This is part 6, "The Image of Edessa" (2) of my critique of historian Charles Freeman's, "The Turin Shroud and the Image of Edessa: A Misguided Journey," May 24, 2012 [pages 5-6]. Freeman's paper's words are bold. See previous parts 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

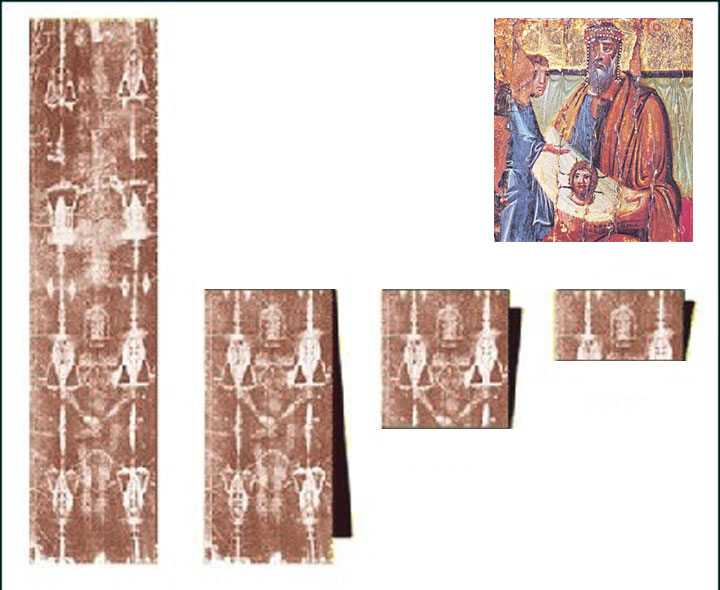

[Above (click to enlarge): The Image of Edessa (11th century), Sakli church, Goreme, Turkey: Wilson, I., "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam: London, 2010, plate 22b. Again note that Jesus' head appears in landscape aspect, which is obtained by doubling the Shroud of Turin four times, as Wilson points out in his book, but Freeman conceals it from his readers:

"But we still come back to a key question. Even if we accept that the Image of Edessa was a piece of cloth bearing Christ's imprint, so far that is all we have heard about it, that it bore the face of Jesus. Why should we believe it was a cloth of the fourteen-foot dimensions of the Shroud? And what evidence do we have that this Edessa cloth actually was the Shroud? In the case of the Image of Edessa's dimensions, one important indicator is to be found in one of the very first documents to provide a 'revised version' of the King Abgar story in the wake of the cloth's rediscovery. The document in question is the Acts of Thaddaeus, dating either to the sixth or early seventh century. Although its initially off-putting aspect is that it 'explains' the creation of the Image as by Jesus washing himself, it intriguingly goes on to describe the cloth on which the Image was imprinted as tetradiplon `doubled in four'. It is a very unusual word, in all Byzantine literature pertaining only to the Image of Edessa, and therefore seeming to indicate some unusual way in which the Edessa cloth was folded. So what happens if we try doubling the Shroud in four? If we take a full-length photographic print of the Shroud, double it, then double it twice again, we find the Shroud in eight (or two times four) segments, an arrangement seeming to correspond to what is intended by the sixth-century description ... And the quite startling finding from folding the Shroud in this way is that its face appears disembodied on a landscape-aspect cloth exactly corresponding to the later 'direct' artists' copies of the Image of Edessa." (Wilson, 2010, p.140)]

[Above (enlarge): How the Shroud "doubled in four" (Greek tetradiplon) results in Jesus' face in landscape aspect, exactly as it is in depictions of the Image of Edessa, like that in the Sakli church above: Dan Porter, "The Definitive Shroud of Turin FAQ: Tetradiplon" (2009) [No longer online. See my 15Sep12]. Wilson has a similar set of diagrams in his book on the opposite page 141, to illustrate his point above, but it is only in black and white. But again Freeman conceals this crucial information from his readers. And perhaps even from himself?]

Freeman resumes his fallacious argument that because there are many copies of the Image of Edessa (i.e. the Shroud of Turin doubled-in-four), therefore there cannot be an original from which all those copies ultimately derive:

The late sixth century saw the emergence of many such images and they have been studied in detail by Hans Belting in his authoritative Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, Chicago, 1994. This period was one when the first intimations of iconoclasm were being heard. Could Christ be represented in images? The response was the appearance of a number of paintings that were said to be acheiropoieton, `not made by human hands'. Most, but not all, were images left by the living Christ on a cloth, though there were others such as the traces left by Christ's body on the pillar against which he was scourged. So Christ had apparently shown, during his own lifetime, that he could be represented and so the iconoclasts could be resisted. Yet the emergence of these images came over five hundred years after the life of Christ! Each acheiropite or image therefore had to develop a story, telling how had it been created and where had it been in the intervening five hundred years. In the case of the Image of Edessa there were two or three stories, that it had been painted by the court painter of king Abgar or, more usually, that Christ himself had wiped his face with a cloth and the image had been imprinted.Freeman continues to mislead his readers by confusing the Image of Edessa with the "Veil of Veronica" story that "Christ himself had wiped his face with a cloth and the image had been imprinted" on

[Above: Poor quality distance photograph of the Vatican's Veronica, which the Vatican apparently refuses to allow to be photographed close up, presumably because they know it is merely a deteriorated copy of the Mandylion/Image of Edessa: Veronica's Veil]

it. But as Freeman must know if he has read Ian Wilson's latest book, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved" (2010), which Freeman implies he has (under an alternative subtitle):

"Despite many years of research de Wesselow uncritically accepts much of the work of the veteran Shroud researcher Ian Wilson whose latest volume, The Shroud, Fresh Light on the 2000-year-old Mystery, Bantam Books, 2011, is used here" (page 1)the Vatican's Veronica is merely "an official 'copy' for the western world of something that was altogether older and more mysterious being preserved at that time in the Byzantine east, in Constantinople", namely the Shroud:

"For westerners, the most familiar example of the genre will probably be the famous Veronica cloth. This is popularly associated with the story of a woman called Veronica wiping Jesus's face with her veil as he struggled with his cross through Jerusalem's streets on his way to be crucified. According to the story, Jesus's 'Likeness' became miraculously imprinted on Veronica's veil. Dozens of medieval and Renaissance artists depicted the scene, and thousands of Roman Catholic churches have it included among their 'Stations of the Cross', leading many to suppose the story must be in the gospels ... In fact the story in this form dates no earlier than the late Middle Ages, seeming to have been invented to spice up 'miracle play' dramatizations of the Passion story. In a twelfth-century version" there was no woman called Veronica, though at that time the canons of St Peter's, Rome were already keeping under close guard a cloth that was supposed to be the Vera Icon or 'True Likeness' of Jesus. Reputedly this likeness was imprinted not during Jesus's carrying of the cross but when he wiped his face after the 'bloody sweat' in the Garden of Gethsemane. A popular attraction for pilgrimages to Rome during the Middle Ages, this cloth can be traced historically no earlier than the eleventh century. It seems to have been an official 'copy' for the western world of something that was altogether older and more mysterious being preserved at that time in the Byzantine east, in Constantinople." (Wilson, 2010, pp.110-111).So, as previously observed, either Freeman has not read Wilson's book thoroughly (which would be scholarly incompetence) or he has read the above, but is concealing it from his readers (which would be scholarly dishonesty).

Freeman continues with irrelevant red herrings about "Greek myths" and "Veronica's Veil" as part of his overall strategy to depict the Shroud as just another fake relic:

Varying legends were common, just as many Greek myths have several versions. The Abgar legends then went on to claim that the image had come to Edessa in the first century where it had been hidden in the city wall before its `reappearance' in the sixth century. Similar legends tell of images or other relics from the first century being buried (and often revealed in a dream) or stolen by Jews in the early days after the Crucifixion. Veronica's Veil was supposed to have been brought to Rome by Veronica after she had [6] wiped Christ's face with it and then presented it to the emperor Tiberius. (In fact Veronica was simply a corruption of Vera Iconica, `the true likeness'.) There is also a set of icons of the Virgin Mary that appear at this time said to have been painted by the evangelist Luke. Again the attribution is in order to give them status. What is important is that these images are not known before the sixth century and the stories of their origins must be treated as legendary.But the difference is that: 1) unlike "Greek myths" the Shroud does exist today; and 2) no one (including Freeman) would bother arguing whether "Greek myths" are authentic.And as for "The Abgar legends" which "claim that the image had come to Edessa in the first century where it had been hidden in the city wall before its `reappearance' in the sixth century" Freeman either is concealing from his readers, or may be simply ignorant of the fact, that many (if not most) Shroud pro-authenticists (including me) accept the modification to Ian Wilson's theory proposed by attorney/historian John J. (Jack) Markwardt that the Shroud was in Antioch from c. AD 47 until Antioch was devastated by a major earthquake in AD 526, after which the Shroud was taken to Edessa, and the Edessans retrospectively applied to their city, the true history of the Shroud at Antioch. However, see my "Problems of Markwardt's theory" and "My Ravenna theory" solution.

Briefly Markwardt's theory as set forth in his "The Fire and the Portrait" (1998); and "Antioch and the Shroud" (1999) [PDF]; and "Ancient Edessa and the Shroud" (2008) [PDF], proposes:

- The Shroud was first in the custody of the Apostle Peter in Jerusalem from c. AD 30-47, having been recovered by him when he and John entered Jesus' empty tomb, as recorded in Jn 20:3-8.

- Then following the persecution of the early Jewish Christians recorded in Acts 6:8-8:3, the Shroud was taken by St. Peter to Antioch, in ancient Syria. See Gal 2:11-12 where Peter was the leader of the church in Antioch, about AD 50.

- The Shroud was kept secret in and around Antioch from c. 47 to 357, most of that time in the control of minority Christian groups, the Arians and Monophysites, who kept the Shroud a closely guarded secret from iconoclastic Christians and Jews.

- In c. 357, following the Emperor Constantine's policy of centralising all passion relics in Constantinople, the Shroud was hidden in Antioch's city wall above the Gate of the Cherubim (the source of Edessa's similar legend) until it was rediscovered following the destruction of Antioch's city wall in a major earthquake in 526.

- Then, between 526 and the Persian further destruction of Antioch in 540, the Shroud was taken to Edessa, where it was regarded as a secondary relic to Edessa's letter of Jesus to Abgar V.

- During the Persian siege of Edessa in 544, following the failure of Jesus' letter to Abgar V protect the city, the Edessans took the Shroud into a tunnel under the Persian's wooden siege tower where they thrust a hot poker four times into the folded Shroud (the poker holes), the Persian siege tower miraculously caught fire, and the Persians abandoned their siege, sparing Edessa from Antioch's fate.

- The Edessans then regarded the Shroud as their primary relic, and to cover up the poker holes damage they doubled the Shroud in four and framed it, so that Jesus' face only appeared in landscape mode, becoming the Mandylion or Image of Edessa.

Markwardt's theory plausibly explains so many facts about the Shroud in its pre- and early-Eddessan period (c. AD 30-540) that it should be preferred over that part of Wilson's general theory.

Continued in part 7: "The Image of Edessa" (3)

Posted 23 August 2012. Updated 1 September 2025.