This is part #8, "Shroud's 1260-1390 radiocarbon date is against the preponderance of the evidence (1)," in my "Steps in the development of my radiocarbon dating of the Turin Shroud hacker theory" series. For more information about this series see part #1, "Hacking an explanation & Index." References "[A]", etc., will be to that part of my original post. Emphases are mine unless otherwise indicated.

[Index: #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #7, #9, #10, #11, #12]

[Previous: "Dr Jull's and Prof. Ramsey's prompt, misleading and false replies" #7] [Next: "VT-100 terminal to a DEC mini-computer, Timothy Linick and Karl Koch" #9]Continuing with tracing the steps in the development of my radiocarbon dating of the Shroud hacker theory in my early 2014 posts: "Were the radiocarbon dating laboratories duped by a computer hacker? (1)," "(2)," "(3)," "Summary," "My replies to Dr. Timothy Jull and Prof. Christopher Ramsey," and now "Were the radiocarbon dating laboratories duped by a computer hacker?: Revised #1".

The Shroud was radiocarbon dated to 1260-1390 = 1325 ±65 On 13 October 1988 it was announced by the British Museum's Dr M. Tite, Oxford's Prof. E. Hall and Dr R. Hedges at a press conference in the British Museum, London, and simultaneously in Turin by Archbishop Ballestrero, that three radiocarbon dating laboratories, Arizona, Zurich and Oxford, had radiocarbon-dated the Shroud of Turin as 1260-1390!"(See part #6)[2]. Then on 16 February 1989 the science journal Nature reported that:

"... samples from the Shroud of Turin have been dated by accelerator mass spectrometry in laboratories at Arizona, Oxford and Zurich ... The results provide conclusive evidence that the linen of the Shroud of Turin is mediaeval ... AD 1260-1390"[3].The midpoint of 1206-1390 is 1325 ±65 years[4], which is

only ~30

only ~30[Above (enlarge): Pilgrim's badge[5] from the first undisputed exposition of the Shroud at Lirey, France in c.1355[6].]

years before the Shroud was first exhibited in undisputed history at Lirey, France in c. 1355[7].[A]

Against the preponderance of the evidence (1) This was against the preponderance of the evidence[8], including historical evidence (see following in reverse chronological order) that the Shroud existed many centuries before 1260, the earliest possible radiocarbon date[9].

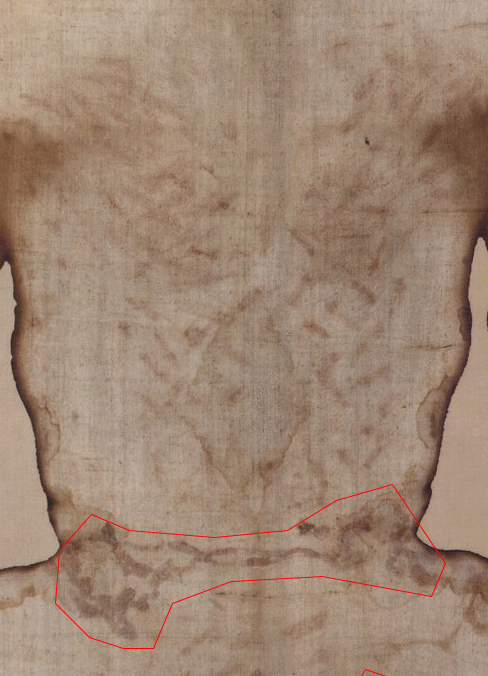

c. 1225 Around 1225 the frescoes in the 12th century[10] chapel of the Holy Sepulchre in Winchester Cathedral, England, were repainted[11]. In the deposition scene of Jesus having been taken down from the

[Above (enlarge): Deposition fresco in Holy Sepulchre Chapel, Winchester Cathedral[12]. Note the double body length shroud about to be placed over Jesus, in a fresco painted in at least 1225, 35 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud!]

cross by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, the unknown artist painted behind St John and Nicodemus a fourth man carrying a double-length shroud, intended to go over Jesus's head, body and down to his feet, exactly as the Shroud does[13].[B]

c. 1212 Gervase of Tilbury (c.1150–c.1228), a widely travelled thirteenth century, English born but Rome-educated[14], canon lawyer, statesman and writer[15], referring in his Otia Imperialia which was written between 1210 and 1214[16], to the story of the cloth upon which Jesus had impressed an image of His face and sent it to King Abgar V of Edessa, added that:

"... it is handed down from archives of ancient authority that the Lord prostrated himself full length on most white linen, and so by divine power the most beautiful likeness not only of the face, but also of the whole body of the Lord was impressed upon the cloth"[17].This is one of a number (see Ordericus Vitalis below) of altered versions of the Abgar story which substituted for the miracle of Jesus' pressing his face onto a cloth to explain Jesus' face on the Image of Edessa, a scenario by which Jesus laid his whole body upon a cloth in order to produce a likeness of his whole body[18]. It is so self-evidently preposterous that Jesus would have in life (let alone publicly!) laid His naked body on a cloth to imprint His image on it[19], that this can only be an early 13th century reference to the Shroud, nearly a half-century before the earliest radiocarbon date of 1260, and mentioned in archives which were "ancient"[20] even then![C]

1203: French crusader knight Robert de Clari, a chronicler of the Fourth Crusade (1202–4)[21], wrote in his 1204 diary The Conquest of Constantinople[22] what he saw in Constantinople in late 1203:

"... there was another church which was called My Lady Saint Mary of Blachernae, where was kept the sheet [sydoines] in which Our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday rose up straight, so that one could clearly see the figure [figure] of Our Lord on it; and no one, neither Greek nor French, knew what became of this sheet after the city was taken"[23].The word sydoines is Old French for the Greek word sindon, a linen sheet, used in the Gospels for Jesus' burial shroud (Mt 27:59; Mk 15:46; Lk 23:53), and the word figure is Old French for "bodily form"[24]. So in 1203 there existed in Constantinople a linen shroud with an imprint of Christ's body on it, over a half-century before the earliest radiocarbon date, 1260[25]. But then it would be the "sindon which God wore," mentioned in a letter of of 958 by Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (r. 913-959) as already in the imperial relic collection[see "958"], over 300 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud[26]![D]

1201-1204: The Holy Face of Laon (French: "Sainte Face de Laon"[27]) is a glazed panel painted presumably at Constantinople between 1201 and 1204[28], or even in the second half of the 12th

[Above (enlarge): "Icon of the Holy Face (Mandylion) of Laon. Purchased in 1249 in Bari (Italy) by Jacques Pantaleon, later to become Pope Urban"[29].]

century (e.g. c.1167-1198[30]). In 1249, Jacques Pantaleon (1195–1264), then Archdeacon of Laon[31], and later to become Pope Urban IV (r.1261–1264)[32], gave the icon to his sister Sibylle, the abbess of a nearby convent at Montreuil-en-Thierache[33]. It is now kept in the Cathedral of Laon, Picardy, France[34]. The icon is actually a copy of the Image of Edessa or Mandylion[35], as its background has a trellis pattern[36] like other depictions of the Image. It also shows a brown monochrome, rigidly front facing, disembodied head of Jesus on cloth, strongly reminiscent of the Shroud[37]. This icon corresponds more closely to the face on the Shroud than any other[38], having 13 of the 15 Vignon markings (see part #2)[39]. It also bears an inscription in ancient slavonic: OBRAZ GOSPODIN NA UBRUSJE "the portrait of the Lord on the cloth"[40], which must mean that the artist worked directly from the Shroud[41], which was in Constantinople between 944 and 1204[42]. But since the Sainte Face dates from the beginning of the thirteenth century (or even from the end of the 12th century), and it is a copy of the Shroud image, then the Shroud must date from well before 1200[43]. This cannot be reconciled with the 1260-1390 radiocarbon dating[44].[E]

1201: Nicholas Mesarites, the Keeper[45] of Constantinople's Pharos Chapel relic collection, in 1201 wrote:

"In this chapel Christ rises again, and the sindon with the burial linens is the clear proof ... The burial sindon of Christ: this is of linen, of cheap and easily obtainable material, still smelling fragrant of myrrh, defying decay, because it wrapped the mysterious [aperilepton], naked dead body after the Passion"[46].The Greek word aperilepton means "un-outlined"[47], "uncircumscribed"[48] or "indefinable"[49] (Greek a = "not" + peri = "around" + "lepton" = "thin"[50]), and is a unique descriptor of the image on the Shroud which has no outline[51]. Moreover, Mesarites stated that Christ's body was naked but except for the Pray Codex (see below) not until the fourteenth century, and then only rarely, was Christ's body depicted as naked[52]. These two unique descriptors of the Shroud, "un-outlined" and "naked," which were also descriptors of Jesus' image on a "sindon" (shroud) in Constantinople's relic collection in 1201, are further evidence that the Shroud was already in Constantinople at the very beginning of the thirteenth century[53], nearly 60 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud![F]

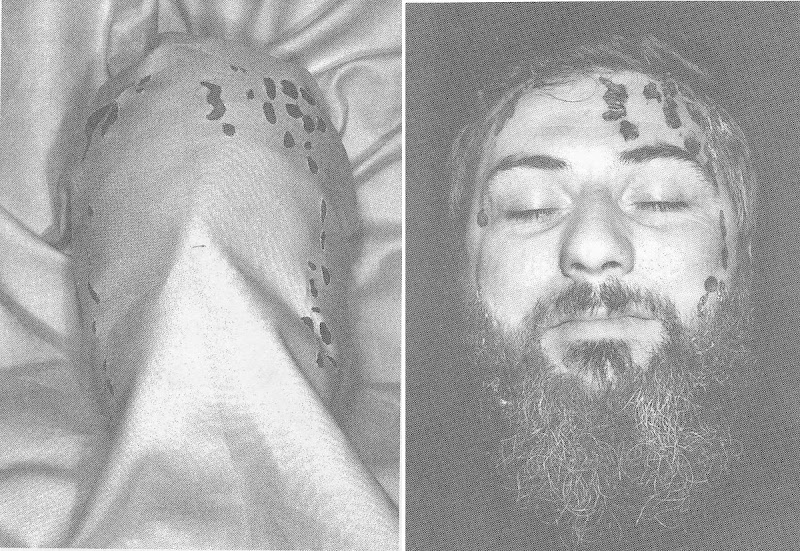

1192-95 The Hungarian Pray Manuscript, or Codex, is dated 1192-95[54], having been made at the Benedictine monastery of Boldva in Hungary between those years[55]. Hungary was then ruled by King

[Above (enlarge): "The Pray Codex, 1192-95:

"The Codex Pray, Pray Codex or The Hungarian Pray Manuscript is a collection of medieval manuscripts. In 1813 it was named after György Pray, who discovered it in 1770. It is the first known example of continuous prose text in Hungarian. The Codex is kept in the National Széchényi Library of Budapest. One of the most prominent documents within the Codex (f. 154a) is the Funeral Sermon and Prayer ... It is an old handwritten Hungarian text dating to 1192-1195. Its importance of the Funeral Sermon comes from that it is the oldest surviving Hungarian, and Uralic, text ... One of the five illustrations within the Codex shows the burial of Jesus. ... the display shows remarkable similarities with the Shroud of Turin: that Jesus is shown entirely naked with the arms on the pelvis, just like in the body image of the Shroud of Turin; that the thumbs on this image appear to be retracted, with only four fingers visible on each hand, thus matching detail on the Turin Shroud; that the supposed fabric shows a herringbone pattern, identical to the weaving pattern of the Shroud of Turin; and that the four tiny circles on the lower image, which appear to form a letter L, `perfectly reproduce four apparent "poker holes" on the Turin Shroud', which likewise appear to form a letter L. The Codex Pray illustration may [sic does] serve as evidence for the existence of the Shroud of Turin prior to 1260–1390 AD, the alleged fabrication date established in the radiocarbon 14 dating of the Shroud of Turin in 1988 ..."[56].]Bela III (r. 1172–1196), who had spent six years (1163–1169) as a young man in the imperial court at Constantinople[57]. So during Bela's reign there were strong cultural links between Constantinople and Hungary[58]. The codex contains four pen and ink drawings (see my 11Jan10) pertaining to the death of Jesus[59]. The first panel depicts the Crucifixion; the second shows the descent from the Cross; the third panel is divided into two, the top section showing the body of Jesus laid out on a cloth for burial, and the lower section depicting the arrival of the holy women on Easter morn who find an angel at the empty tomb; and the fourth panel is that of the glorified Christ[60]. Of particular relevance to the Shroud is the third drawing with two scenes, one above the other, of the deposition of Jesus' body from the cross and His entombment[61]. Together they share the following eight features in common with Shroud: 1. Jesus' wrists are crossed, right over left, at the groin; 2. He is naked; 3. there is a red mark over Christ's right eyebrow where the reversed `3' bloodstain is on the Shroud; 4. Christ's hands lack thumbs; 5. His burial sheet is long and bi-fold; 6. He has a sarcophagus with crosses and zigzags imitating the herringbone weave of the Shroud; 7. the sarcophagus has angular blood flows matching those on the arms of the man on the Shroud; and 8. there are two sets of tiny circles which match the sets of L-shaped `poker holes' on the Shroud[62]. These eight correspondences between those drawings in the Pray Codex and the Shroud are together conclusive proof that the 12th century artist of the Pray Codex had seen the Shroud[63] in 1192-95, at least 65 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date[64]. So the Pray codex `poker holes' are the final nail in the coffin of the carbon-dating result[65]. In 1993 Nobel prize-winning geneticist Jérôme Lejeune (1926-1994) was granted a rare private viewing of the Pray codex in Budapest[65a]. In an interview a month later he said:

"But the most extraordinary image of all is to be found in the lower foreground of the image: an angel is pointing out the Shroud to the pious women who had come to the tomb with perfumed oils on Easter morning. Well, in that design the four `L'-shaped holes are perfectly visible, the holes the Turin Shroud still has today. And they can even be seen, perfectly superimposable, on the back of the cloth, which is also represented in the design. It is absolutely unthinkable that a painter could design, without ever having seen it, an image showing holes of the same size and in the same place (and which are the result of the rather anomalous folds of the cloth so that the holes can be superimposed one on the other) as the holes that the Turin Shroud still has today. In short, the Turin Shroud existed before 1192. This is a definitive historic certainty. There can be no further discussion on the point ... There is no doubt about it. The Carbon 14 dating by the three laboratories does not give the age of the Shroud of Turin. Their dating (1260-1390) is in disaccord with the historic certainty that between 1100 and 1200 a painter saw all the details of the Shroud today kept in Turin, including the burn holes which are not at all interesting from the artistic point of view"[65b].So the Pray Codex alone proves beyond reasonable doubt that the Shroud of Turin is the Shroud of Constantinople and therefore existed from at least 944 [see "944b"], more than three centuries before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date[66]![G]

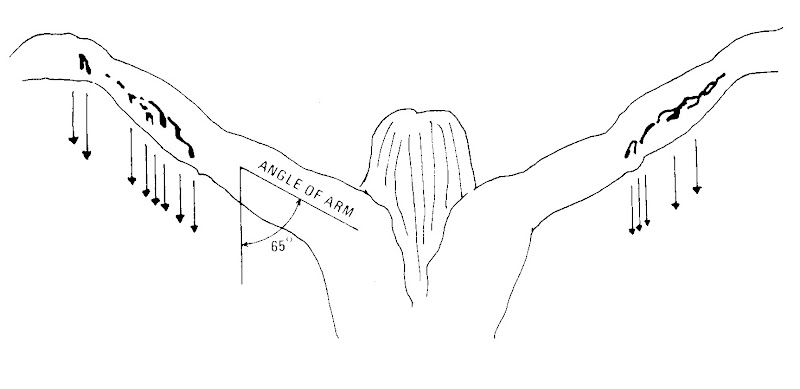

1181 A champlevé enamel panel which forms part of the altar in the Klosterneuberg monastery, near Vienna, completed in 1181 by Nicholas of Verdun (1130–1205)[67]. As can be seen below, Jesus is being

[Above (enlarge): Entombment of Jesus, 1181, by Nicholas of Verdun, Klosterneuburg Abbey, Vienna[68].]

wrapped in a long burial shroud, with His hands crossed over His loins, right over left, awkwardly at the wrists, exactly as on the Shroud[69]! Yet this was 79 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud![H]

1171: Chronicler William of Tyre (c.1130–1186), as Archbishop of Tyre[70], accompanied a state visit of King Amaury I, aka. Amalric I, (r. 1163-1174) of Jerusalem to Emperor Manuel I Comnenus (1118–1180) in Constantinople[71]. William recorded his party being shown "the most precious evidences of the passion of our Lord Jesus Christ" including "the shroud" [sindon][72]. However William did not mention an image on the shroud, but this can be explained either by him only seeing its reliquary within which was the folded cloth[73] or the light being too dim for him to distinguish the Shroud's faint image. [I]

c. 1150 The Christ Pantocrator ("Ruler of all"[74]) mosaic in the apse of Cefalu Cathedral, Sicily[75] is among the most recent of many such

[Above: (enlarge): Christ Pantocrator, Cefalu Cathedral, Sicily[76].

"... if the radiocarbon dating is to be believed, there should be no evidence of our Shroud [before 1260]. The year 1260 was the earliest possible date for the Shroud's existence by radiocarbon dating's calculations. Yet artistic likenesses of Jesus originating well before 1260 can be seen to have an often striking affinity with the face on the Shroud ... Purely by way of example we may cite from the twelfth century the huge Christ Pantocrator mosaic that dominates the apse of the Norman Byzantine church at Cefalu, Sicily ..."[77].]works in the Byzantine tradition,which depict a Shroud-like, long-haired, fork-bearded, front-facing likeness of Christ[80]. But at c.1150 it is still over a century before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud[81]. It has 14 out of 15 Vignon markings (see Revised #2)[82], including a triangle between the nose and the eyebrows, concave cheeks, asymmetrical and pronounced cheekbones, each found on the Shroud, and a double tuft of hair where the reversed `3' bloodstain is on the Shroud[83]. This means the artist was working from the face on the Shroud, copying each feature carefully, even though he did not understand what some of them were, for example the open, staring eyes are actually closed in photographic negative on the Shroud[84].[J]

c. 1150 A Christ Pantocrator fresco, dating back to the twelfth century, in the rupestrian (cave) Church of St. Nicholas in Castelrotto, Italy[85].

[Above (enlarge): Christ Pantocrator centre panel of fresco between Mary and John the Baptist (see here), in the twelfth century cave church in Castelrotto, Italy[86].]

Jesus' face is Shroud-like, rigidly forward-facing with Vignon markings including a forked beard, open staring eyes, a wisp of hair where the reversed `3' bloodstain is in the Shroud, and a triangle between the nose and the eyebrows[87].[K]

1140 "The Song of the Voyage of Charlemagne to Jerusalem" (known

[Above: The front cover of a 1965 French reprint of the poem, "Le Voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople"[88]:

"Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne or Voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople (Pilgrimage of Charlemagne or Charlemagne's Voyage to Jerusalem and Constantinople) is an Old French chanson de geste (epic poem) dealing with a fictional expedition by Charlemagne and his knights. The oldest known written version was probably composed around 1140"[89].]by various names in French, including "Chanson du Voyage de Charlemagne à Jerusalem"[90] and "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne"[91]), is an Old French epic poem about a fictional expedition by Emperor Charlemagne the Great (c.742-814) and his knights, composed around 1140[92]. But although imaginary it bears historical testimony to the existence of the Shroud, in that it reflects the accounts given by pilgrims at that time[93]. In it the Emperor asks the Patriarch of Jerusalem if he has any relics to show him, and the Patriarch replies:

"I shall show you such relics that there are not better under the sky: of the Shroud of Jesus which He had on His head, when He was laid and stretched in the tomb ..."[94].While this contains an inaccuracy in that the Shroud was not in Jerusalem in Charlemagne's time (c.742-814) but continuously in Edessa from 544 to 944[see "544" and "944b"], the word "Shroud" is the Old French equivalent of "sindon"[95], the Greek word used in the Gospels for Jesus' burial shroud (see above). Also the pilgrim French Bishop Arculf had reported seeing a shroud in Jerusalem in c.670, but this cannot have been the Shroud [see "670a"]. So The Voyage of Charlemagne evidently reflects these mistaken pilgrims' reports of a shroud in Jerusalem in the Early Middle Ages. Moreover this Old French word for sindon, presumably is the same sydoines used by Robert de Clari over 60 years later (see above). So this is evidence that in 1140, well over a century before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud, it was common knowledge that the burial sindon of Jesus existed, upon which He had been laid stretched out in the tomb, and which had then covered His head![L]

c.1130-1140 An English-born Norman monk[96] Ordericus Vitalis (1075 - c.1142), in his History of the Church (Historia Ecclesiastica), written by 1140[97], when he came to the 1098 capture of Edessa in the First Crusade (1095-1099)[98], Ordericus updated the Abgar V story, that:

"Abgar the ruler reigned at Edessa; the Lord Jesus sent him a sacred letter and a beautiful linen cloth he had wiped the sweat from his face with. The image of the Saviour was miraculously imprinted on to it and shines out, displaying the form and size of the Lord's body to all who look on it"[99].A cloth which displays "the form and size of the Lord's body" is clearly a full-length sheet, not a mere towel as in the original Abgar story[100]. As with Gervase of Tilbury (see above) about 80 years later, this is one of a number of altered version of the Abgar story which substituted for Jesus' imprinting his face onto a cloth, Jesus laying his whole body upon a cloth in order to produce an image of his whole figure[101]. In attempting to update the Abgar story with the new information that the Edessa cloth has not only an image of Jesus' face, but also of His whole body, Ordericus contradicted himself, since Jesus' pressing His face to a cloth would not thereby imprint His whole body onto that cloth[102]. Since Ordericus' History was widely read throughout France and England, this may be the earliest generally known reference to the Shroud in Western Europe[103].[M]

Pre-1130 Vatican Library codex (Vati. Lib. Codex 5696, fol. 35)[104] has an update of a sermon of Pope Stephen III (c.720-772), originally delivered in 769[105]. The original 8th century sermon mentioned only the Edessa towel with a miraculous image of Jesus' face imprinted on it [see "769"][106]. But sometime before 1130[107] an unknown copyist had interpolated into Pope Stephen's sermon, additional sayings of Jesus to King Abgar V of Edessa:

"For this same mediator between God and men [Jesus], in order that in all things and in every way he might satisfy this king [Abgar] spread out his entire body on a linen cloth that was white as snow. On this cloth, marvellous as it is to see or even hear such a thing, the glorious image of the Lord's face, and the length of his entire and most noble body, has been divinely transferred ..."[italics Wilson's]. [108]The early twelfth century copyist had new information that in Constantinople the image of Edessa was now known to be not only of Jesus' face but also a "white linen" sheet upon which "the length" of Jesus' "entire body" had been "divinely transferred" [109]! Again this can only be the Shroud in Constantinople, at least 130 years before its earliest 1260 radiocarbon date! [N]

Continued in the next part #9 of this series.

Notes

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to extract or quote from any part of it (but not the whole post), provided the extract or quote includes a reference citing my name, its title, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

2. Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY, p.7 & pl.3b; Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London, p.308. [return]

3. Damon, P.E., et al., 1989, "Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin," Nature, Vol. 337, 16 February, pp.611-615, 611. [return]

4. McCrone, W.C., 1999, "Judgment Day for the Shroud of Turin," Prometheus Books: Amherst NY, pp.1,141,178,246; Wilson, 1998, p.7. [return]

5. Latendresse, M., 2012, "A Souvenir from Lirey," Sindonology.org. [return]

6. Wilson, 2010, pp.221-222. [return]

7. Ibid. [return]

8. Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY, pp.67, 165, 190; Meacham, W., 2005, "The Rape of the Turin Shroud: How Christianity's Most Precious Relic was Wrongly Condemned and Violated," Lulu Press: Morrisville NC, pp.110-111; Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition, pp.172-173. [return]

9. Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London, p.3; Wilson, I., 1996, "Jesus: The Evidence," [1984], Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, Revised, p.134; Wilson, 1998, pp.125, 141; Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London, p.113; Wilson, 2010, p.108. [return]

10. Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition, p.160; Wilson, 1991, p.152; Wilson, I., 1994, "News From Home and Abroad," BSTS Newsletter, No. 38, August/September, p.5; "Medieval wall paintings," Winchester Cathedral, n.d. [return]

11. Wilson, 1998, p.139. [return]

12. "Reflecting back on this week of poems of the Passion," The Pocket Scroll blog, 19 April 2014. (no longer online) [return]

13. Wilson, 1979, p.160; Wilson, 1998, p.139. [return]

14. Wilson, 1998, p.139. [return]

15. "Gervase of Tilbury," Wikipedia, 19 November 2016. [return]

16. "Otia Imperialia," Wikipedia, 18 June 2017. [return]

17. Green, M., 1969, "Enshrouded in Silence: In search of the First Millennium of the Holy Shroud," Ampleforth Journal, Vol. 74, No. 3, Autumn, pp.319-345; Wilcox, R.K., 1977, "Shroud," Macmillan: New York NY, p.95; Wilson, 1979, p.159; Drews, R., 1984, "In Search of the Shroud of Turin: New Light on Its History and Origins," Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham MD, p.48; Wilson, 1991, p.153; Wilson, 1998, pp.139, 144, 255n20; Guscin, M., 2009, "The Image of Edessa," Brill: Leiden, Netherlands & Boston MA, pp.206-207. [return]

18. Scavone, D.C., "The History of the Turin Shroud to the 14th C.," in Berard, A., ed., 1991, "History, Science, Theology and the Shroud," Symposium Proceedings, St. Louis Missouri, June 22-23, 1991, The Man in the Shroud Committee of Amarillo, Texas: Amarillo TX, pp.171-204, 195. [return]

19. Wilson, 1979, p.159; Wilson, 1998, p.144. [return]

20. Scavone, D.C., 1989a, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA, p.89. [return]

21. Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, p.8; Fanti, G. & Malfi, P., 2015, "The Shroud of Turin: First Century after Christ!," Pan Stanford: Singapore, pp.57-58. [return]

22. Iannone, 1998, p.126; Guerrera, 2001, p.8; Fanti & Malfi, 2015, p.57. [return]

23. Adams, F.O., 1982, "Sindon: A Layman's Guide to the Shroud of Turin," Synergy Books: Tempe AZ, p.71; Iannone, 1998, pp.126-127; Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY, pp.122-123; de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London, p.175. [return]

24. Iannone, 1998, p.127; de Wesselow, 2012, pp.175-176; Fanti & Malfi, 2015, pp.57-58. [return]

25. Wilson, 1991, pp.156-157; de Wesselow, 2012, p.176. [return]

26. de Wesselow, 2012, pp.177-178. [return]

27. Currer-Briggs, N., 1984, "The Holy Grail and the Shroud of Christ: The Quest Renewed," ARA Publications: Maulden UK, p.158; Currer-Briggs, N., 1988a, "The Shroud and the Grail: A Modern Quest for the True Grail," St. Martin's Press: New York NY, p.45. [return]

28. Wuenschel, E.A., 1954, "Self-Portrait of Christ: The Holy Shroud of Turin," Holy Shroud Guild: Esopus NY, Third printing, 1961, pp.58-59. [return]

29. "File:Icône Sainte Face Laon 150808.jpg, Wikimedia Commons, 13 September 2008. Translated from French by Google. [return]

30. de Riedmatten, P., 2008, "The Holy Face of Laon," BSTS Newsletter, No. 68, December. [return]

31. Currer-Briggs, 1984, p.21. [return]

32. "Pope Urban IV," Wikipedia, 21 August 2016. [return]

33. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.45; Wilson, 1991, pp.47, 78. [return]

34. Wilson, I., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London, p.110F. [return]

35. Wilson, 1991, p.78. [return]

36. Currer-Briggs, 1984, p.60; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.158; Wilson, 1991, p.136; Antonacci, 2000, p.131. [return]

37. Wilson, 1979, pp.114-115; Wilson, 1998, pp.150-151. [return]

38. Currer-Briggs, N., 1995, "Shroud Mafia: The Creation of a Relic?," Book Guild: Sussex UK, p.56. [return]

39. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.58. [return]

40. Wilcox, 1977, p.97; Wilson, I., 1983, "Some Recent Society Meetings," BSTS Newsletter, No. 6, September/December, p.13; Currer-Briggs, 1984, p.21; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.157; Currer-Briggs, N., 1988b, "Dating the Shroud - A Personal View," BSTS Newsletter No. 20, October, pp.16-17; Wilson, 1991, p.47; Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.205; Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK, p.108. [return]

41. Wuenschel, 1954, pp.58-59; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.158; Oxley, 2010, p.108. [return]

42. Wilson, 1991, p.78. [return]

43. Currer-Briggs, 1995, p.56. [return]

44. Currer-Briggs, 1995, pp.56-57]. [return]

45. Wilson, 1979, pp.167, 257; Adams, 1982, p.71; Scavone, 1991, p.195; Scavone, 1989a, p.89; Wilson, 1991, p.155; Wilson, 1998, pp.145, 272; Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN, p.58; Antonacci, 2000, p.123; Guerrera, 2001, p.7; Tribbe, 2006, pp.25, 29; Oxley, 2010, p.40; Wilson, 2010, p.185; de Wesselow, 2012, p.176. [return]

46. Wilson, 1979, pp.167-168, 257; Scavone, 1989a, p.89; Scavone, 1989b, pp.320-321; Wilson, 1991, p.155; Wilson, 1998, p.145; Wilson, 2010, p.185; de Wesselow, 2012, p.176. [return]

47. Wilson, 1991, p.155; Wilson, 1998, p.145; de Wesselow, 2012, p.176. [return]

48. Scavone, 1989b, p.321; Wilson, 1991, p.155; Wilson, 1998, p.272. [return]

49. Scavone, 1989a, p.89. [return]

50. Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R., 1871, "A Lexicon: Abridged from Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon," Clarendon Press: Oxford, Reprinted 1935, pp.1, 545, 410. [return]

51. Wilson, 1991, p.155; Wilson, 1998, p.145; de Wesselow, 2012, pp.176-177, 181. [return]

52. de Wesselow, 2012, p.176, 380n11. [return]

53. de Wesselow, 2012, p.177. [return]

54. Berkovits, I., 1969, "Illuminated Manuscripts in Hungary, XI-XVI Centuries," Horn, Z., transl., West, A., rev., Irish University Press: Shannon, Ireland, p.19; Wilson, 1979, p.160; "Pray Codex," Wikipedia, 12 April 2017. [return]

55. Wilson, 1991, p.151. [return]

56. "Pray Codex," Wikipedia, 12 April 2017. [return]

57. de Wesselow, 2012, p.178. [return]

58. de Wesselow, 2012, p.178. [return]

59. Guerrera, 2001, p.104. [return]

60. Guerrera, 2001, p.104. [return]

61. Berkovits, 1969, p.19; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.115. [return]

62. Wilson, 1986, p.114; Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1996, "The Enigma of the Shroud: A Challenge to Science," Scerri, L.J., transl., Publishers Enterprises Group: Malta, pp.163-164; Maloney, P.C., 1998, "Researching the Shroud of Turin: 1898 to the Present: A Brief Survey of Findings and Views," in Minor, M., Adler, A.D. & Piczek, I., eds., 2002, "The Shroud of Turin: Unraveling the Mystery: Proceedings of the 1998 Dallas Symposium," Alexander Books: Alexander NC, p.33; Wilson, 1998, pp.146-147; Scavone, D.C., "Greek Epitaphoi and Other Evidence for the Shroud in Constantinople up to 1204," in Walsh, B., ed., 2000, "Proceedings of the 1999 Shroud of Turin International Research Conference, Richmond, Virginia," Magisterium Press: Glen Allen VA, pp.196-211, 196-197; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.116; Guerrera, 2001, pp.104-105; Scavone, D.C., "Underscoring the Highly Significant Historical Research of the Shroud," in Tribbe, 2006, p.xxvi; Oxley, 2010, pp.37-38; Wilson, 2010, pp.183-184, 300; de Wesselow, 2012, pp.178-181. [return]

63. Wilson, 1998, p.147; Scavone, 2000, pp.196-197; Guerrera, 2001, p.106; Whiting, B., 2006, "The Shroud Story," Harbour Publishing: Strathfield NSW, Australia, pp.92; Oxley, 2010, p.38; de Wesselow, 2012, p.181. [return]

64. Iannone, 1998, p.154; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.115; Marino, J.G., 2011, "Wrapped up in the Shroud: Chronicle of a Passion," Cradle Press: St. Louis MO, p.53. [return]

65. Guerrera, 2001, p.106; de Wesselow, 2012, p.183. [return]

65a. Lejeune, J., in Pacl, S.M., 1993, "All those carbon 14 errors," 30 Days, No 9, 1993, in Shroud News, No 80, December, pp.3-8, 6. [return]

65b. Lejeune, 1993, p.6-7. [return]

66. de Wesselow, 2012, pp.178, 183. [return]

67. Wilson, 2010, p.182. [return]

68. Wilson, I., 2008, "II: Nicholas of Verdun: Scene of the Entombment, from the Verdun altar in the monastery of Klosterneuburg, near Vienna," British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, No. 67, June. [return]

69. Wilson, 2010, pp.182-183. [return]

70. "William of Tyre," Wikipedia, 19 June 2017. [return]

71. Wilson, 1979, p.165; Iannone, 1998, pp.120-121; Wilson, 1998, p.271; Guerrera, 2001, p.6; Tribbe, 2006, p.25; de Wesselow, 2012, p.177. [return]

72. Wilson, 1979, pp.165-166; Scavone, 1989b, p.321; Iannone, 1998, p.121; Wilson, 1998, p.271; Tribbe, 2006, p.25; de Wesselow, 2012, p.177. [return]

73. Bulst, W., 1957, "The Shroud of Turin," McKenna, S. & Galvin, J.J., transl., Bruce Publishing Co: Milwaukee WI, p.8. [return]

74. Ruffin, 1999, p.110; Zodhiates, S., 1992, "The Complete Word Study Dictionary: New Testament," AMG Publishers: Chattanooga TN, Third printing, 1994, pp.1093-1094. [return]

75. Wilson, 1979, p.102; Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY, p.82; Wilson, 1998, p.141; Antonacci, 2000, p.126. [return]

76. "File:Master of Cefalu 001 Christ Pantocrator adjusted.JPG," Wikipedia, 15 June 2010. [return]

77. Wilson, 1998, p.141. [return]

80. Wilson, 1986, p.105; Wilson, 1998, p.141. [return]

81. Wilson, 1986, p.104. [return]

82. Wilson, 1979, p.105; Maher, 1986, p.82. [return]

83. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.193. [return]

84. Wilson, 1979, p.105. [return]

85. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.193. [return]

86. Martino Miali, 2014, "Mottolo (Taranto). Church of St. Nicholas: fresco depicting Christ Almighty between Our Lady and St. John the Baptist. Photo by Martino Miali," Bridge Puglia & USA. [return]

87. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.193. [return]

88. Aebischer, P., 1965., "Le voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople," Librairie Droz: Amazon.com. [return]

89. "Le Pèlerinage de CharlemagneLe Pèlerinage de Charlemagne," Wikipedia, 29 February 2016. [return]

90. Beecher, P.A., 1928, "The Holy Shroud: Reply to the Rev. Herbert Thurston, S.J.," M.H. Gill & Son: Dublin, p.147. [return]

91. "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne," Wikipedia, 27 February 2013. [return]

92. Ibid. [return]

93. Beecher, 1928, p.147. [return]

94. Ibid. [return]

95. Adams, 1982, p.17. [return]

96. Wilson, 1998, pp.144, 270. [return]

97. Adams, 1982, p.26; Ruffin, 1999, p.58; "Orderic Vitalis: The Historia Ecclesiastica," Wikipedia, 25 June 2017. [return]

98. Scavone, 1989a, p.89. [return]

99. Wilcox, 1977, p.95; Adams, 1982, p.26; Drews, 1984, p.47; Wilson, 1986, p.114; Wilson, 1991, pp.152-153; Wilson, 1998, pp.144, 270; Ruffin, 1999, p.58; Wilson, 2010, p.176. [return]

100. Iannone, 1998, p.120. [return]

101. Scavone, 1991, p.195. [return]

102. Guscin, 2009, p.206. [return]

103. Currer-Briggs, 1984, p.21. [return]

104. Wilson, 1979, p.257. [return]

105. Scavone, 1989a, p.88; Scavone, 1989b, p.318. [return]

106. Scavone, 1989a, p.88; Scavone, 1989b, p.318. [return]

107. Wilson, 1979, p.158; Adams, 1982, p.26; Scavone, 1989b, p.318; Wilson, 1991, p.152. [return]

108. Wilcox, 1977, p.97; Wilson, 1991, p.152. See also Wilson, 1979, p.158, 257; Adams, 1982, p.26. [return]

109. Scavone, 1989a, p.89. [return]

Posted 21 June 2017. Updated 7 July 2025.