FOURTEENTH CENTURY (1)

© Stephen E. Jones[1]

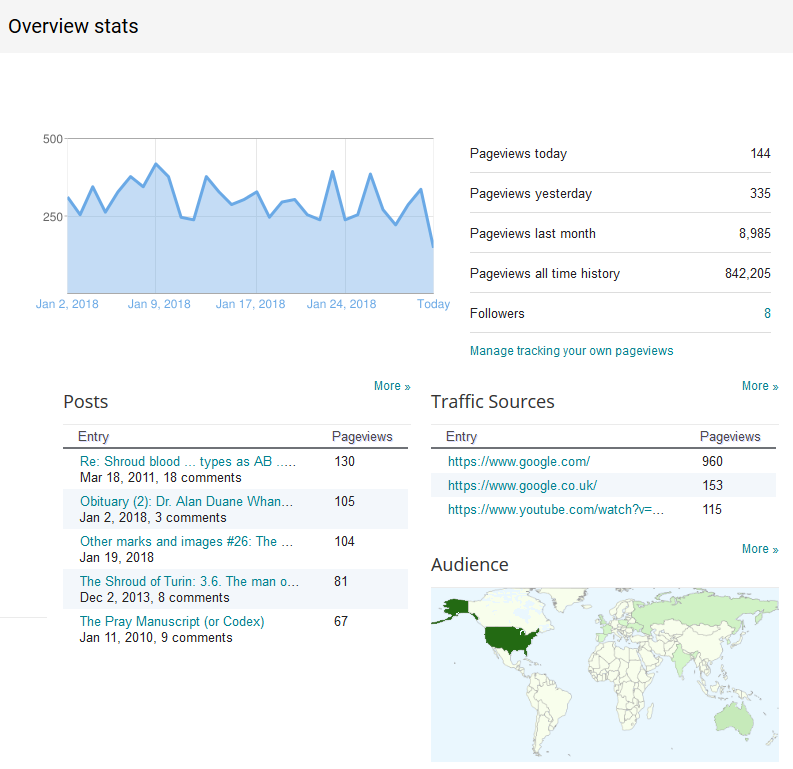

This is part #15, "Fourteenth century (1)" of my "Chronology of the Turin Shroud: AD 30 - present" series. I have decided to split this too-long post into two parts: (1) 1301-1350 and (2) 1351-1400. For more information about this series see part #1, "1st century and Index." Emphases are mine unless otherwise indicated.

[Index #1] [Previous: 13th century #14] [Next: 14th century (2) #16]

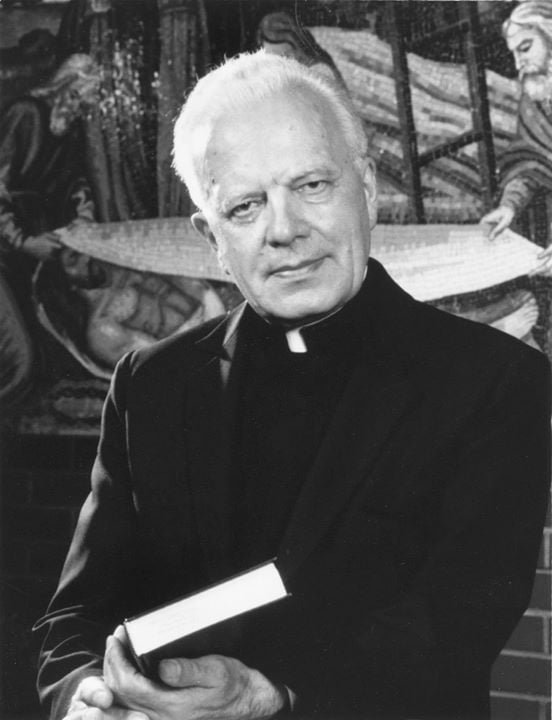

14th century (1) (1301-1350).[Above: Map of Lirey, France[2], showing the Church of St. Mary (centre above the `arms' of the Y intersection[3]), which was in 1516 built in stone over the the ruins of Geoffrey I de Charny's wooden church)[3a], in the grounds of which the Shroud of Turin was first exhibited in undisputed history in c.1355[3b] [see "c.1355"]. According to my theory (see below) Geoffroy I de Charny (c.1300–1356)'s request to King Philip VI of France (r.1328–1350) in early 1343 for funding to build and operate a church with five canons in this tiny village of Lirey indicated that Geoffroy already had, or had been promised by Philip, the Shroud to exhibit it there.]

c.1300 Birth of Geoffroy I de Charny (c.1300–1356) to Jean I de Charny de Mont-Saint-Jean (1263-1323) and Jeanne de Villurbain (1260-1310) in Burgundy, east-central France[4]. He was evidently the grand-nephew and namesake of the Templar Geoffroy de Charny (c.1240–1314)[5] who was burnt at the stake in 1314 [see "1314" below]. Geoffroy I was the first undisputed owner of the Shroud [see "c.1355"].

1307 Arrest at dawn on Friday, 13 October 1307 (a possible origin of the Friday the 13th superstition)[6] of the entire Knights Templar order in France, as ordered by King Philip IV of France (1268–1314)[7] [see "1119"] with the support of the first Avignon Pope, Clement V (c.1264–1314)[8]. The Templars were very wealthy[9] and Philip was deeply in debt to the order from financing his wars[10]. Following his arrest of the French Templars, Philip confiscated all their wealth[11]. Charges against the Templars included: idolatry - worshiping a head with a reddish beard[12], heresy[13], sorcery[14] and sodomy[15]. `Confessions' of guilt to these charges were extracted under torture[16].

1314 Among those arrested were Jacques de Molay (c.1243–1314), the Templars' Grand Master[17], and Geoffroy de Charny (c.1240–1314) the master of Normandy[18] (and grand-uncle of Geoffroy I de Charny - see above). They also were imprisoned and tortured[19] to extract their `confessions' to the false charges brought against them[20]. But at their trial they publicly retracted their, and their order's, `confessions'[21], so Philip IV ordered they be burned at the

[Right (enlarge. Depiction in the Chronicle of St Denis of the burning at the stake on 19 March 1314 of Templar leaders Jacques de Molay and Geoffroy de Charny, on the Île aux Juifs (Island of the Jews), in the Seine River, Paris[22].]

stake[23], on 19 March 1314, on the Île aux Juifs (Island of the Jews) in the Seine River, Paris[24]. From the stake de Molay cursed Philip and Clement and summoned them to meet him before the throne of God within the year to answer for their crimes, and both died during that very same year[25]! It was Ian Wilson's Templar ownership theory that Geoffroy I de Charny received the Shroud from Geoffroy de Charny the Templar[26]. But see "1119" and "1291" that Wilson no longer holds that theory.

[Left (enlarge): Example of the early fourteenth century Eastern Orthodox liturgical cloth known as an epitaphios, specifically symbolizing Jesus's burial Shroud, preserved in the Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Belgrade[31].]

Ian Wilson wrote of this epitaphios:

"... its inscription firmly dates it to the reign of Milutin II Uros, ruler of Serbia from 1282 to 1321, predating the 1350s when, according to Bishop d'Arcis (r. 1377–1395), the Shroud was `cunningly painted' [see "c.1355" and "1389"] seven hundred miles and several daunting mountains away in France. ... we see on it an image so strikingly reminiscent of the Shroud's front-of-body image that, whether directly or indirectly, it can hardly be other than that image's progeny .... We see the same long-haired, long-nosed, bearded face. We see the same crossed hands. ... the lance-wound correctly on the mirror- reverse side to that in which it appears on the Shroud ... And in the case of these same hands, although the thumbs are depicted, the way that the long fingers of the lower hand parallel those on the Shroud is particularly striking"[32].

c.1320 Birth of Jeanne de Vergy (c.1332–1428), the future second wife of Geoffroy I de Charny (above) [see "1346a" below]. Jeanne was a direct descendant of Othon IV de la Roche (c.1170-1234)[36] [see "c.1248"], who brought the Shroud from Constantinople["1204"] to Athens["1205a], from where he sent the Shroud to France["c.1206"]. So it was through Jeanne de Vergy at their marriage in c.1346 [see "1346a" below] that Geoffroy I de Charny became the owner of the Shroud.

1325 Mid-point of 1260-1390, i.e. 1325 ±65 [33], the claimed radiocarbon date of the Shroud[34] [see future "1989b"]. Some leading Shroud anti-authenticists claim that 1325 was the date of the Shroud[35].

c.1335 Marriage of Geoffroy I de Charny to Jeanne de Toucy (c.1301–c.1342)[37]. She was the daughter of Guy II de Toucy (–1308), Lord of Bazarne, Pierre-Perthuis and Vault-de-Lugny and of Guillemette de Beaumont-sur-Oise (-1308)[38]. The de Charnys and the de Toucy families were close to each other in Burgundy, no more than fifteen miles (~24 kms) apart[39]. Geoffroy had no lands of his own by family inheritance[40], but through this his first marriage he became Lord of Pierre-Perthuis[41]. They had no children[42] and Jeanne was dead by 1342[43].

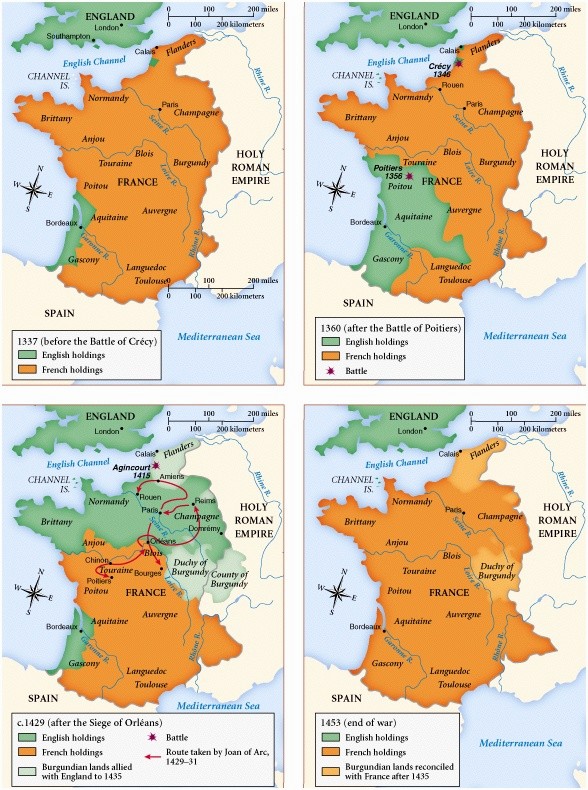

1337 Start of the Hundred Years' War[44], "a series of conflicts waged

[Above (enlarge)[45]: Territory controlled in the Hundred Years' War between England and France: 1337, 1360, c.1429 and 1453]

from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Plantagenet, rulers of the Kingdom of England, against the House of Valois, rulers of the Kingdom of France, over the succession to the French throne"[46].

1340a On 24 June 1340 in the Battle of Sluys, off today's Dutch city of Sluis[47], the English fleet under King Edward III (1312–1377) [my ancestor!] almost completely destroyed the French fleet[48]. Of the 213 French ships in the battle, the English captured 190, and the French dead totaled 16,000-18,000 including both French admirals[49].

1340b. Following Edward's heavy defeat of the French in the Battle of Sluys, on 23 July 1340 he besieged Tournai, which was in Flanders (today's Belgium), but loyal to King Philip VI of France (r.1328–1350)[50]. Geoffroy was sent by Philip VI to join the French garrison defending the town[51]. The defence was a victory for the French, when on 22 September 1340 with the French army drawing closer and Edward running out of money, a truce was brokered by Joan of Valois (c. 1294–1342), a sister of Philip VI and the mother-in-law of Edward III[52].

1341 In September 1341 [see "Battle of Champtoceaux" and "War of the Breton Succession"], Geoffroy fought in the defence of Angers, about 300 km (190 mi) southwest of Paris and the original seat of the Plantagenet dynasty[53] - Edward III's), alongside the Duke of Normandy, the son of Philip VI and future king John II (1319–1364)[54]. It is my theory that King Philip VI later (see "1343c" below) conferred the Shroud on Geoffroy I as a spoil of war ("conquis par feu" - see 16Feb15, 20Jun18 & 09Nov18), for protecting his son John II in this battle.

c. 1342 Death of Jeanne de Toucy, Geoffroy's childless first wife (see above)[55].

1342 On 30 September 1342 Geoffroy was taken prisoner in the Battle of Morlaix, Brittany[56]. He was taken to England by Sir Richard Talbot (c. 1305-1356), and kept in Talbot's principal residence of Goodrich Castle, Hertfordshire[57]. Geoffroy was then acquired as a prisoner by an English lord who had been the architect of the English victory in the battle at Morlaix, Sir William de Bohun (c. 1312–1360), Earl of Northampton[58]. Bohun allowed Geoffroy to return to France to raise his ransom[59] which was evidently soon paid because later that same year he was fighting the English at Vannes in Brittany[60].

c. 1343 According to my theory (see below), fears of an English invasion of Burgundy (which later happened-see above map "c.1429") led to the Shroud being secretly moved by the prominent[61] and pro-French de Vergys[62] from Besançon's St. Etienne's [Stephen's] Cathedral (which being in Franche-Comté was then part of the Holy Roman Empire[63]) to King Philip VI in Paris[64]. The plan, according to my theory was that Geoffroy would marry the legal owner of the Shroud, the then ~11 year-old Jeanne de Vergy (see above), when she reached the then marriageable age of 14.

Note that it is only my theory in respect of the timing of Geoffrey I receiving the Shroud from King Phillip VI and marrying Jeanne de Vergy. Specifically my theory takes account of Geoffroy I's seemingly extravagant request in early 1343 [see "1343c" below], in the midst of a war, for ongoing rent revenues to build and operate a church with five chaplains in the tiny village of Lirey, and Philip's swift granting of that request, indicating that Geoffroy already had, or had been promised by Philip, the Shroud to display it there. The theory that the Shroud reached Geoffroy I via Othon de la Roche, Besançon Cathedral and King Phillip VI (or Jeanne de Vergy direct) is probably held by the majority of Shroud pro-authenticists after the demise of all other theories of how Geoffrey I obtained the Shroud, including Wilson's Templar theory (see above). Those who hold that Geoffroy I obtained the Shroud from King Phillip VI (or Jeanne de Vergy direct), who received it from Besançon Cathedral, which received it from Othon de la Roche, include: Beecher[65], Barnes[66], O'Connell & Carty[67] and Scavone[68]

1343a In February 1343 the Truce of Malestroit (1343–1345) commenced[69].

1343b Geoffroy was promoted to the rank of chevalier (knight) by King Philip VI[70].

1343c Early in 1343, Geoffroy appealed to King Philip VI for rent revenues of 140 livres annually, so he could build and operate a chapel at Lirey with five chaplains (or canons)[71], for a village of only ~50 houses[72]. Evidently in early 1343 Geoffroy was already planning to exhibit the Shroud at that yet to be built Lirey church[73]! In which case Geoffroy I de Charny would already have the Shroud, or had received a promise from Philip VI that he would have it in the near future. Geoffroy's great-aunt Alix de Joinville (1256–1336) (who was also Bishop Pierre d'Arcis' [see above] great-aunt[74] - see "1355" and "1389e") evidently donated the lands and title of Lirey[75].

1343d In June 1343, Philip donated to chevalier Geoffroy 140 livres of rent revenue for ongoing financing of the Lirey church and its clergy[76].

1345a In May, during the truce in the war with England[77], Geoffroy set sail from Marseilles under the command of Humbert II, Dauphin of Vienne (1312–1355) [78], in a Crusade to recapture the Muslim-held citadel of the former Christian port of Smyrna ([Rev 1:1; 2:8)[79].

1345b End of the Truce of Malestroit in June 1345 (see above).

1346b Geoffroy missed the Battle of Crécy on 26 August 1346[82] in far northern France in which English forces under Edward III, aided by his sixteen-year-old son, Edward, Prince of Wales, aka the Black Prince (1330–1376)[83] decisively defeated a larger French army under Philip VI[84]. Geoffroy had been sent under the Duke of Normandy, the future King John II (r.1350–1364), to the southwest to blunt the campaign by the English in Gascony[85].

c.1347 Geoffrey I was first designated by King Phillip VI the Porte-oriflamme, bearer of the Oriflamme, France's sacred royal battle-standard[86] [Right (enlarge): A reconstruction of the Oriflamme[87].]. Recipients of the honour of bearing the Oriflamme, swore that they would die rather than lower it in battle[88]. The appointment was not for life, nor was it hereditary[89] and in fact Geoffroy I received the oriflamme four times: in 1347, 1351, 1355, and 1356[90].

bearer of the Oriflamme, France's sacred royal battle-standard[86] [Right (enlarge): A reconstruction of the Oriflamme[87].]. Recipients of the honour of bearing the Oriflamme, swore that they would die rather than lower it in battle[88]. The appointment was not for life, nor was it hereditary[89] and in fact Geoffroy I received the oriflamme four times: in 1347, 1351, 1355, and 1356[90].

1348a In January Geoffroy I was made a Councillor of King Philip VI[91].

1348b Geoffroy was sent to the northern city of Saint Omer, ~46 km (~28 miles) southeast of the English-held French port of Calais, as Governor, with all the military powers of the king[92].

1348c The Black Death began to devastate France, eventually killing one-third of the population[93], including in 1349 Philip VI's wife, Queen Joan of Burgundy (1293–1349)[94]. Joan was the daughter of Robert II, Duke of Burgundy (r. 1272-1306) and was "intelligent, strong-willed ... an able regent of France during the king's long military campaigns, was said to be the brains behind the throne and the real ruler of France"[95]. So it may well be that Queen Joan of Burgundy played a decisive, but unrecognised role in bringing the Shroud from Besançon in Burgundy to Philip VI in Paris and then to the Burgundians, Geoffroy I and Jeanne de Vergy!

1349a A document dated 3 January 1349 in the Lirey church archives, confirmed a donation by Philip VI of land yielding 140 livres annually that will pay the salaries and expenses of the canons[96] who will take charge of the Lirey church in which the Shroud will be exhibited[97].

1349b In March 1349 St. Etienne's Cathedral, Besançon, was struck by lightning[98]. The cathedral was badly damaged[99] and its records destroyed[100] by the resulting fire. It was discovered that the reliquary containing the Shroud was missing[101]. See "1349b" below and "1375" for the claimed finding of this lost Shroud.

1349c In April Geoffroy I wrote to Pope Clement VI (r. 1342-1352) advising of his intention to build a church at Lirey, to be staffed by five canons and a prebendary (Dean)[102] and requesting that the church be raised to the level of a collegiate[103]. Again (see above), this is evidence that Geoffroy already had the Shroud, and that both King Philip VI and the French Pope Clement VI knew it, since this number of clergy is far in excess of what tiny Lirey needed, as Wilson implies:

"At just fifty hearths, the village of Lirey at this time was of much the same tiny proportions as today ... [yet] The surprising aspect is its large clerical staff"[104].The Pope granted Geoffroy's request except for the church's collegiate status, because Geoffroy was subsequently captured by the English at Calais at the end of that year and taken a prisoner to London (see below)[105].

1349d On 31 December Geoffroy I was captured in a failed relief of the English held French port, Calais[106]. England's King Edward III who was in Calais, sent Geoffroy to England as a prisoner for a second time (see above)[107]. In the ~18 months of his captivity[108], Geoffroy wrote a book on chivalry, Le Livre de Chevalerie[109]. It contains veiled hints that Geoffroy was married: "Deeds undertaken for Love of a Lady"[110], even secretly: "... the most secret love is the most lasting and the truest ..."[111].

1350a First radiocarbon date of the Shroud as "1350 AD" at Arizona radiocarbon dating laboratory on 6 May 1988:

"The first sample run was OX1 [an oxalic acid standard]. Then followed one of the controls. Each run consisted of a 10 second measurement of the carbon-13 current and a 50 second measurement of the carbon-14 counts. This is repeated nine more times and an average carbon-14/carbon-13 ratio calculated. All this was under computer control and the calculations produced by the computer were displayed on a cathode ray screen ... everyone was waiting for the next sample-the Shroud of Turin! At 9:50 am 6 May 1988, Arizona time, the first of the ten measurements appeared on the screen. .... At the end of that one minute we knew the age of the Turin Shroud! The next nine numbers confirmed the first. It had taken me eleven years to arrange for a measurement that took only ten minutes to accomplish! Based on these 10 one minute runs, with the calibration correction applied, the year the flax had been harvested that formed its linen threads was 1350 AD-the shroud was only 640 years old! ... I remember Donahue saying that he did not care what results the other two laboratories got, this was the shroud's age"[112].Note: 1) The AMS radiocarbon dating process was fully computerised: "All this was under computer control and the calculations produced by the computer were displayed. Therefore the dating of the Shroud was vulnerable to computer hacking without the other laboratory staff being aware of it. See my "The 1260-1390 radiocarbon date of the Turin Shroud was the result of a computer hacking" series. 2) The owner of the Shroud in 1350, Geoffroy I de Charny, was then a prisoner of war in England! 3) After only one dating run, at only one laboratory, all present gullibility and unscientifically accepted "this was the shroud's age" without even considering that in 1350 France was in the middle of a war and one-third of its population was being killed by the Black Death, yet Geoffroy I de Charny, the author of a book on knightly ethics, was allegedly involved in a forgery of Jesus' burial shroud!

1350b Death of King Philip VI on 22 August 1350[113]. He was succeeded by his son King John II (r.1350–1364)[114].

Continued in the next part #16 of this series.

Notes

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to quote from any part of this post (but not the whole post), provided it includes a reference citing my name, its subject heading, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

2. Extract from Google Maps (Earth) Classic View, search on Lirey, France, 11 January 2014. [return]

3. Verified by Google StreetView and by comparison with Jang, A.W., 2013, "Introducing... Lirey, France!," Shroud Center of Southern California. [return]

3a. [return]

3b. Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London, pp.221-222. [return]

4. Currer-Briggs, N., 1995, "Shroud Mafia: The Creation of a Relic?," Book Guild: Sussex UK, p.221; Jones, S.E., 2015, "de Charny Family Tree," Ancestry.com.au (members only). [return]

5. Jones, 2015, "de Charny Family Tree," Ancestry.com.au. See Brent, P. & Rolfe, D., 1978, "The Silent Witness: The Mysteries of the Turin Shroud Revealed," Futura Publications: London, p.17; Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition, p.317; Morgan, R., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia, p.41; Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY, p.97; Antonacci, 2000, p.148; Scavone, D.C., "The History of the Turin Shroud to the 14th C.," in Berard, A., ed., 1991, "History, Science, Theology and the Shroud," Symposium Proceedings, St. Louis Missouri, June 22-23, 1991, The Man in the Shroud Committee of Amarillo, Texas: Amarillo TX, pp.171-204, 197; Borkan, M., 1995, "Ecce Homo?: Science and the Authenticity of the Turin Shroud," Vertices, Duke University, Vol. X, No. 2, Winter, pp.18-51, 35; Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.115; Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY, p.149. [return]

6. Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK, p.96. [return]

7. Morgan, 1980, p.40; Maher, 1986, p.96; Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY, p.274; Antonacci, 2000, p.148; Wilson, 2010, p.302; Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition, p.33; "Knights Templar: Arrests, charges and dissolution," Wikipedia, 12 February 2018; Oxley, 2010, p.96. [return]

8. Wilson, 1979, p.208; Scavone, 1991, p.197; Maher, 1986, pp.95-96; Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, p.9. [return]

9. Maher, 1986, pp.94,96; Antonacci, 2000, p.148; Tribbe, 2006, p.33. [return]

10. "Knights Templar," Wikipedia, 12 February 2018. [return]

11. Wilson, I., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London, pp.117-118; Wilcox, R.K., 2010, "The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery," [1977], Regnery: Washington DC, p.111; Fanti, G. & Malfi, P., 2015, "The Shroud of Turin: First Century after Christ!," Pan Stanford: Singapore, p.58. [return]

12. Scavone, 1991, p.197; Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.201; Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London, p.117; Wilson, 2010, p.302. [return]

13. Maher, 1986, p.95; Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.201; Oxley, 2010, p.96. [return]

14. Oxley, 2010, p.96. [return]

15. Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.201; Oxley, 2010, p.96; Wilson, 2010, p.302. [return]

16. Wilson, 1979, p.190; Maher, 1986, pp.95-96; Antonacci, 2000, p.148; Tribbe, 2006, p.33; Oxley, 2010, p.96. [return]

17. Brent & Rolfe, 1978, p.17; Borkan, 1995, p.35; Antonacci, 2000, p.148; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.117. [return]

18. Brent & Rolfe, 1978, p.17; Borkan, 1995, p.35; Scavone, 1991, p.197; Wilson, 1998, p.274; Antonacci, 2000, p.148; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.117. [return]

19. Wilson, 1979, p.317; Antonacci, 2000, p.148. [return]

20. Wilson, 1979, p.317; Antonacci, 2000, p.148. [return]

21. Wilson, 1979, p.317; Maher, 1986, p.97; Oxley, 2010, p.97. [return]

22. "Jacques de Molay," Wikipedia, 5 February 2018. [return]

23. Scavone, 1991, p.197; Wilson, 1998, p.136; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.117. [return]

24. Wilson, 1979, pp.190-191; Guerrera, 2001, p.9; Wilson, 2010, p.302. [return]

25. Oxley, 2010, p.97. [return]

26. Scavone, 1991, p.197. [return]

27. Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London, p.150; Wilson, 1998, p.274. [return]

28. Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY, p.154. [return]

29. Iannone, 1998, p.154. [return]

30. Iannone, 1998, p.154. [return]

31. Wilson, 2010, p.274C. [return]

32. Wilson, 1998, p.137. [return]

33. Wilson, 1998, p.7; McCrone, W.C., 1999, "Judgment Day for the Shroud of Turin," Prometheus Books: Amherst NY, pp.1, 141, 178, 246; Tribbe, 2006, p.169; Oxley, 2010, p.87; de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London, p.170. [return]

34. Damon, P.E., et al., 1989, "Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin," Nature, Vol. 337, 16 February, pp.611-615, 611. [return]

35. Gove, H.E., 1996, "Relic, Icon or Hoax?: Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud," Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol UK, pp.293, 300; McCrone, 1999, pp.xxiii, xx. [return]

36. Currer-Briggs, N., 1988a, "The Shroud and the Grail: A Modern Quest for the True Grail," St. Martin's Press: New York NY, p.38-39; Scavone, D.C., 1989, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA, p.100; Scavone, 1991, p.199; Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.214; Guerrera, 2001, p.12; Kaeuper, R.W., 2005, "Introduction" to de Charny, G., "A Knight's Own Book of Chivalry," [c. 1350], Kennedy, E., transl., The Middle Ages Series, University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia PA, p.4; Tribbe, 2006, pp.33, 44, 194-195, 230; Piana, A., 2007, "The Shroud's "Missing Years," British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, No. 66, December, pp.9-25,28-31; Oxley, 2010, pp.105-106; Wilson, 2010, pp.210-211, 213. [return]

37. Jones, 2015, "de Charny Family Tree," Ancestry.com.au. See Wilson, 1979, p.89; Currer-Briggs, N., 1988b, "The Shroud in Greece," British Society for the Turin Shroud Monograph no. 1, pp.1-16, 8, 10; Wilson, 2010, p.214. [return]

38. Jones, 2015, "de Charny Family Tree," Ancestry.com.au. [return]

39. Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.213; Wilson, 2010, p.214. [return]

40. Wilson, 1979, p.89 [return]

41. Wilson, 1979, p.89; Kaeuper, 2005, p.4. [return]

42. Kaeuper, 2005, p.4. [return]

43. Kaeuper, 2005, p.4. [return]

44. Wilson, 1998, pp.130, 275; Tribbe, 2006, p.38; Oxley, 2010, p.46; Wilson, 2010, p.214. [return]

45. "The Hundred Years' War vs. The Eastern Front of World War II - A Good Comparison?," Historum, 6 July 2015. [return]

46. "Hundred Years' War," Wikipedia, 15 February 2018. [return]

47. "Sluis," Wikipedia, 12 November 2017. [return]

48. "Battle of Sluys," Wikipedia, 22 October 2017. [return]

49. Oxley, 2010, p.47. [return]

50. "Siege of Tournai (1340)," Wikipedia, 20 August 2017. [return]

51. Wilson, 1998, pp.130, 275; Kaeuper, 2005, p.4; Oxley, 2010, p.46; Wilson, 2010, p.214. [return]

52. "Siege of Tournai (1340)," Wikipedia, 20 August 2017. [return]

53. "Angers," Wikipedia, 6 February 2018. [return]

54. Wilson, 1998, p.275; Oxley, 2010, p.46; Wilson, 2010, p.214. [return]

55. Kaeuper, 2005, p.4. [return]

56. Wilson, 1998, p.275; Kaeuper, 2005, p.5. [return]

57. Kaeuper, 2005, p.5. [return]

58. Kaeuper, 2005, p.5; "William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton: Campaigns in Flanders, Brittany, Scotland, Victor at Sluys and Crecy," Wikipedia, 30 November 2017. [return]

59. Wilson, 1998, p.275; Kaeuper, 2005, p.5. [return]

60. Wilson, 1998, p.275; Kaeuper, 2005, p.5. [return]

61. Scavone, 1989, p.100. [return]

62. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.50; Scavone, D.C., 1998, "A Hundred Years of Historical Studies on the Turin Shroud," Paper presented at the Third International Congress on the Shroud of Turin, 6 June 1998, Turin, Italy, in Minor, M., Adler, A.D. & Piczek, I., eds., 2002, "The Shroud of Turin: Unraveling the Mystery: Proceedings of the 1998 Dallas Symposium," Alexander Books: Alexander NC, pp.58-70, 67. [return]

63. Scavone, D.C., "The Turin Shroud from 1200 to 1400," in Cherf, W.J., ed., 1993, "Alpha to Omega: Studies in Honor of George John Szemler," Ares Publishers: Chicago IL, pp.187-225, 207. [return]

64. Scavone, 1998, p.67. [return]

65. Beecher, P.A., 1928, "The Holy Shroud: Reply to the Rev. Herbert Thurston, S.J.," M.H. Gill & Son: Dublin, pp.54-67. [return]

66. Barnes, A.S., 1934, "The Holy Shroud of Turin," Burns Oates & Washbourne: London, pp.54-55. [return]

67. O'Connell, P. & Carty, C., 1974, "The Holy Shroud a41ur Visions," TAN: Rockford IL, pp.8-9. [return]

68. Scavone, 1989, pp.96-101; Scavone, 1991, pp.198-200; Scavone, 1993, pp.187-213; Scavone, 1998, p.66-67. [return]

69. "Hundred Years' War (1337–1360): Truce of Malestroit (1343–1345)," Wikipedia, 7 January 2018. [return]

70. Wilson, 1998, p.275; Kaeuper, 2005, p.5. [return]

71. Crispino, D.C., 1981, "Why Did Geoffroy de Charny Change His Mind?," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 1, December, pp.28-34, 30; Tribbe, 2006, p.41. [return]

72. Crispino, 1981, pp.29-30. [return]

73. Tribbe, 2006, p.41. [return]

74. Crispino, D.C., 1990, "Kindred Questions," Shroud Spectrum International, #34, March, pp.43-44. [return]

75. Crispino, 1981, p.30. [return]

76. Crispino, 1981, p.30; Wilson, 1998, p.274. [return]

77. Wilson, I., 1992, "Reviews," BSTS Newsletter, No. 32, September, pp.15-18, 16. [return]

78. Wilson, 1998, p.275; Kaeuper, 2005, p.6. [return]

79. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.48; Oxley, 2010, p.47. [return]

80. Wilson, 1998, p.132. [return]

81. "Marriageable age: Middle Ages," Wikipedia, 21 February 2018. [return]

82. Kaeuper, 2005, p.6. [return]

83. Heller, J.H., 1983, "Report on the Shroud of Turin," Houghton Mifflin Co: Boston MA, pp.18; Wilson, 2010, p.224. [return]

84. "Battle of Crécy," Wikipedia, 28 January 2018; Oxley, 2010, p.44. [return]

85. Kaeuper, 2005, p.6. [return]

86. Wilson, 1998, p.276; "Oriflamme: Porte oriflamme," Wikipedia, 2 January 2018. [return]

87. "File:Oriflamme.svg," Wikimedia Commons, 5 February 2015. [return]

88. Wilson, 1998, p.276; Wilson, 2010, pp.223-224. [return]

89. Crispino, D.C., 1989, "Geoffroy de Charny's Second Funeral: Part II," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 32/33, September/December, pp.38-42, 42. [return]

90. Tribbe, 2006, p.231. [return]

91. Wilson, 1998, p.276. [return]

92. Crispino, D.C., 1989, "Geoffroy de Charny's Second Funeral," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 30, March, pp.9-13, 11; Wilson, 1998, p.275; Wilson, 2010, p.217. [return]

93. McNair, P., "The Shroud and History: Fantasy, Fake or Fact?," in Jennings, P., ed., 1978, "Face to Face with the Turin Shroud ," Mayhew-McCrimmon: Great Wakering UK, p.33; "Black Death: Death toll," Wikipedia, 19 February 2018. [return]

94. "Joan the Lame: Queenship," Wikipedia, 11 February 2018. [return]

95. "Philip VI of France: Marriages and children," Wikipedia, 29 January 2018. [return]

96. Crispino, 1981, p.30; Crispino, D.C., 1987, "Geoffroy de Charny in Paris," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 24, September, pp.13-18, 18. [return]

97. Wilson, 1998, p.276. [return]

98. Beecher, 1928, p.60; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.50; Scavone, 1993, p.205; Tribbe, 2006, p.194. [return]

99. Scavone, 1989, p.98. [return]

100. Scavone, 1991, p.199; Scavone, 1993, p.193. [return]

101. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.50; Scavone, 1991, p.199. [return]

102. Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.30; Wilson, 1998, p.276; Tribbe, 2006, p.41. [return]

103. Crispino, 1981, p.30; Tribbe, 2006, p.41. [return]

104. Wilson, 2010, pp.219-220. [return]

105. Crispino, 1981, p.30; Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.30; Wilson, 1998, p.276; Tribbe, 2006, p.41. [return]

106. Wilson, 1979, p.196; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.48; Wilson, 1998, p.277; Tribbe, 2006, p.231; Oxley, 2010, p.44. [return]

107. Wilson, 1998, p.277; Guerrera, 2001, p.10; Oxley, 2010, p.44. [return]

108. Wilson, 1979, p.196; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.48. [return]

109. Oxley, 2010, p.45. [return]

110. Kaeuper, 2005, pp.52-53 [return]

111. Kaeuper, 2005, p.65. [return]

112. Gove, H.E., 1996, "Relic, Icon or Hoax?: Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud," Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol UK, p.264. [return]

113. Wilson, 1998, p.277. [return]

114. Wilson, 1998, p.277. [return]

Posted 10 February 2018. Updated 14 November 2025.