Copyright © Stephen E. Jones[1]

This is #47, "Prehistory of the Shroud (4)," of my series, "The evidence is overwhelming that the Turin Shroud is Jesus' burial sheet!" For more information about this "overwhelming" series, see the "Main index #1." As I wrote in "Prehistory" (1): "... this new series will help me write Chapter "9. Prehistory of the Shroud" of my book in progress, "Shroud of Turin: Burial Sheet of Jesus!" See 06Jul17, 03Jun18, 04Apr22, 13Jul22 & 8 Nov 22. While the in-line referencing makes a blog text harder to read, it saves time in renumbering out-of-order footnotes, and in my book each reference(s) between square brackets will be one numbered endnote. For more information about this "Prehistory" series, see "Prehistory (1)".

[Main index #1] [Previous: Prehistory of the Shroud (3) #46] [Next: Prehistory of the Shroud (5) #48]

711a Musa ibn Nusayr (640–716), the Muslim governor of North Africa, invaded Spain at Gibraltar[GM99, 127; BJ01, 31, 195; ADW] and in 718 captured the central Spanish city of Toledo[GM98, 15; BJ01, 32].

711b The Sudarium of Oviedo [see "616"] is taken from Toledo in its Arca Santa ("Holy Ark") chest to the northern Spanish kingdom of Asturias[BJ01, 29, 31, 195] where it was kept in a cave on a mountain called Monsacro, ten kilometres (6 miles) from what was to become the city of Oviedo[GM98, 15; BJ01, 32; GV01, 43].

722 A small Christian resistance force under the leadership of Pelagius of Asturias (c.685–737), aka. Pelayo, a Visigoth nobleman, defeated a much larger Muslim army at the Battle of Covadonga and then established the independent Christian kingdom of Asturias[GM99, 127; BJ01, 194]. This was the beginning of the Reconquista ("reconquest") of Spain after the muslim invasion of 711[BCW].

c. 725 Eighth century[WI79, 102; WM86, 105; SD91, 189, 191; WI91, 46H; WS00, 110], Christ Pantocrator fresco[WI79, 102; WI91, 46H; WS00, 110] (see below), heavily influenced by Byzantine icono-

[Above (enlarge): Bust of Christ Pantocrator from the catacomb of Pontianus, Rome[CPW]. Note in particular the Vignon marking on this 8th century fresco: "(2) three-sided [topless] `square' between brows"[SD91, 189, 191; WI91, 46H-47; WS00, 110; WI10, 142].

graphy[WI79, 102], in the depths of the catacomb of Pontianus, Rome[WM86, 105].

That the Image of Edessa/Shroud was the original of which this eighth century Byzantine icon was a copy, is evident in that it has at least eight[MR86, 77], and by my count eleven Vignon markings [see 18Mar12, 22Sep12, 27Apr14]:

"(1) Transverse streak across forehead, (2) three-sided [topless] `square' between brows, ... (5) raised right eyebrow, (6) accentuated left cheek, (7) accentuated right cheek, (8) enlarged left nostril, (9) accentuated line between nose and upper lip, ... (12) forked beard, (13) transverse line across throat, (14) heavily accentuated owlish eyes, (15) two strands of hair"[WI78, 82E].out of the fifteen found on the Shroud[WI79, 104-105; MR86, 77; IJ98, 152-153; WS00, 110; TF06, 250-251]!

In the 1930s French biologist Paul Vignon (1865-1943) was struck by this "small square set above the nose and open at the top" and other oddities which were unnatural and had no artistic merit[WJ63, 157; AM00, 124; TF06, 252; WI10, 142], found in Byzantine depictions of Jesus' face, which are also found in identical positions on the Shroud[WM86, 105, 107]:

"Vignon thought. If the Shroud was the progenitor of the traditional Christ, then something of the parent must have carried over into the offspring! Eventually, after a long and minute comparison of the face on the cloth with hundreds of paintings, frescoes and mosaics, he found the answer. Certain peculiarities were evident in the Shroud- peculiarities that were really accidental imperfections in the image or the fabric itself, and that served no artistic purpose. Yet, he observed jubilantly, these very oddities appeared again and again in a whole series of ancient art works, even though artistically they made no sense. Surely, this could mean only one thing: ancient artists had taken their conception of a bearded, long-haired man from the image on the Shroud, and had included the anomalies because of a feeling that they were in some mysterious way connected with the earthly appearance of Jesus. There were about twenty of these items in all [later refined by Wilson to fifteen[WI79, 104-105; MR80, 114-115; SH81, 15-16; TF06, 249-250]; some very pronounced, some just strongly characteristic of the face on the cloth. Most arresting were such things as a small square set above the nose and open at the top, the result either of a defect in the weave or a unique, accidental stain. There was the distorted appearance of the nose, swollen at the bridge with the right nostril enlarged; the abnormal shading of the right cheek; a curved transverse stain that ran senselessly across the forehead" (emphasis original)[WJ63, 157].So these "peculiarities" became known as the "Vignon markings"[CN88, 58; WI91, 46H; WS00, 111].

But as can be seen below, this "topless square" is merely the intersection of the man's horizontal eyebrows and a vertical flaw or change in the weave of the Shroud[SD91, 185; WI10, 142], which runs all the way down the

[Above (enlarge): Positive photograph of Shroud face[LM10a] showing outlined in red the `three sided' or `topless square' Vignon Marking no. 2, which can be seen is the intersection of the man's eyebrows and a vertical flaw or change in the weave; and superimposed on it the above 8th century bust of Christ in the catacomb of Pontianus, Rome, with the same "topless square" on it outlined in red.]

cloth (see 22Sep12), which explains its "starkly geometrical" shape[WI79, 103; WM86, 105; WI98, 159; WI10, 142]. Other Byzantine portraits of Christ which have the same `topless square' marking (albeit stylised) include the eleventh-century Daphni Pantocrator, the tenth-century Sant'Angelo in Formis fresco, the tenth-century Hagia Sophia narthex mosaic, and an eleventh-century portable mosaic in Berlin[WI79, 104]. And since this Pontianus catacomb was closed in 820 and only opened after 1852, a 14th century forger could not have known of the Vignon markings on this Pontianus fresco[WI98, 159; WI91, 168-169]. So as Wilson points out, just as "a single footprint on fresh sand provided for Robinson Crusoe the conclusive evidence that there was another human being ... on his island":

"Just as the viewing of a single footprint on fresh sand provided for Robinson Crusoe the conclusive evidence that there was another human being (later revealed as Man Friday) on his island, so the presence of this topless square on an indisputably seventh/eighth-century fresco virtually demands that the shroud must have been around, somewhere, in some form at this early date"[WI91, 168; WI10, 142].so is "this topless square on an ... eighth-century fresco" (and other Byzantine portraits of Christ) conclusive evidence that the Shroud existed in at least the eighth century! That is, six centuries before the earliest 1260 date given to it by radiocarbon dating[WI10, 142]. Moreover this `footprint in the sand' is not "single" - there are fourteen other different `footprints in the sand' which prove beyond reasonable doubt that the Shroud existed in at least the eighth century[WS00, 110]!

723 From 723 to 842 was a period of iconoclasm[WI79, 254; WI98, 267; WI10, 300] (Gk. eikon = "image" + klastes = "breaker"[ICD]). In 723 the Muslim Caliph Yazid II (r. 720–24) issued an edict in Damascus ordering the destruction of all Christian icons in his Umayyad Caliphate[YTW]. An outbreak of image-smashing ensued[WI79, 254]. For the next 120 years both the Byzantine and the Moslem empires suffer outbreaks of iconoclasm in which countless icons and artistically created images of Jesus are destroyed"[WI98, 26; AM00, 129; WI10, 300].

726 Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (r. 717–41), under pressure from Islam[OM10, 28-29] decreed that all icons in the Byzantine Empire were to be destroyed as idolatrous[SD91, 184; GV01, 4]. As a result countless thousands of images of Christ were destroyed[WI79, 254; SD91, 184], which explains the paucity of visual documentation of the Image of Edessa/Shroud before the tenth century[SD91, 184]. But the Image of Edessa/Shroud survived because its imprint was obviously not artistically created[WI79, 254; SH81, 19; WI98, 267; OM10, 26]. Also the Cloth was kept hidden in faraway Muslim-controlled Edessa[OM10, 26], where paradoxically it was safer than it would have been in Christian Constantinople[OM10, 30]!

Indeed the Edessa Image was the main argument used against the iconoclasts[AM00, 129] [see "730" below]. However, most copies of the Image of Edessa/Shroud were destroyed[WI79, 36; WI91, 102,135; PM96, 193].

730 St. John of Damascus (c.675–749), aka John Damascene, in his De

[Right (enlarge): A "himation was with the ancient Greeks ... a loose robe ... worn over [clothes] ... alike for both sexes"[HMW].]

Imaginibus (On Images), writing in defence of images at the outset of the Iconoclastic Controversy[OM10, 26, 30], mentioned "sindons" ("shrouds") among the relics of the Passion to be venerated on account of their connection with Jesus[BP28, 146; BA34, 52; AF82, 17; CN84, 16]. That John was referring to the Image of Edessa/Shroud is evident in that he cited the Abgar V legend [see "SD97"] in support of its significance as an image[OM10, 26]. John also referred to the Edessa image as a "himation"[DR84, 39; IJ98, 110; WI98, 152; AM00, 132; GM09, 151-152; OM10, 27; WI10, 152; DT12, 186], a Greek outer garment [imation Mt 5:40; 9:20-21; 14:36; Mk 5:27-30; Jn 19:2; Ac 12:8][ZS92,773-774] about two yards (1.83 m) wide by three yards (2.74 m) long[DR84, 39; WI98, 152, 267; OM10, 26-27], which means that the full size of the Cloth was then known[OM10, 27, 36]. Finally John referred to the Edessa Image as "the miraculously imprinted image" that it "has been preserved up to the present time"[DR84, 62; GM09, 151-152; OM10, 27]. Again, this can only be the Shroud, more than five centuries before its earliest 1260 radiocarbon date, and more than six centuries before its first appearance in undisputed history at Lirey, France, in c. 1355!c. 750 The Venerable Bede (c.673–735) had been told that in the Liber Pontificalis (Book of the Popes), Pope Eleutherus (r. 174-189)[SD02; SD10, 3] had received a letter from Lucio Britannio rege, probably between 183 and 189[SD97, 35], asking for Christian missionaries to be sent that he might become a Christian[WI98, 171; SD02] and to help convert those within his lands to Christianity[SD02; SD10, 3]. But this was a c. 530 interpolation by a copyist that: "This pope received a letter from British King Lucius [Latin Britannio rege Lucio] asking that he might be made a Christian through his agency"[WI98, 171, 266; SD02; SD97, 32]. Bede therefore thought there must have been a previously unknown second century British King Lucius[SD02; SD10, 3], so he wrote in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People that Lucius was a British king and that Christianity had commenced in Britain in the second century[WI98, 171, 267; SD10, 3]. But as the German church historian Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930) wrote in 1904, the only King Lucius who converted to Christianity in the second century was Lucius Abgar VIII of Edessa[WI98, 171-72, 267; SD10, 3] [see "183"], full name Lucius Aelius Septimius Megas Abgarus VIII[SD97, 35; WI98, 264], who took the forenames Lucius Aelius to honour his Roman overlord, the Emperor Lucius Aelius Commodus (r. 180-192)[WI98, 167], and who lived in the time of Pope Eleutherus[SD10, 3]. [see "202"]. And "Britannio" was short for "Britium Edessenorum," which in turn was the Latin rendering of the Syriac "Birtha of the Edessenes" which was the name of Agbar VIII's Edessa Citadel[SD02; SD10, 4] [see "205"]. But since every subsequent British historian and clergyman read Bede's Ecclesiastical History[SD02; SD10, 4], his non-existent King Lucius of Britain became an important `reality' as the king who brought Christianity to Britain in the second century[WI98, 172; SD10, 4]! It was due to Bede's misunderstanding[WI98, 172] that the French creators of the Holy Grail legends located their stories not in France but in England[SD10, 4]. From which the legend arose that Joseph of Arimathea had visited Englandl[SD02; SD10, 4] and in Glastonbury, from his staff a tree miraculously grew[GTW] (it's claimed descendent my wife and I saw at Glastonbury when we visited her aunt there in 1997)!

754 A copy of the Image of Edessa/Shroud called the  Acheropita, a

Acheropita, a

[Left (enlarge)[WI91, 46C]: The Acheropita 'holy face' that for at least twelve hundred years has been preserved in Rome's Sancta Sanctorum chapel, originally the popes' private chapel before papal residence shifted to the Vatican, under Pope Nicholas V (r. 1447-55). The icon's cover is thirteenth-century, and its 'face' a crude over-painting, but beneath lies a near totally-effaced original that dates at least as far back as AD 754[WI91, 46C]. Note that the head is centred in landscape aspect, exactly as it is on the Image of Edessa/Shroud[WI79, 120; WI91, 141; WI98, 152; WS00, 140].]

Latinization of acheiropoietos[WI91, 143] ("not made with hands" - Mk 14:58; 2Cor 5:1; Col 2:11) was in the Sancta Sanctorum Chapel of the Vatican's Lateran Palace by at least 754[WI91, 162]. That is because when Rome was threatened by the Germanic Arian Lombards after their capture of Ravenna in 751, Pope Stephen II (r. 752-57) in 754 personally carried this Acheropita barefoot at the head of a huge procession in Rome, praying for this icon to be instrumental in the deliverance of their city[WI91, 144]. Yet it is probably much earlier than that, being reliably regarded as having been brought to Rome in the last years of the sixth century by Pope Gregory I the Great (r. 590-604)[WI91, 143]. Before he became Pope, Gregory had been the papal legate in Constantinople at the court of the Byzantine Emperor Tiberius II (r. 574-82), when interest in acheiropoietic images, after the discovery of the Image of Edessa in 544 (see "544")[WI91, 140], was at its peak in Constantinople[WI91, 143]. Tiberius II's throne had a majestic image of Christ, since destroyed, derived from the Image of Edessa, which had been set there by his predecessor, Justin II (r. 565-574)[WI91, 143]. It is therefore very likely that this Acheropita icon now in the Sancta Sanctorum Chapel in Gregory's Lateran Palace in Rome, was specially commissioned by Gregory before 590 for him to take back to Rome[WI91, 144]! If so, that is at least ~670 years before the earliest earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud and at least ~765 years before the Shroud's first appearance in undisputed history at Lirey, France, in c. 1355!761 The Arca Santa (Holy Chest) containing the Sudarium of Oviedo

(see above) and other relics, is placed in the primitive Monastery of San Vicente, near where the city of Oviedo was later founded[BJ01, 195].

769 In his Good Friday sermon delivered in Rome at the Lateran Council of 769[IJ98, 110; SD02; OM10, 27], Pope Stephen III (r. 768–72), opposing the Iconoclast movement (see above)[SD89b, 318], spoke in favor of the use of sacred images[GV01, 4; SD02]. In that sermon, Stephen referred to the Abgar V legend [see "50"] mentioning the Edessa towel (the Image of Edessa/Shroud) with its miraculous facial image[SD89, 88; SD02]. Stephen quoted Jesus' supposed response to Abgar's request for a cure:

"Since you wish to look upon my physical face, I am sending you a likeness of my face on a cloth ..."[SD89, 318]And as we shall see in a twelfth century updated version of Stephen's 769 sermon [see "pre-1130"[WI98, 270]], a copyist had interpolated a reference to Jesus' "whole body" being visible on the Edessa cloth, reflecting the later discovery in Constantinople that Jesus' body was imprinted on the Image of Edessa/Shroud, not just His face[SD89, 88; WR10, 105].

787 The iconoclasm of Leo III (see above) was continued by his son Constantine V Coproymos (741–75)[CD82, 27; CFW], and grandson Leo IV the Khazar (r. 775–80)[OM10, 30]. It was only after the death of Leo IV that the first period of iconoclasm was brought to an end in 787 by the Second Council of Nicaea[SCW], the last of the first seven ecumenical councils of the whole Christian church, both East and West[OM10, 30]. The Council debated the veneration of holy images[FM15, 54] and in particular about the Image of Edessa not having been produced by the hand of man[FM15, 54]. Leo, the Lector (Reader) of Constantinople's Hagia Sophia Cathedral, reported to the Council that he had visited Edessa and seen there "the holy image made without hands and adored by the faithful"[WI98, 267; OM10, 27, 30; WI10, 154]. The Council endorsed the veneration of images[GV01, 4], and in particular the Image of Edessa, the "one `not made by human hands' [acheiropoieton] that was sent to Abgar"[IJ98, 111; GV01, 4; OM10, 30]. It was the main argument used by the bishops to defend the legitimacy of the use of sacred images[GV01, 4] and to which the iconoclast bishops had no reply[GM69].

812 King Alfonso II of Asturias (r. 783, 791-842), built a chapel in his capital Oviedo, which was later incorporated into Oviedo Cathedral. In

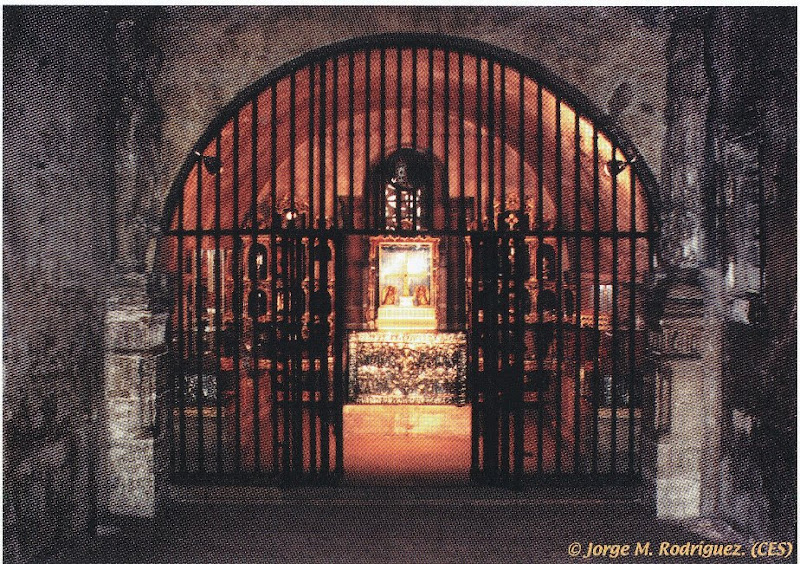

[Left (enlarge)[HD11]: The 9th century chapel built by King Alfonso II, within which was the Holy Chamber (Cámara Santa) that held the Holy Chest (Arca Santa), which contained the "face cloth [Gk soudarion], which had been on Jesus' head" (Jn 20:7) [see "30"], later known as the "Sudarium of Oviedo," and other relics (see below). See also 25May16].]

that chapel was a Cámara Santa (Holy Chamber), to hold the Arca

[Right (enlarge[BJ01, pl. 3]): "The Camara Santa, or Holy Chamber, within the chapel built in 812 by King Alfonso II, to hold the Holy Chest (see below) which contained the Sudarium of Oviedo and other relics. The chest can be seen past the metal bars in the centre background.]

Santa (Holy Chest - see 761 above) which contained the Sudarium of Oviedo and other relics, that had been in the nearby Monastery of San Vicente since 761 (see 761)[BJ01, 195].

814 A second iconoclast period (814-42) (see 723 above for the first) began early in the reign of Byzantine Emperor Leo V the Armenian (r. 813-20)[LK53, 296]. However:"Leo V ... was much milder in his enforcement of the ban than had been some of his predecessors and the attack was not so much on icons in general as upon some of the uses of them, especially in worship in private houses. The veneration of icons seems to have continued outside the capital, especially in Greece, the islands, and much of Asia Minor."[LK53, 296]The Patriarch of Constantinople (equivalent to Archbishop), Nicephorus I (r. 806-15) was an early opponent of Leo V's iconoclasm but he was removed from office by excommunication in 815[NIW]. A former painter of icons, the very learned John VII (nicknamed "Grammatikos"), had by 814 become an iconoclast and was later appointed Patriarch John VII of Constantinople (r. 837-43) by Emperor Theophilos (r. 829-42)[JVW]. That the Image of Edessa/Shroud was, as in the first Iconoclastic Period (see 723 above), cited as a major argument against the banning of images, is evident from Wikipedia's summary of iconophile arguments:

"Much was made of acheiropoieta, icons believed to be of divine origin ... Christ [was] ... believed in strong traditions to have sat ... for [his] ... portrait .. to be painted[BIW]!For the end of the second iconoclastic period see future ["842] below.

c. 820 The Stuttgart Psalter is a richly illuminated 9th-century psalter, considered one of the most significant of the Carolingian period (780-900 — during the reign of Charlemagne (r. 768-814) and his immediate heirs)[SPW]. Written in Carolingian minuscule, it contains 316 images illustrating the Book of Psalms according to the Gallican Rite[SPW]. It has been archived since the late 18th century at the Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart[SPW]. In Folio 43v

[Above (enlarge)[JBS]: Extract from folio 43v (keep clicking "+" to continuously enlarge the page) of the 9th century (c. 820) Stuttgart Psalter, presumably painted by a Byzantine artist during the Carolingian period (780-900), in the Aachen, Germany capital of Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne (r. 800–14). See 21Oct13 that this was posted on Dan Porter's blog by a Max Patrick Hamon.]

of the Psalter Jesus is depicted being scourged (presumably interpreting Psalm 39:10 as a Messianic prophecy). This 9th century depiction of Jesus being scourged has many Shroud-like features:

• Jesus is fully naked from the back (unique in medieval art);

• Jesus is being scourged by two scourgers, which was a modern discovery on the Shroud[BP53, 92; RG77, 61; SH81, 36; ZF88, 18] and required a close inspection of the full-length Shroud, front and back;

• The two flagrums each have three thongs with a ball at the end of each. This also was a modern discovery[BA34, 34-35; SH81, 118;

[Above (enlarge): Close-up of the left scourger's, three-thonged, metal ball tipped, Roman flagrum in folio 43v of the 9th century (c. 820) Stuttgart Psalter. Compare its historical accuracy with the flagrum below.]

WI98, 42; AM00, 100] which also required a close inspection of the entire Shroud;

[Left (enlarge): A reconstruction of a Roman flagrum by Paul Vignon[WS00, 56]. One similar to this was recovered from the Roman city of Herculaneum which, with its neighbour Pompeii[WI79, 48], was buried in the eruption of Mt Vesuvius in AD 79[DT12, 122; HLW].]

• The scourge marks are bleeding realistically;

• Jesus' feet are at an angle (as the man on the Shroud's appear to be).

• The unnaturally long and strangely configured fingers on the free hand of the scourger on the right, is in the shape of the epsilon (or reversed 3) bloodstain on the Shroud man's forehead (see below),

[Above (enlarge): The fingers of the scourger on the left of Jesus on the Stuttgart Psalter (left) [see above]; the reversed 3 bloodstain on the Shroud horizontally flipped (centre); and the fingers of the scourger on the right of Jesus on the Stuttgart Psalter (right). As can be seen there is a close match between the shape of reversed 3 bloodstain on the Shroud and the fingers of the scourger on the right (right).]

and if that bloodstain photo is flipped horizontally (because the scourgers' fingers are at the back of Jesus but the reversed 3 bloodstain is at the man on the Shroud's front), it then has the same basic shape as the scourger's fingers! And there is no reason why the scourger on the left would be pointing to his head and the scourger on the right would be pointing to Jesus' head.

The unknown 9th century artist must therefore have seen either the full-length Shroud, which was then in Edessa [see "544"], or an accurate copy of it. Either way, this would refute that part of Ian Wilson's theory that only after the Image of Edessa/Mandylion was taken from Edessa to Constantinople in 944 (see "944b"), was it discovered that behind its face of Jesus was the full-length Shroud:

"All this makes all the more intriguing the evidence that someone, sometime after the Mandylion's arrival in Constantinople [in 944], seems to have undone the gold trelliswork covering the cloth, untwined the fringe from the surrounding nails, carefully unfolded the cloth, and, for the first time since the days of the apostles, set eyes on the concealed full-length figure"[WI79, 157-158].842 The second iconoclast period ended with the death of Emperor Theophilos in 842 (see above) and his two year-old son Michael III (r. 842-67) succeeding him[MTW]. During Michael III's minority the Empire was governed by his mother, the Empress Theodora (r. 842-55) [TWW], as his regent[MTW]. Theodora was an iconodule[TIW] and in 843 she reintroduced the minting of coins bearing the face of Christ, with Shroud-like features[PM96, 194; FM15, 116-117]. Also, through

[Above (enlarge)[Vignon markings" features [see 18Dec17], and on the reverse (right) Michael III and Theodora, indicating her regency during her son's minority.]

her influential minister Theoktistos (r. 842-55)[TKW], Theodora deposed the iconoclast Patriarch John VII of Constantinople (see above) and replaced him with the iconodule Patriarch Methodius I of Constantinople (r. 843-47)[MTW]. That brought to an end the the second period of Byzantine iconoclasm[MCW].

Notes:

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to extract or quote from any part of it (but not the whole post), provided the extract or quote includes a reference citing my name, its title, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

Bibliography

ADW. "AD 711," Wikipedia, 8 September 2023.

AF82. Adams, F.O., 1982, "Sindon: A Layman's Guide to the Shroud of Turin," Synergy Books: Tempe AZ.

AM00. Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY.

ASW. "Arca Santa," Wikipedia, 14 January 2022.

BA34. Barnes, A.S., 1934, "The Holy Shroud of Turin," Burns Oates & Washbourne: London.

BA91. Berard, A., ed., 1991, "History, Science, Theology and the Shroud," Symposium Proceedings, St. Louis Missouri, June 22-23, 1991, The Man in the Shroud Committee of Amarillo, Texas: Amarillo TX.

BCW. "Battle of Covadonga," Wikipedia, 28 March 2024.

BIW. "Byzantine Iconoclasm: Iconophile arguments," Wikipedia, 30 December 2023.

BJ01. Bennett, J., 2001, "Sacred Blood, Sacred Image: The Sudarium of Oviedo: New Evidence for the Authenticity of the Shroud of Turin," Ignatius Press: San Francisco CA.

BP28. Beecher, P.A., 1928, "The Holy Shroud: Reply to the Rev. Herbert Thurston, S.J.," M.H. Gill & Son: Dublin.

BW57. Bulst, W., 1957, "The Shroud of Turin," McKenna, S. & Galvin, J.J., transl., Bruce Publishing Co: Milwaukee WI.

BP53. Barbet, P., 1953, "A Doctor at Calvary," [1950], Earl of Wicklow, transl., Image Books: Garden City NY, Reprinted, 1963.

CN84. Currer-Briggs, N., 1984, "The Holy Grail and the Shroud of Christ: The Quest Renewed," ARA Publications: Maulden UK.

CN88. Currer-Briggs, N., 1988, "The Shroud and the Grail: A Modern Quest for the True Grail," St. Martin's Press: New York NY.

CD82. Crispino, D.C., 1982, "The `Crucifixion' of Santa Maria Antiqua," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 5, December, 22-29.

CFW. "Constantine V: Constantine's support of iconoclasm," Wikipedia, 17 March 2024.

CPW. "Catacomba di Ponziano," Google Translate, Wikipedia, 16 July 2022.

DR84. Drews, R., 1984, "In Search of the Shroud of Turin: New Light on Its History and Origins," Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham MD.

DT12. de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London.

EP17. "Four and a half months to restore the Holy Ark of the Cathedral of Oviedo," Europa Press, 3 May 2017.

FM15. Fanti, G. & Malfi, P., 2015, "The Shroud of Turin: First Century after Christ!," Pan Stanford: Singapore.

GM69. Green, M., 1969, "Enshrouded in Silence: In search of the First Millennium of the Holy Shroud," Ampleforth Journal, Vol. 74, No. 3, Autumn, 319-345.

GM98. Guscin, M., 1998, "The Oviedo Cloth," Lutterworth Press: Cambridge UK.

GM99. Guscin, M., 1999, "Recent Historical Investigations on the Sudarium of Oviedo," in WB00, 127.

GM09. Guscin, M., 2009, "The Image of Edessa," Brill: Leiden, Netherlands & Boston MA.

GTW. "Glastonbury Thorn," Wikipedia, 27 March 2024.

GV01. Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL.

HD11. Ho Diéguez, C.V., 2011, "Patrimonio Ibérico – Monumentos de Oviedo y el Reino de Asturias," ("Iberian heritage - Monuments of Oviedo and the Kingdom of Asturias" - Google Translate), 26 May (no longer online).

HLW. "Herculaneum," Wikipedia, 6 April 2024.

HMW. "Himation," Wikipedia (Danish), 7 November 2022.

ICD. "iconoclast," Vocabulary.com, 2024.

IJ98. Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY.

JBS. "Jesus being scourged," Württembergischen Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (Wurttemberg State Library, Stuttgart), Stuttgart Psalter - Cod.bibl.fol.23, 43v.

JVW. "John VII of Constantinople," Wikipedia, 6 November 2023.

LK53. Latourette, K.S., 1953, "A History of Christianity: Volume 1: to A.D. 1500," Harper & Row: New York NY, Reprinted, 1975.

LM10a. Extract from Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002 Face Only Vertical," Sindonology.org.

LM10b. Extract from Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002 Face Only Vertical," Sindonology.org.

MCW. "Methodios I of Constantinople," Wikipedia, 25 November 2023.

MR80. Morgan, R.H., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia.

MR86. Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY.

MTW. "Michael III," Wikipedia, 1 April 2024.

NIW. "Nikephoros I of Constantinople," Wikipedia, 25 February 2024.

OM10. Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK.

PM96. Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1996, "The Enigma of the Shroud: A Challenge to Science," Scerri, L.J., transl., Publishers Enterprises Group: Malta.

RG77. Ricci, G., "Historical, Medical and Physical Study of the Holy Shroud," in SK77, 58-73.

SCW. "Second Council of Nicaea," Wikipedia, 14 March 2024.

SD89a. Scavone, D.C., 1989, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA.

SD89b. Scavone, D., "The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople: The Documentary Evidence," in SR89, 311-329.

SD91. Scavone, D.C., 1991, "The History of the Turin Shroud to the 14th C.," in BA91, 171-204.

SD97. Scavone, D., 1997, "British King Lucius and the Shroud," Shroud News No. 100, February, 30-39.

SD02. Scavone, D.C., 2002, "Joseph of Arimathea, The Holy Grail & the Edessa Icon," BSTS Newsletter, No. 56, December.

SD10. Scavone, D.C., 2010, "Edessan sources for the legend of the Holy Grail," Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Scientific approach to the Acheiropoietos Images, ENEA Frascati, Italy, 4-6 May 2010, 1-6.

SH81. Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1981, "Verdict on the Shroud: Evidence for the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ," Servant Books: Ann Arbor MI.

SK77. Stevenson, K.E., ed., 1977, "Proceedings of the 1977 United States Conference of Research on The Shroud of Turin," Holy Shroud Guild: Bronx NY.

SPW. "Stuttgart Psalter," Wikipedia, 29 January 2021.

SR89. Sutton, R.F., Jr., 1989, "Daidalikon: Studies in Memory of Raymond V Schoder," Bolchazy Carducci Publishers: Wauconda IL

TF06. Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," [1983], Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition.

TIW. "Theodora (wife of Theophilos): Empress consort," Wikipedia, 15 December 2023.

TKW. "Theoktistos," Wikipedia, 3 March 2024.

TWW. "Theodora (wife of Theophilos)," Wikipedia, 15 December 2023.

WB00. Walsh, B.J., ed., 2000, "Proceedings of the 1999 Shroud of Turin International Research Conference, Richmond, Virginia," Magisterium Press: Glen Allen VA, 122-141.

WI78. Wilson, I., 1978, "The Turin Shroud," Book Club Associates: London.

WI79, Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus Christ?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised.

WI91. Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London.

WI98. Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY.

WI10. Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London.

WJ63. Walsh, J.E., 1963, "The Shroud," Random House: New York NY.

WM86. Wilson, I. & Miller, V., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London.

WR10. Wilcox, R.K., 2010, "The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery," [1977], Regnery: Washington DC.

WS00. Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London.

Michael III - Byzantine Coinage," SB 1687, WildWinds.com, October 25, 2016.

YTW. "Yazid II," Wikipedia, 16 December 2023.

ZS92. Zodhiates, S., 1992, "The Complete Word Study Dictionary: New Testament," AMG Publishers: Chattanooga TN, Third printing, 1994.

ZF88. Zugibe, F.T., 1988, "The Cross and the Shroud: A Medical Enquiry into the Crucifixion," [1982], Paragon House: New York NY, Revised edition.

Posted 26 March 2024. Updated 20 August 2025.