Philip E. Dayvault's 2016 book,  "The Keramion, Lost and Found: A Journey to the Face of God" [Right: Amazon.com[1].] arrived by mail on 15th April, 2016. Here is my review of it, between the horizontal lines, on which will be the basis of a reader's review that I will submit to Amazon.com. [However, as mentioned in my 10Jul16, I belatedly discovered that, "The ideal length is 75 to 500 words" for an Amazon.com customer review, and this review was already many times that, so I abandoned that Amazon.com review]. I hope this review will be found by some intending buyers of the book before they waste their money on it (unless they are into historical fiction, or rather fantasy). See my previous posts, "`Modern-day 'Indiana Jones' links Shroud to 1st century': Shroud of Turin News - March 2016" and "`Phil Dayvault Presents Major New Evidence from Early Christianity': Shroud of Turin News - February 2016." Dayvault's words are in bold and the numbers in square brackets are page numbers in the book.

"The Keramion, Lost and Found: A Journey to the Face of God" [Right: Amazon.com[1].] arrived by mail on 15th April, 2016. Here is my review of it, between the horizontal lines, on which will be the basis of a reader's review that I will submit to Amazon.com. [However, as mentioned in my 10Jul16, I belatedly discovered that, "The ideal length is 75 to 500 words" for an Amazon.com customer review, and this review was already many times that, so I abandoned that Amazon.com review]. I hope this review will be found by some intending buyers of the book before they waste their money on it (unless they are into historical fiction, or rather fantasy). See my previous posts, "`Modern-day 'Indiana Jones' links Shroud to 1st century': Shroud of Turin News - March 2016" and "`Phil Dayvault Presents Major New Evidence from Early Christianity': Shroud of Turin News - February 2016." Dayvault's words are in bold and the numbers in square brackets are page numbers in the book.

Leading Shroud scholar, Ian Wilson once began a review of a much better book than this one by Philip E. Dayvault, with:

"... very sadly the subject of the Shroud needs this particular book like a hole in the head ..."[2]And very sadly the same applies to Dayvault's book because it is so wrong that it is at best an exercise in self-delusion (as will be seen). And I write as a fellow Christian and Shroud pro-authenticist of Dayvault.

• "Upon seeing the cloth, King Abgar V was healed of leprosy and gout and converted to Christianity, as soon did the entire city." [viii]. Wrong. While Edessa's King Abgar V (r.13-50) may have been healed of leprosy by Jesus' disciple Thaddeus and then converted to Christianity, along with some of Edessa's citizens, there is no good evidence for, and much evidence against, that Abgar V saw "the cloth," i.e. the Mandylion, which was the Shroud four-doubled (tetradiplon), i.e. folded 4 x2 = 8 times[3]. In the earliest c. 325 record of Abgar V's healing and conversion, that of Eusebius (c. 260–340)[4], there is no mention of a cloth[5] or an image[6]. And some (if not most) leading Shroud scholars now regard the story of Abgar V "seeing the cloth" as a "pious fraud"[7] and accept that it was under King Abgar VIII (r. 177-212) that Edessa became a Christian city[8]. Shroud pro-authenticist historian Dan Scavone has shown that it was Abgar VIII who was the originator of the Abgar V legend and had it inserted into Edessa's royal archives[9] (unknown to Eusebius). Even Ian Wilson the leading proponent of the Abgar V theory, now concedes:

"Abgar V was part of a dynasty of rulers bearing this same name, and one successor slightly more favoured by historians as the Abgar whom Addai [Thaddeus] converted (and who therefore may have been the true recipient of the Image of Edessa/Shroud) is Abgar VIII,' who reigned from 179 [sic] to 212" (my emphasis)[10]

• "Also, according to the legend, King Abgar V displayed the cloth and had a tile bearing the same facial image of Jesus Christ placed over a Western Gate of the `City'" ... [viii]. Wrong. The 945 "Official History of the Image of Edessa" (Narratio de Imagine Edessena)[11], which is Appendix C, pages 272-290, in Ian Wilson's 1979 book, The Shroud of Turin): 1) does not say "a tile bearing the same facial image of Jesus Christ" was "placed over a Western Gate of the `City'." That "tile" (there were two) which the Official History states, had a "copy of the likeness of the divine face" which "had been transferred to the tile from the cloth" was at "Hierapolis" [Hierapolis, Syria, modern Manbij], not Edessa:

"8. Christ entrusted this letter to Ananias, and knew that the man was anxious to bring to completion the other command of his master, that he should take a likeness of Jesus' face to Abgar. The Savior then washed his face in water, wiped off the moisture that was left on the towel that was given to him, and in some divine and inexpressible manner had his own likeness impressed on it. This towel he gave to Ananias and instructed him to hand it over to Abgar ... When he was returning with these things, Ananias then hurried to the town of Hierapolis ... He lodged outside this city at a place where a heap of tiles which had been recently prepared was lying, and here Ananias hid that sacred piece of cloth. ... The Hieropolitans ... found ... [on] one of the tiles nearby, another copy of the likeness of the divine face ... the divine image had been transferred to the tile from the cloth ... they retained the tile on which the divine image had been stamped, as a sacred and highly valued treasure" (my emphasis)[12].That tile with Jesus' image on it was transferred from Hierapolis, Syria, to Constantinople in 968/969[13], that is ~24/25 years after the Mandylion/Shroud had been transferred from Edessa to Constantinople in 944[14].Nor does the Official History say that the Edessa tile was "placed over" a gate of the city. It states that the "the image," i.e. the image of Jesus on the "towel" (see above), "lay" in a "place" which "had the appearance of a semispherical cylinder" and "a tile," of which nothing is said about it having an image, was "placed ... on top" of the image:

"15. ... A statue of one of the notable Greek gods has been erected before the public gate of the city by the ancient citizens and settlers of Edessa to which everyone wishing to enter the city had to offer worship and customary prayers. Only then could he enter into the roads and streets of the city. Abgar then destroyed this statue and consigned it to oblivion, and in its place set up this likeness of our Lord Jesus Christ not made by hand, fastening it to a board and embellishing it with the gold which is now to be seen ... And he laid down that everyone who intended to come through that gate, should-in place of that former worthless and useless statue-pay fitting reverence and due worship and honor to the very wondrous miracle-working image of Christ, and only then enter the city of Edessa. And such a monument to and offering of his piety was preserved as long as Abgar [V] and his son [Ma'nu V] were alive, his son succeeding to his father's kingdom and his piety. But their son and grandson [Ma'nu VI] succeeded to his father's and grandfather's kingdom but did not inherit their piety ... Therefore ... he wished just as his grandfather had consigned that idolatrous statue to oblivion so he would bring the same condemnation on the image of the Lord also. But this treacherous move was balked of his prey. For the bishop of the region, perceiving this beforehand, showed as much forethought as possible, and, since the place where the image lay had the appearance of a semispherical cylinder, he lit a lamp in front of the image, and placed a tile on top. Then he blocked the approach from the outside with mortar and baked bricks and reduced the wall to a level in appearance. And because the hated image was not seen, this impious man desisted from his attempt. .. Then a long interval of time elapsed and the erection of this sacred image and its concealment both disappeared from men's memories" (my emphasis)[15]And Wilson pointed out that "a semispherical cylinder" is an apt description of "an arched vault," and "one of the four main gates of Edessa, that to the west, was specifically known in Syriac as the Kappe gate, which means gate of arches or vaults"[16]. So there is no reason to think that this undistinguished, "a tile," placed on top of the Mandylion/Shroud, in an arched vault above Edessa's "public gate of the city" (see above) the Western Gate, was: a) attached to anything; and b) had an image on it. The only tile which the 945 Official History records as having an image on it was the tile which had been in "a heap of tiles" at Hierapolis Sysria, and was still there in 945 when the Official History was written. So this Hierapolis tile, the only tile which is recorded as having an image of Jesus on it, must have been the tile which was later called "the Keramion." And that Hierapolis tile had never been at Edessa nor had anything to do with Edessa! So the answer to Dayvault's question that he asked in the Preface of his book:

"Could the small mosaic, the ISA Tile, be the actual historical and legendary Keramion?"[viii]already is a resounding NO, and we are still only in the Preface, with still more to come in that Preface!

"... (Citadel), as a memorial to this momentous event. "[viii]. Wrong. As per my previous post, firstly, the Citadel was not the city, but a castle inside the city of Edessa[17] (see photo below). Secondly,

[Above (enlarge): Photo at page 221 of Dayvault's book of Edessa's citadel, with Dayvault's self-evidently false annotation that at the arrowed point is a "Gate" when there is no gate (see further below). But note that even Dayvault has to admit that this is only the Western end of "the Citadel" not of the city!]

[Above (enlarge): Photo at page 221 of Dayvault's book of Edessa's citadel, with Dayvault's self-evidently false annotation that at the arrowed point is a "Gate" when there is no gate (see further below). But note that even Dayvault has to admit that this is only the Western end of "the Citadel" not of the city!]

the Citadel (which Dayvault on page 60 agrees was called the "Birtha") did not exist in the time of Abgar V (r.13-50) but was built by Abgar VIII (r. 177-212) in 205: "The sixth-century Syriac Chronicle of Edessa announces that `in the year 205 Abgar VIII built the Birtha."[18]. Thirdly, Dayvault is misleading his readers by a fallacious word-play between "city" and "citadel." In his online PDF, Dayvault wrote:

"Interestingly, the word, `city' derives from the Latin word, `civitas', which also can mean `citadel.'"[19]The footnote 7 Dayvault cited, "7 http://viagabina rice.edu/oecus/oecus html, `Site 10 Villa: The Oecus Emblema', by Philip Oliver-Smith," does not have the words "civitas" or "citadel" in it. And in his book Dayvault simply asserts, with no reference:

"Civitas (Latin) means either city or citadel"[117].But apart from that being false (my Latin-English dictionary states that the Latin "civitas" means "citizenship; community state;" and that the English "citadel" is "arx" in Latin[20]), that word-play only works in English. In Syriac the word for "citadel" is birtha[21], which Dayvault in his book even states[60] and "Edessa" in Syriac is "Orhay"[22].

And as can be seen in the photo below from page 220 of Dayvault's book, with his annotation that this is the "Western Gate of the Citadel," on that same page 220 Dayvault wrote that it was "Viewed

[Above (enlarge): Photo at page 220 of Dayvault's book of the Western end of the Citadel, with his self-evidently false (and deluded) annotation that it is the "Western Gate of the Citadel. But as can be seen in the maximum zoom Google Earth photo of the Western end of the Citadel, again there is no gate!]

from across the moat while looking eastward, the westernmost tip of the Citadel in Sanliurfa and its tunnel entrance is pictured above." As can be seen in the Google Earth photo below, that place from where

[Above (enlarge): Google Earth photo of Sanliurfa[23] showing the Western end of Edessa's Citadel. The triangular `island' (red arrow) is evidently from where Dayvault took his photo above, and the circular structure (blue arrow) is evidently what he called the "Western Gate Monument." Which is in fact the ruins of a tower/windmill (see below)!]

Dayvault evidently took his page 220 photo above, is on the triangular `island' to the upper left of the western end of the Citadel (red arrow). And the circular structure on the tip of the western end of the Citadel blue arrow) is evidently what Dayvault called the "Western Gate Monument" in his same photo above. But a photo on a "Rome Art Lover's" website identified this as the remains of a tower/windmill (see below). That is confirmed by an online tourist guide document,

[Above (enlarge): "Remains of a windmill tower at the western end of the citadel ..."[24]. See below that this windmill tower is "Byzantine and Islamic," which is 11th-12th century. How could Dayvault go to Sanliurfa, with a Turkish guide/interpreter (page 95ff), and not know that this is the remains of a windmill tower? And that it is 11th-12th century?]

"A Guide to Southeastern Anatolia," which states of "Sanliurfa": "The ruined Byzantine and Islamic structures include a windmill to the west of the citadel" (my emphasis)[25]. Note that this ruined windmill tower is "Byzantine and Islamic," but the Byzantine period in Edessa was from 1031[26] and ended with the Islamic conquest of Edessa in 1144[27]! So this windmill tower dates from between the 11th and 12th centuries, which is about a thousand years too late to be the "public gate of the city" (above) which, according to the 945 Official History (above), the Mandylion/Shroud, tile and lamp had been hidden! And therefore about a thousand years too late to be Dayvault's "Western Gate Entrance" (see below). Indeed by 1031 the Shroud and Keramion had been in Constantinople for ~87 and ~63 years respectively!

That this is the same structure which Dayvault called the "Western Gate Monument" above, but from a different angle, is confirmed by its inclusion in a triptych photo on page 222 of his book from that different angle (see below).

[Above (enlarge): Triptych photo on page 222 of Dayvault's book, being different views of what he calls, the "Western Gate Monument." The middle photo especially shows that it is in fact the windmill tower ruins in the photo above!]

Thus, all visitors to Edessa would see it and pay homage to the one true God." [viii]. Wrong. First, the Official History does not say that "all visitors to Edessa would see it" the tile "and pay homage to the one true God." It says (see above), that "everyone who intended to come through that gate ["the public gate of the city"], should ... pay fitting reverence and due worship and honor to the very wondrous miracle-working image of Christ" which "fasten[ed] ... to a board and embellish[ed] .. with ... gold," that is, the Mandylion/Shroud. As we saw above, the "tile" at Edessa had no image and its only function was to be "on top" of the Mandylion/Shroud. Why does Dayvault even want to boost this mere plain tile to the detriment of the Shroud?

Second, Dayvault (deludedly), claims that the "tunnel" in these windmill tower (see below) was "the public gate of the city" (see above)

[Above (enlarge): Photo on page 226 of Dayvault's book of the tunnel in this 11th-12th century (see above) windmill tower ruins, which Dayvault (deludedly) calls, "The Western Gate Entrance."]

within which the Mandylion/Shroud, the tile and lamp had supposedly been hidden! So incredible is this that I myself did not realise that is what Dayvault had been claiming. At page 228, Dayvault claims (or implies) that the Edessa tile was on a "single marble block" which had been in a cavity (see below) about "2 feet high by 3.5 feet wide" by "8-12 inches" deep (about 61 cms H x 107 cms W x 25 cms D):

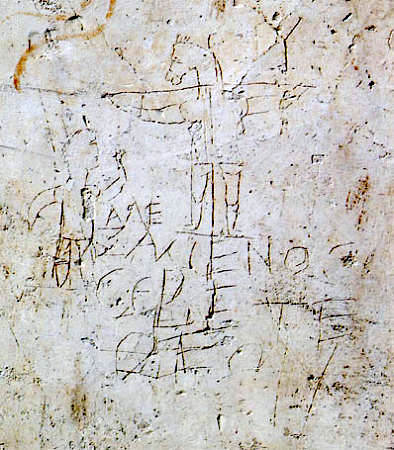

"The opening above the Western Gate tunnel entrance measures approximately 2 feet high by 3.5 feet wide. The depth of the opening is approximately 8-12 inches. A single marble block is missing from the cavity. A block, similar in type to adjacent blocks, that would have been suitable for the accommodation of the ISA Tile with nimbus lies directly at the entrance to the tunnel."[228]The cavity over the top of the tunnel (above) is where Dayvault claims (see future below) that the marble block on which the Sanliurfa mosaic, which he claims was the Keramion, was attached. This would have been the place in his book where Dayvault should have produced his key evidence that one of the loose blocks nearby matched the underside of the Sanliurfa mosaic, which Dayvault had claimed in his PDF, accompanied by a comparison photo (below), that he had "forensically

[Above (enlarge): Dayvault's claimed "unique features" of a stone block at what he calls the "Western Gate" of Edessa's Citadel and the underside of the Sanliurfa mosaic[28]. See my previous post where I pointed out that none of Dayvault's claimed "unique features" between the stone block and mosaic tile, match!]

determined the ISA Tile had been ... attached to the referenced stone block, thereby making it the original tile and not a copy:"

"Additional evidence was needed to associate the ISA Tile to the cavity and stone which would have been placed over the Western Gate of entranceway to the Citadel, otherwise the tile still might have been a copy of an even earlier mosaic. By examining his available photographic evidence, Dayvault noticed unique features on the large rock directly in front of the Citadel entranceway. The general characteristics were similar in configuration to the backside of the ISA Tile. Using skills from his former years of image analysis experience in the FBI Laboratory and Shroud research, he forensically determined the ISA Tile had been, in fact, at one time in its history, attached to the referenced stone block, thereby making it the original tile and not a copy[29].But significantly, Dayvault has left that item of crucial evidence out of his book (he briefly mentions it later on pages 282-283 with only a tiny, postage stamp sized, ~3 cm x ~3.5 cm = ~ 1.2 in. x ~1.4 in. photo), presumably because he had since realised that the underside of the mosaic does not match the stone block at this so-called "Western Gate Entrance"!

Dayvault claimed on page 228 that this "tunnel" is a "cylindrical semicircle" which is "the description for the location where the Shroud, Keramion, and lamp were hidden" and "That is exactly what the tunnel entrance depicts!" (his emphasis):

"The actual tunnel opening is not visible from the top of the mound while standing next to the Western Gate Monument. This is ... where most visitors stand while observing the great view of Sanliurfa. One has to walk all the way around the monument on a narrow trail to see the tunnel entrance with the missing block over the passageway. A `cylindrical semicircle' ... is the description for the location where the Shroud, Keramion, and lamp were hidden. That is exactly what the tunnel entrance depicts! " [228. Dayvault's emphasis]But it is not what the tunnel entrance depicts! The Official History states above that "the place where the image," tile and lamp "lay had the appearance of a semispherical cylinder" (my emphasis). The difference is that a "cylindrical semicircle" would be a cylinder which was flat at each end, and cut in half lengthwise; but a "semispherical cylinder" would be a cylinder with one end flat and the other end a half-sphere, and cut in half lengthwise. This does not fit Dayvault's tunnel so he changes the wording of the Official History! And apart from this windmill tower being "Byzantine and Islamic" and

therefore 11th- 12th century (see above), as shown by Dayvault's own photo on page 226 [Right (enlarge)] this tunnel is neither a "cylindrical semicircle" nor a "semispherical cylinder," but just brick tunnel (presumably for storage of grain to be milled and flour) with a pointed apex along its length. And as Dayvault's own photo below on page 223 of the opposite side of this tunnel entrance shows, it did not go all the way through. So (apart from

therefore 11th- 12th century (see above), as shown by Dayvault's own photo on page 226 [Right (enlarge)] this tunnel is neither a "cylindrical semicircle" nor a "semispherical cylinder," but just brick tunnel (presumably for storage of grain to be milled and flour) with a pointed apex along its length. And as Dayvault's own photo below on page 223 of the opposite side of this tunnel entrance shows, it did not go all the way through. So (apart from[Above (enlarge): Opposite side of what Dayvault calls the "Western Gate Monument" (which is actually a 11th-12th century windmill tower - see above), showing there is no way through what Dayvault claims was the "public gate of the city" (see above).]

everything else above, this tunnel could not have been what Dayvault claims on page 230 was the Official History's "Edessa city gate," that is "the public gate of the city" (see above).

This tile is historically known as the Keramion." [viii]. Wrong. As pointed out above the only tile the 945 Official History states had an image on it, was the one at Hierapolis, Syria. That tile was never at Edessa, but was transferred from Hierapolis, Syria to Constantinople in 968/969. The Official History says nothing about the tile at Edessa having an image on it. It was therefore this tile which had been at Hierapolis, Syria, that the Official History records had a "likeness of the divine [Jesus'] face" (see above) on it, and was transferred from Hierapolis, Syria, to Constantinople in 968/969, and later became known as The Keramion[30].

Further evidence against this Sanliurfa mosaic (see below) being the Keramion includes: 1) It is a mosaic, and even credulous first century

[Above (enlarge): "Mosaic face of Jesus, sixth century. Fragment from an unidentified location in Sanliurfa"[31]. Guscin and Wilson dated this Sanliurfa mosaic "somewhere between the sixth and seventh centuries"[32]. Dayvault in 2002[280] and Wilson and Guscin in 2008 were independently told by the Director of Sanliurfa Museum that the mosaic had been cut out of the wall of a Sanliurfa house[33]. This is a higher quality photo of the Sanliurfa mosaic, which Guscin found in a Sanliurfa magazine[34], and was first published outside of Turkey in Ian Wilson's 2010 book, "The Shroud" (see reference 31), thus preempting Dayvault who evidently sat on his 2002 discovery of the mosaic for ~9 years (2002-11) (see previous). Dayvault was aware that Wilson was the first to publish outside of Turkey an account of finding this mosaic, including the above photo of it, because on page 140 Dayvault refers to what presumably is private communication between him and Wilson about the mosaic:

"... Ian Wilson has indicated the place of its [the mosaic's] supposed original discovery was in Bireçik, a small town on the banks of the Euphrates River and in the western part of Sanliurfa Provence [sic]..." (see also below).But Dayvault does not give a reference to this communication with Wilson, and nowhere in Dayvault's book can I find (it does not have an index) where Dayvault credits Wilson or even cites his 2010 book.]

Hieropolitans would know that a mosaic was not an image but a lot of tiny tiles, none of which has an image, which together form the illusion of an image. So this Sanliurfa mosaic, Dayvault's "ISA tile," has no image, but only an illusion of an image which exists, not on the tile, but in the heads of humans looking at it. So this Sanliurfa mosaic cannot be the Keramion!

2) As pointed out in a previous post, the Greek word "keramion" is derived from keramos, which means "clay," "anything made of clay," and includes "a roofing tile"[35]. This fits with the Official History where the tile upon which the image of Jesus was transferred, which was later named "The Keramion," was one of "a heap of tiles which had been recently prepared," that is, clay roofing tiles. The exact same word keramion" occurs in Mark 14:13 and Luke 22:10 where it is translated "jar," as in a clay jar for carrying water[36]. But Dayvault described the base of the Sanliurfa mosaic, in which the mosaic tiles or tesserae were embedded, as "tufa" which is "a limestone commonly used for artwork" (my emphasis)[285]. So again, this Sanliurfa mosaic cannot be the Keramion!

3) Dayvault needs to plausibly explain how the Keramion, which disappeared during the 1204 sack of Constantinople[37] ended up in the wall of a house in Bireçik, a small town in Sanliurfa Province. He admitted in his PDF that "If his [the man who sold the mosaic to the museum] story were true, the ISA Tile would have been only a copy of an even earlier prototype" (Dayvault's emphasis)[38]. However in his book on page 280, Dayvault wrote that if this were true, it only "potentially could "preclude the possibility of its being the actual Keramion" (my emphasis). That is because Dayvault had since thought of two fantastic (as in fantasy) `explanations' of how what the man told the museum was true, yet the mosaic was the Keramion. Dayvault's first fantasy `explanation' was that because "Bireçik ... [is] about 20 miles [actually 35 miles = 56 kms] from Hierapolis, Syria, this Sanliurfa mosaic is the original Hierapolis tile and it was a copy of it which in 968 was taken to Constantinople and became known as the Keramion:

"Interestingly, Ian Wilson has indicated the place of its supposed original discovery was in Bireçik, a small town on the banks of the Euphrates River and in the western part of Sanliurfa Provence [sic], about 20 miles from Hierapolis, where the Keramion had been taken and later ordered retrieved and taken to Constantinople by Emperor Phokas in AD 966 or AD 968. Is that mere coincidence? Or, perhaps, could a copy have been sent to the emperor ... with the original remaining behind in Hierapolis (Edessa)? This would allow for the original to have been rediscovered and eventually passed on to the museum. The mosaic tile sent to Constantinople would most likely have been a copy in that the custodians would have wanted to retain the original" [140. Emphasis Dayvault's]But apart from Wilson and Guscin, world authorities on the Image of Edessa, having dated this mosaic to "between the sixth and seventh centuries" (see above), it not being made of clay (which is what keramion means - see above), and being a mosaic having no image on it (see above), Dayvault's "Hierapolis (Edessa)" reveals his confusion of the Hierapolis tile which had an image and the Edessa tile which didn't (see above). Then there are Dayvault's problems of explaining how the Emperor's experts were fooled when they would have been intimately familiar with the Hierapolis tile, and again how the tile ended up in the wall of a house in a small town in Sanliurfa Province, with no one knowing it was there, including the owner of the house.

Dayvault's second fantasy `explanation' is that the museum misunderstood what the seller (not "donor" because he sold it to the museum) told them. What the seller really said (according to Dayvault) was that the tile had been "hacked out ... of the wall ... [of] "the `house ...' of the king ... the Citadel"!:

"However, what if the donor had actually said, `It, the mosaic, had been 'hacked' out of a 'house' during 'renovations'? ... the donor could possibly be describing exactly what happened to the ISA Tile when it was removed centuries ago. Theoretically, describing the donor's statement and possible true meaning, the tile was `hacked out' of the wall cavity over the Western Gate tunnel, removed from its display, and hidden away, circa AD 57 in a tunnel cavity (in a small niche also `hacked out' to accommodate its shape) only to be rediscovered 468 years later during `house' renovations (flood repairs) in AD 525! The `house' he was possibly referring to was the `house' of the king, the winter palace on the Citadel. Now, his statement takes on a much different and relevant meaning!"[280-281]But where the tile had been since 525, how the seller obtained it, and how many thousands (if not millions) of US dollar equivalents he sold it for (since the seller knew it came from the Citadel) Dayvault doesn't say. Perhaps Dayvault imagines the following conversation between the seller and the Sanliurfa Museum Director:

Seller: "This mosaic tile was in AD 57 hacked out of a wall in the King's house, the Citadel, and I want one million US dollars for it."

Museum Director (hard of hearing): "You hacked it out of a wall in your house?"

Seller: "No, out of a wall in The Citadel. One of my ancestors hacked it off a stone block at the entrance of what is today the tunnel of the old windmill. The tile has been passed down through our family for 1447 years, from 525 to 1972. But I have inherited it and I want to sell it for one million dollars."

Museum Director (hearing only "I want to sell it"): "How much do you want for this mosaic tile you hacked out of a wall in your house?"

Seller (exasperated): "As I said, I want one million US dollars for it."

Museum Director (hearing only "one" and "dollar"): "It's a deal."

Dayvault's two contradictory fantasy `explanations' above just show the bankruptcy of his claim that this Sanliurfa mosaic is the Keramion. And what's more, it shows that Dayvault, at some level knows that his Keramion claim is false. As one who claims to be a Christian, Dayvault should publicly admit that his claim that this Sanliurfa mosaic is the Keramion is false, and offer to refund the money of the publisher and the purchasers of his book. I own over a hundred Shroud-related books and this book by Dayvault is easily the worst, and that includes my anti-authenticist books! If you are thinking about buying this book, I strongly recommend you don't, unless you like historical fiction/fantasy!

Notes

1. Dayvault, P.E., 2016, "The Keramion Lost and Found: A Journey to the Face of God," Morgan James Publishing: New York NY. [return]

2. Wilson, I., 2007, "Review of Brendan Whiting The Shroud Story, Harbour Publishing, Strathfield, New South Wales, Australia, 2006." 21 January. [return]

3. Wilson, I., 1974, "The Shroud in history," The Tablet, 13th April, p.12 (no longer online); Wilson, I., "The Shroud's History Before the 14th Century," in Stevenson, K.E., ed., 1977, "Proceedings of the 1977 United States Conference of Research on The Shroud of Turin," Holy Shroud Guild: Bronx NY, pp.44-45; Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition, pp.120, 307 n.16; Drews, R., 1984, "In Search of the Shroud of Turin: New Light on Its History and Origins," Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham MD, pp.36-37, 39-40; Wilson, I., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London, pp.112-113; Scavone, D.C., "The History of the Turin Shroud to the 14th C.," in Berard, A., ed., 1991, "History, Science, Theology and the Shroud," Symposium Proceedings, St. Louis Missouri, June 22-23, 1991, The Man in the Shroud Committee of Amarillo, Texas: Amarillo TX, pp.171-204, 171, 184; Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY, pp.104-105, 114-115; Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London, p.141; Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY, pp.152-153; Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN, pp.55, 57; Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY, pp.132-133; Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London, pp.110-111; Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, pp.2-3, 5-6; Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London, pp.140-141, 148, 299, 174; de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London, pp.186-187. [return]

4. Eusebius, c. 325, "The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius Pamphilus," Book I, Chapter XIII, Cruse, C.F., transl., 1955, Baker: Grand Rapids MI, Fourth printing, 1966, pp.46-47; Wilson, 1979, pp.127-128; Antonacci, 2000, p.133; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.107; Guerrera, 2001, pp.1-2. [return]

5. Ruffin, 1999, p.54; Guerrera, 2001, p.2. [return]

6. Drews, 1984, p.62; Scavone, D.C., 1989, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA, pp.80-81; Scavone, D.C., 2002, "Joseph of Arimathea, the Holy Grail and the Edessa Icon," Collegamento pro Sindone, October, pp.1-25, p.2. [return]

7. Markwardt, J.J., 1998, "Antioch and the Shroud," in Walsh, B.J., ed., 2000, "Proceedings of the 1999 Shroud of Turin International Research Conference, Richmond, Virginia," Magisterium Press: Glen Allen VA, pp.94-108, 94; Markwardt, J.J., 2009, "Ancient Edessa and the Shroud: History Concealed by the Discipline of the Secret," in Fanti, G., ed., "The Shroud of Turin: Perspectives on a Multifaceted Enigma," Proceedings of the 2008 Columbus Ohio International Conference, August 14-17, 2008, Progetto Libreria: Padua, Italy, p.384. [return]

8. Guerrera, 2001, p.2. [return]

9. Scavone, D.C., 2010, "Edessan sources for the legend of the Holy Grail," Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Scientific approach to the Acheiropoietos Images, ENEA Frascati, Italy, 4-6 May 2010, pp.1-6, 1. [return]

10. Wilson, 2010, p.119. [return]

11. Wilson, 1979, p.307; Wilson, 1998, pp.256, 268; Guscin, M., 2009, "The Image of Edessa," Brill: Leiden, Netherlands & Boston MA, pp.7-69; 154-157. [return]

12. "Court of Constantine Porphyrogenitus `Story of the Image of Edessa' (A.D. 945)," in Wilson, 1979, pp.272-290, 276-277. [return]

13. Wilson, 1979, p.132; Currer-Briggs, N., 1988, "The Shroud and the Grail: A Modern Quest for the True Grail," St. Martin's Press: New York NY, p.71; Currer-Briggs, N., 1995, "Shroud Mafia: The Creation of a Relic?," Book Guild: Sussex UK, p.74; Wilson, 1998, p.268; Whiting, B., 2006, "The Shroud Story," Harbour Publishing: Strathfield NSW, Australia, p.256. [return]

14. Wilson, 1979, pp.116, 151; Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY, pp.92; Morgan, R., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia, pp.36-37; Scavone, D.C., 1989, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA, p.85; Wilson, 1998, pp.148-149; Guerrera, 2001, pp.4-5; Scavone, D.C., "Underscoring the Highly Significant Historical Research of the Shroud," in Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition, p.xxvii; Wilson, 2010, p.165. [return]

15. Wilson, 1979, pp.280-281. [return]

16. Wilson, 1979, pp.131-132; Wilson, 2010, pp.131-134. [return]

17. Wilson, 1998, p.172. [return]

18. Scavone, 2002, p.10. [return]

19. Dayvault, P.E., 2011, "`FACE of the GOD-man': A Quest for Ancient Oil Lamps Leads to the Prototype of Sacred Art...and MORE!," Shroud University, May 11, p.24. [return]

20. Kidd, D.A., 1995, "Collins Paperback Latin Dictionary," HarperCollins: London, Latin-English p.37 & English-Latin p.29. [return]

21. Wilson, 1998, p.172; Scavone, 2010, p.1. [return]

22. "Edessa: Names," Wikipedia, 20 April 2016. [return]

23. "Sanliurfa," Google Maps: Earth, 29 April 2016. [return]

24. Piperno, R., 2011, "Sanliurfa: page one," A Rome Art Lover's Webpage. [return]

25. "A Guide to Southeastern Anatolia: Şanlıurfa Citadel, November 16, 2007. [return]

26. "Edessa: History," Wikipedia, 20 April 2016. [return]

27. "Siege of Edessa," Wikipedia, 16 February 2016. [return]

28. Dayvault, 2011, p.25. [return]

29. Ibid. [return]

30. Wilson, 1979, p.132; Currer-Briggs, N., 1984, "The Holy Grail and the Shroud of Christ: The Quest Renewed," ARA Publications: Maulden UK, p.19; Currer-Briggs, 1988, p.71; Whiting, B., 2006, "The Shroud Story," Harbour Publishing: Strathfield NSW, Australia, p.256 [return]

31. Wilson, 2010, plate 19a. [return]

32. Wilson, 2010, p.2. [return]

33. Ibid. [return]

34. Guscin, M., 2015, "MARK GUSCIN PhD THESIS 05.03.15," Royal Holloway, University of London, p.275. [return]

35. Thayer, J.H., 1901, "A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament," T & T. Clark: Edinburgh, Fourth edition, Reprinted, 1961, p.344. [return]

36. Zodhiates, S., 1992, "The Complete Word Study Dictionary: New Testament," AMG Publishers: Chattanooga TN, Third printing, 1994, p.858. [return]

37. Currer-Briggs, 1984, pp.23-24ff; Currer-Briggs, 1988, pp.72-73; Wilson, 1998, p.273; Currer-Briggs, 1995, pp.73-74; Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK, pp.107-108. [return]

38. Dayvault, 2011, p.7. [return]

Posted 25 April 2016. Updated 7 May 2025.