Shroud's existence by radiocarbon dating's calculations. Yet artistic likenesses of Jesus originating well before 1260 can be seen to have an often striking affinity with the face on the Shroud ..."[WI98, 141]!Notes:

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to extract or quote from any part of it (but not the whole post), provided the extract or quote includes a reference citing my name, its title, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

Bibliography

AA96. Adler, A.D., 1996, "Updating Recent Studies on the Shroud of Turin," in AC02, 81-86.

AA0a, 124. Adler, A.D., 2000, "The Shroud Fabric and the Body Image: Chemical and Physical Characteristics," in AC02, 113-127.

AC02. Adler, A.D. & Crispino, D., ed., 2002, "The Orphaned Manuscript: A Gathering of Publications on the Shroud of Turin," Effatà Editrice: Cantalupa, Italy.

AM00. Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY.

ANK. "Alexios I Komnenos," Wikipedia, 8 November 2024.

ARW. "Alexius of Rome," Wikipedia, 25 October 2024.

ASW. "Arca Santa," Wikipedia, 14 January 2022.

BA34. Barnes, A.S., 1934, "The Holy Shroud of Turin," Burns Oates & Washbourne: London.

BA91. Berard, A., ed., 1991, "History, Science, Theology and the Shroud," Symposium Proceedings, St. Louis Missouri, June 22-23, The Man in the Shroud Committee of Amarillo, Texas: Amarillo TX.

BBW. "File:Baldwin of Boulogne entering Edessa in Feb 1098.JPG," Wikipedia, 18 November 2017.

BJ01. Bennett, J., 2001, "Sacred Blood, Sacred Image: The Sudarium of Oviedo: New Evidence for the Authenticity of the Shroud of Turin," Ignatius Press: San Francisco CA.

BM95. Borkan, M., 1995, "Ecce Homo?: Science and the Authenticity of the Turin Shroud," Vertices, Duke University, Vol. X, No. 2, Winter, 18-51.

BMW. "Byzantine Master of the Crucifix of Pisa," Wikipedia, 2 May 2024.

BNW. "Baldwin I of Jerusalem," Wikipedia, 20 November 2024.

BW57. Bulst, W., 1957, "The Shroud of Turin," McKenna, S. & Galvin, J.J., transl., Bruce Publishing Co: Milwaukee WI.

CD89. Crispino, D.C., 1989, "Questions in a Quandary," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 31, June, 15-19.

CJ84. Cruz, J.C., 1984, "Relics: The Shroud of Turin, the True Cross, the Blood of Januarius. ..: History, Mysticism, and the Catholic Church," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN.

CL86. Cooper, L., 1986, "The Old French Life of Saint Alexis and the Shroud of Turin," Modern Philology, Vol. 84, No. 1, August, 1-17.

CN89. Currer-Briggs, N., 1989, "Letters," BSTS Newsletter, No. 22, May, 11-12.

CTM. "Christ the Merciful" (1100-50), mosaic icon, in the Museum of Byzantine Art, Bode Museum, Berlin, Germany: Wikipedia (translated by Google).

DMW. "Daphni Monastery," Wikipedia, 7 May 2017.

DP89. Damon, E., et al., 1989, "Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin," Nature, Vol. 337, 16 February, 611-615, 611.

DT12. de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London.

FCW. "First Crusade," Wikipedia, 4 November 2024.

FDW. "File:Meister von Daphni 002.jpg," Wikimedia Commons, 17 July 2024.

FHW. "File:Hosios Loukas (narthex) - East wall, central (Pantocrator) 01.jpg," Wikimedia Commons, 2 February 2021.

GM98. Guscin, M., 1998, "The Oviedo Cloth," Lutterworth Press: Cambridge UK.

GV01. Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL.

HJ83. Heller, J.H., 1983, "Report on the Shroud of Turin," Houghton Mifflin Co: Boston MA.

HL24. "Hosios Loucas (Stiris)," Pausanias Project, 2024.

WI98, 269; GV01, 7; OM10, 37. Wilson, 1998, 269; Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, 7; Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK, 37.

HLW. "Hosios Loukas," Wikipedia, 2 October 2024.

KWW. "Kurt Weitzmann," Wikipedia, 13 September 2024.

LM10a. Extract from Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002 Vertical".

LM10b. Extract from Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Face Only Vertical.," Sindonology.org.

MP78. McNair, P., 1978, "The Shroud and History: Fantasy, Fake or Fact?," in JP78, 21-40.

MR80. Morgan, R.H., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia.

MR86. Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY.

MW83. Meacham, W., 1983, "The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology," Current Anthropology, Vol. 24, No. 3, June, 283-311.

OM10. Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK.

PM96. Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1996, "The Enigma of the Shroud: A Challenge to Science," Scerri, L.J., transl., Publishers Enterprises Group: Malta.

PVW. "Pope Victor III," Wikipedia, 10 November 2024.

RC99, Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN.

RG81. Ricci, G., 1981, "The Holy Shroud," Center for the Study of the Passion of Christ and the Holy Shroud: Milwaukee WI.

SD89a, 88. Scavone, D.C., 1989, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA.

SD89b. Scavone, D., 1989, "The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople: The Documentary Evidence," in SR89, 311-329.

SD91. Scavone, D.C., 1991, "The History of the Turin Shroud to the 14th C.," in BA91, 171-204.

SD99. Scavone, D.C., 1999, "Greek Epitaphoi and Other Evidence for the Shroud in Constantinople up to 1204," in WB00, 204-205.

SD02. Scavone, D.C., 2002, "Joseph of Arimathea, the Holy Grail and the Edessa Icon," Collegamento pro Sindone, October, 1-25.

SEW. "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Edessa_(1144)," Wikipedia, 20 November 2024.

SFW. "Sant'Angelo in Formis," Wikipedia, 28 May 2024.

SH81. Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1981, "Verdict on the Shroud: Evidence for the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ," Servant Books: Ann Arbor MI.

SJW. "Siege of Jerusalem (1099)," Wikipedia, 14 November 2024.

SLB. "St. Albans Psalter," Wikipedia, 29 May 2024.

SP04. "Scenes from the Passion of Christ; The Crucifixion, the Deposition from the Cross, The Entombment and the Lamentation," Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 5 January 2004.

SPV. "St. Peter's Basilica: St Veronica Statue," February 6, 2010.

SR89. Sutton, R.F., Jr., 1989, "Daidalikon: Studies in Memory of Raymond V Schoder," Bolchazy Carducci Publishers: Wauconda IL

TCF. "The Chanson of St Alexis: Page 57 Commentary," The St Albans Psalter Project, University of Aberdeen, 2003.

TDC. The Adoration of the Cross," 1130-1200, The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia, "Fine Art Images: Icons, Murals, Mosaics," n.d.

VGW. Vladimir the Great," Wikipedia, 4 November 2024.

WB00. Walsh, B.J., ed., 2000, "Proceedings of the 1999 Shroud of Turin International Research Conference, Richmond, Virginia," Magisterium Press: Glen Allen VA.

WI87. Wilson, I., 1987, "Recent Publications," British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter 16, May.

WI78. Wilson, I., 1978, "The Turin Shroud," Book Club Associates: London.

WI79. Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus Christ?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition.

WI91. Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London.

WI98. Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY.

WI10. Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London.

WK76. Weitzmann, K., 1976, "The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Icons," Princeton University Press: Princeton NJ, 15, in WM86, 107].

WM86, Wilson, I. & Miller, V., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London.

WR10. Wilcox, R.K., 2010, "The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery," [1977], Regnery: Washington DC.

ZS92. Zodhiates, S., 1992, "The Complete Word Study Dictionary: New Testament," AMG Publishers: Chattanooga TN, Third printing, 1994.

Posted 9 November 2024. Updated 11 February 2025.

No comments:

Post a Comment