Here is part 10, "The Image of Edessa" (6), of my critique of historian Charles Freeman's, "The Turin Shroud and the Image of Edessa: A Misguided Journey," May 24, 2012 [page 8]. See previous part 9.

[Above (enlarge): "The Vignon markings-how Byzantine artists created a living likeness from the Shroud image. (1) Transverse streak across forehead, (2) three-sided `square' between brows, (3) V shape at bridge of nose, (4) second V within marking 2, (5) raised right eyebrow, (6) accentuated left cheek, (7) accentuated right cheek, (8) enlarged left nostril, (9) accentuated line between nose and upper lip, (10) heavy line under lower lip, (11) hairless area between lower lip and beard, (12) forked beard, (13) transverse line across throat, (14) heavily accentuated owlish eyes, (15) two strands of hair." (Wilson, I., "The Turin Shroud," 1978, p.82e).]

[Above (enlarge): "The Vignon markings-how Byzantine artists created a living likeness from the Shroud image. (1) Transverse streak across forehead, (2) three-sided `square' between brows, (3) V shape at bridge of nose, (4) second V within marking 2, (5) raised right eyebrow, (6) accentuated left cheek, (7) accentuated right cheek, (8) enlarged left nostril, (9) accentuated line between nose and upper lip, (10) heavy line under lower lip, (11) hairless area between lower lip and beard, (12) forked beard, (13) transverse line across throat, (14) heavily accentuated owlish eyes, (15) two strands of hair." (Wilson, I., "The Turin Shroud," 1978, p.82e).]

Freeman continues with his attempts to "poison the well" against historian Ian Wilson's theory that the Image of Edessa/Mandylion is the Shroud of Turin folded eight times (see my Tetradiplon and the Shroud of Turin) by the prejudicial "bizarre" and "enthusiasts":

An even more bizarre explanation comes when Wilson tackles Byzantine art. Seventy years ago a Frenchman, Paul Vignon, noted that the bearded face on the Turin Shroud has some of the characteristics of Byzantine art. All kinds of measuring was done and some enthusiasts found as many as sixty resemblances.

Again Freeman, "fails to tell his readers relevant material which might undermine his case, weak though it already is" (Freeman's own, hypocritical, pot calling the kettle black, criticism of Wilson in this paper). Paul Vignon was not merely "a Frenchman," but he was also a Professor of Biology and an artist. And they were not merely "some of the characteristics of Byzantine art" which Vignon discovered, but at least fifteen (15) unique markings on the Shroud (see above), which are all found (although no icon has all fifteen), on Byzantine depictions of Christ's face, from the 6th century onwards:

"This said, however, even from much this same early time there is actually one further even more compelling indicator that the Image of Edessa was one and the same as our Shroud. The seventh century saw another wave of Pantocrator-type depictions of Christ, which we have shown to be based on the Image of Edessa. One of these can be found in the little-visited St Ponziano catacomb in Rome's Transtevere district ... It is of exactly the same type as the Pantocrator icon at St Catherine's Monastery in Sinai that we earlier established as having been painted under the influence of the Image of Edessa. However, it features one highly important extra detail: on the forehead between the eyebrows there is a starkly geometrical shape resembling a topless square. Artistically it does not seem to make much sense. If it was intended to be a furrowed brow, it is depicted most unnaturally in comparison with the rest of the face. But if we look at the equivalent point on the Shroud face ... we find exactly the same feature, equally as geometric and equally as unnatural, probably just a flaw in the weave. The only possible deduction is that fourteen centuries ago an artist saw this feature on the cloth that he knew as the Image of Edessa and applied it to his Christ Pantocrator portrait of Jesus. In so doing he provided a tell-tale clue that the likeness of Jesus from which he was working was that on the cloth we today know as the Shroud. Seven decades ago Frenchman Paul Vignon identified another fourteen such oddities frequently occurring in Byzantine Christ portraits ... likewise seemingly deriving from the Shroud. Among these is a distinctive triangle immediately below the topless square. But like a Man Friday footprint of the Shroud's existence six centuries before the date given to it by carbon dating, the topless square alone is enough. (Wilson, I., "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," 2010, p.142).

[Above: Bust of Christ from the catacomb of St. Pontianus, Rome: Catacomba di Ponziano, Wikipedia, 31 January 2012. Note the Vignon marking on this 7-8th century mosaic, a three-sided `topless square' between the eyebrows (see below).]

As Wilson correctly points out, this Vignon marking no. 2, the three-sided `square' or `topless square', which is merely part of a flaw or change in the Shroud's weave (see below) was slavishly copied by Byzantine artists, from the 6th century onwards. And just as Robinson Crusoe's discovery of Man Friday's footprint on the seashore was conclusive proof that there was another human being on the island, so this topless square Vignon marking no. 2, which is on almost all (if not all) of the hundreds of Byzantine depictions of Christ's face since the 6th century, is alone conclusive proof that the Shroud existed as the Image of Edessa in at least the 6th century in the Byzantine world.

[Above (enlarge): ShroudScope "Face only Vertical" online Shroud photograph showing the three sided `square' or `topless square' Vignon Marking no. 2, superimposed on 7th-8th century bust of Christ from the catacomb of St. Pontianus, Rome: ShroudScope and Wikipedia.]

As the late evolutionary biologist Prof. Colin Patterson pointed out, copyright courts rule that it is "proof `beyond reasonable doubt'" of plagiarism if two or more works share the same error, and also that the original is the work in which the shared error is a physical flaw in the text:

"An interesting argument is that in the law courts (where proof `beyond reasonable doubt' is required), cases of plagiarism or breach of copyright will be settled in the plaintiff's favour if it can be shown that the text (or whatever) is supposed to have been copied contains errors present in the original. Similarly, in tracing the texts of ancient authors, the best evidence that two versions are copies one from another or from the same original is when both contain the same errors. A charming example is an intrusive colon within a phrase in two fourteenth-century texts of Euripides: one colon turned out to be a scrap of straw embedded in the paper, proving that the other text was a later copy." (Patterson, C., "Evolution," 1999, p.117).The `topless square' is a physical flaw or change in the weave of the fabric of the Shroud of Turin and so it has no intrinsic artistic

[Above: Closeup of face of the Man on the Shroud, showing that the `topless square' is part of a flaw or change in the Shroud's weave which runs all the way down the face (and in fact appears to run down the entire length) of the Shroud: ShroudScope "Durante 2002 Vertical"]

significance whatsoever. So those hundreds of Byzantine depictions of Christ's face from the 6th century onwards which have the `topless square' in exactly the same location it is on the Shroud, were copied from the Shroud, as the Image of Edessa. Just as a single human footprint in the sand, below the last high tide mark, proved to Robinson Crusoe beyond any reasonable doubt that he was no longer alone on his island, so the `topless square' alone (although there are 14 other Vignon markings) on hundreds of Byzantine icons since the 6th century is "proof `beyond reasonable doubt'" that the Image of Edessa is the Turin Shroud and so the latter already existed from at least the 6th century. Therefore, Freeman (and his ilk), who deny this "proof `beyond reasonable doubt'" of the authenticity of the Shroud based on the Vignon markings, are simply WRONG!

Freeman continues with his already failed quest to show that the Image of Edessa or Mandylion, is not the Shroud of Turin folded eight times, mounted on a board and framed so that only Christ's face was visible.

This is all interesting but Wilson goes on to make the absurd suggestion that this was because Byzantine art was born from the Image of Edessa, also known to Wilson as the Turin Shroud!This is another false "straw man" statement by Freeman, that Wilson claimed that "Byzantine art was born [in the sixth century] from the Image of Edessa." Wilson did not claim that there was no Byzantine art until the Image of Edessa (the Shroud of Turin "doubled in four") was rediscovered in the sixth century. In fact Wilson explicitly stated that there was Byzantine art before the sixth century. What Wilson actually stated was that Byzantine art underwent "a quite extraordinary change in how artists portrayed Jesus's likeness, which happened very soon after the Image of Edessa cloth came to light ... in the art of the sixth century there occurred a remarkable transformation in the way Jesus was depicted":

"But why should we believe that this Image of Edessa cloth was our Shroud? The main clue lies in a quite extraordinary change in how artists portrayed Jesus's likeness, which happened very soon after the Image of Edessa cloth came to light ... right up until at least the end of the fifth century the portrayals of Jesus lacked any authority, most representation depicting him beardless ... there was a general lack of any awareness of what he looked like. But in the art of the sixth century there occurred a remarkable transformation in the way Jesus was depicted. Just two of several surviving examples will serve to illustrate this. The first is a 'Christ Pantocrator' icon painted in encaustic - a wax technique, the recipe for which became lost after the eighth century - that is preserved in the remote monastery of St Catherine in the Sinai desert ... The second is a relief portrait of Christ on a silver vase that was found at Homs in Syria, and is now in the Louvre in Paris ... Firmly datable to the sixth century, both are authoritative, definitive versions of the distinctive likeness that today we instinctively recognize as Jesus Christ. And if we compare these front-facing likenesses with the face as visible on the Shroud before any discovery of the hidden photographic negative, there is a very uncanny resemblance: the same frontality, the same long hair, long nose, beard, etc. It is as if someone has studied the Shroud's facial imprint and for public consumption has very carefully crafted an interpretative official likeness from this in the guise of Christ Pantocrator - the 'King of All'." (Wilson, 2010, pp.133,135).So again, either Freeman has not actually read the above in Wilson's latest book as he implied he had (under a different subtitle) in this paper:

"Despite many years of research de Wesselow uncritically accepts much of the work of the veteran Shroud researcher Ian Wilson whose latest volume, The Shroud, Fresh Light on the 2000-year-old Mystery, Bantam Books, 2011, is used here."(which would be scholarly incompetence), or he has read the above, but is concealing it from his readers and in its place telling them something else which Wilson did not say (which would be scholarly dishonesty).

Freeman continues with his careless approach to historical accuracy:

Wilson makes some vague points about a new period in art at this time and finds a reference to two wandering Georgian monks with contacts with Edessa in the 530s who may have painted images.They were not "Georgian monks" but "Assyrian monks" who "travelled to Georgia specifically to paint interpretative versions of their charges [which included the Image of Edessa] for the newly founded churches there":

"Tradition in Georgia, the former republic of the old Soviet Union, has long held that some time around the mid 530s twelve Assyrian monks left Mesopotamia and travelled north to found several monasteries in Georgia. Present-day tour groups to Georgia can follow in these missionary monks' footsteps, and in Georgia's capital Tbilisi there is a very badly worn sixth-century Chris Pantocrator icon, the Anchiskhati - an almost exact counterpart to the one at St Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai - which is thought to have been brought to Georgia by this mission ...So again, for someone who claims to be a historian, albeit only a "freelance" one, who seems not to hold (or to have held) any university position, his current position being merely "head of history at St Clare's, Oxford" a boarding school:

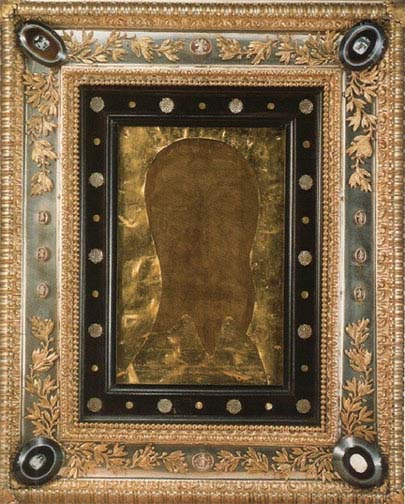

[Right ( (enlarge): "The Ancha Icon of the Savior, known in Georgia as Anchiskhati ... is a medieval Georgian encaustic icon, traditionally considered to be ... imprinted with the face of Jesus Christ miraculously transferred by contact with the Image of Edessa (Mandylion). Dated to the 6th-7th century ... The icon derives its name from the Georgian monastery of Ancha in what is now Turkey, whence it was brought to Tbilisi in 1664. The icon is now kept at the National Art Museum of Georgia in Tbilisi" ("Ancha Icon," Wikipedia, 20 August 2012. If you click on the image to enlarge it and then look closely, you will see that this "6th-7th century" icon, based on the Image of Edessa, also has (like many other Byzantine icons) the `topless square' Vignon marking no. 2, exactly where the Turin Shroud has the original, being part of a physical flaw or change in its weave (see above).]

The quite remarkable new insight from one of the recently discovered Georgian documents from Sinai is what it tells of the activities of two of these Assyrian monks, Theodosius from Edessa and Isidore from Edessa's sister city Hierapolis. Theodosius is specifically described as 'a deacon and monk [in charge] of the Image of Christ' in Edessa. As Georgian scholars recognize, this Image can be none other than our Image of Edessa, thereby confirming Evagrius's information that this was an extant historical object by this time, one evidently sufficiently important to have its own `carer'. Theodosius's companion Isidore was apparently responsible for a tile image belonging to Edessa's sister city Hierapolis. Both monks travelled to Georgia specifically to paint interpretative versions of their charges for the newly founded churches there. Never before have we been afforded a glimpse of who lay behind the rash of Christ portraits that appeared in the sixth century. It is quite evident from the Georgian document that they were Assyrian artist-monks from Edessa and its environs who saw themselves as missionaries or icon evangelists for the newly revealed 'divine likeness' that had been so recently rediscovered in Edessa." (Wilson, 2010, pp.135-136).

"Charles Freeman Charles Freeman is a scholar and freelance historian specializing in the history of ancient Greece and Rome. He is the author of numerous books on the ancient world including The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason. He has taught courses on ancient history in Cambridge's Adult Education program and is Historical Consultant to the Blue Guides. He also leads cultural study tours to Italy, Greece and Turkey. In 2003, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He lives in Suffolk, England. ... In addition to a law degree, he holds a master's degree in African history and politics from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London and an additional master's degree in applied research in education from the University of East Anglia. In 1978 he was appointed head of history at St Clare's, Oxford." ("Charles Freeman (historian) ," Wikipedia, 11 May 2012).Freeman is remarkably careless with historical facts, at least regarding the Shroud of Turin.

To be continued in part 11, "The Image of Edessa" (7). I never did continue this series, having bigger fish to fry than Freeman!

Posted 22 September 2012. Updated 2 September 2025.