This is the entry, "Locations of the Shroud: Turin 1578-1694," in my Turin Shroud Encyclopedia. Previous entries in this series were: "Locations: Lirey c.1355-Chambéry 1471," and "Locations: Chambéry 1471-Turin 1578." I am working through the topics in the entry, "Shroud of Turin, expanding on them.

[Index] [Previous: Locations: Chambéry 1471-Turin 1578] [Next: Locations: Turin 1694-1918]

Introduction. This is the third of a five-part series of entries which will briefly trace the locations of the cloth today known as Shroud of Turin, from its first appearance in undisputed history (see previous) at Lirey, France in c.1355, to its current location since 1578 (apart from short periods due to wars) in or around St John the Baptist Cathedral, Turin, Italy. It is partly based on my 2012 post, "The Shroud's location."

Chambéry-Turin (1578-1604). On 14 September 1578 the Shroud arrived in Turin, carried at the head of a triumphal procession by four Archbishops. Three weeks later Cardinal Charles Borromeo (1538–84), Archbishop of Milan, arrived after his pilgrimage on foot from Milan, which was originally to have been over the Alps to Chambéry. But Duke Emmanuel Philibert I of Savoy (1528–80) had seized this as an excuse to bring the Shroud from Chambéry to Turin which he had established as Savoy's capital. The Cardinal was given an informal private viewing of the Shroud where it was being kept, in the Duke's small Chapel of San Lorenzo adjacent to the his palace gardens, over which the

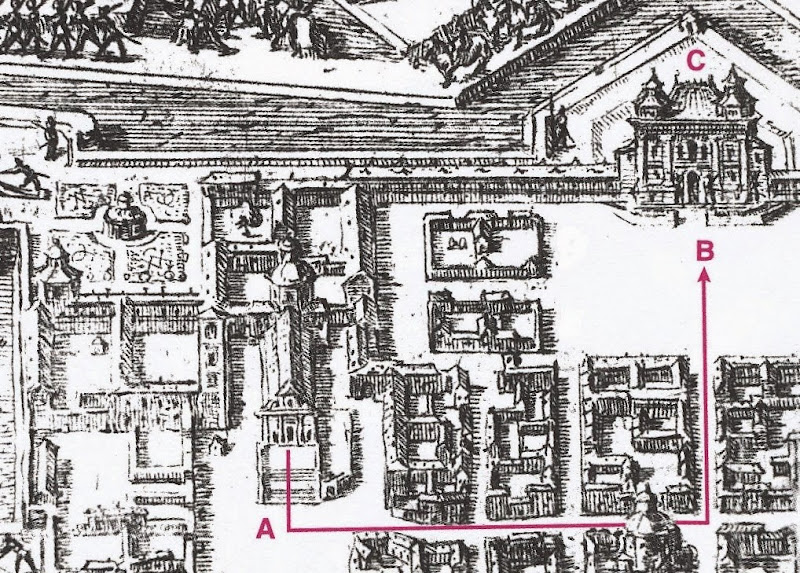

[Right (enlarge): Extract from a 1618-19 plan[1] showing the location (A) of the Duke's private Chapel of San Lorenzo, in which the Shroud was kept from 1578 until a new Chapel of the Holy Shroud (D) would be built between Turin's Cathedral of St John the Baptist (C) and the ducal Palace complex (E).]

current Church of San Lorenzo was built. It was on the Feast Day of St. Lawrence (San Lorenzo), 10 August, in 1557 (see previous) that Duke Emmanuel Philibert defeated the French at the Battle of St. Quentin. The Cardinal expressed his concern that such an important relic was being kept in a small chapel and offered the cathedral, but the Duke demurred as that would imply church jurisdiction over the Shroud. The next day the Cardinal and his retinue were given an official private viewing in Turin Cathedral followed by a public viewing in the the Piazza Castello, Turin's main square (see print below). In 1580 Duke Emmanuel Philibert died in Turin, and was succeeded by his only child, Duke Charles Emmanuel I (1562–1630). In 1582 Cardinal Borromeo had walked a second pilgrimage from Milan to venerate the Shroud in Turin and to mark that occasion the Shroud was first exhibited to the Cardinal and his retinue in a new, larger (but still small) chapel and

[Above (enlarge): Extract from a c.1640 map of Turin[2] by Giovenale Boetto (c.1603-78), showing the Shroud's processional route from the Cathedral (A) to the Piazza Castello (B) in front of the Castle (C). The domed structure upper left is believed to be the larger chapel where the Shroud was kept c.1580-7.]

later publicly in the cathedral and, when the crowds became too great, in the Piazza Castello (see below). But the Cardinal was still not happy

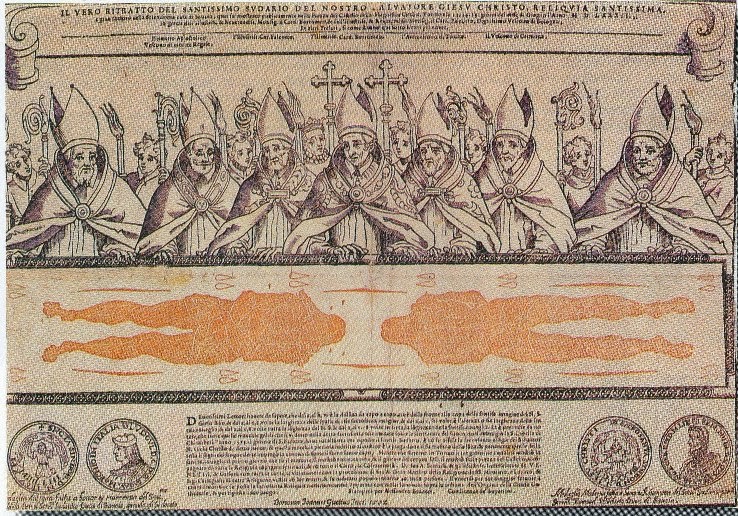

[Above (enlarge): Print depicting the public exposition of the Shroud in Turin on 13-15 June 1582[3], to mark the second pilgrimage by Cardinal Charles Borromeo (centre cleric holding the Shroud) to venerate the Shroud in Turin.]

that the Shroud was being kept in a small chapel. The new Duke Charles Emmanuel I agreed that the Shroud should be kept in the Cathedral until a permanent private Savoy Chapel of the Holy Shroud was built between the Palace and the Cathedral - see (D) above. Borromeo's idea was for the Shroud to be mounted above the Cathedral's high altar and to be continuously visible, to obviate it being damaged by continually folding and unfolding it. In 1585 the Duke married Catherine Michelle of Spain (1567–97), a daughter of King Philip II of Spain (1527–98) and Elisabeth de Valois (1545–68) a daughter of King Henry II of France (1519–59). Although Duchess Catherine only lived to age 31, she bore 10 children, 9 of which survived to adulthood. Their second son, Victor Amadeus I (1587–1637) would become the next Duke of Savoy. Cardinal Borromeo died in 1584, and in 1587 the Duke carried through with his idea (albeit less grandiosely) by locating the Shroud in Turin Cathedral, displayed continuously on a shrine supported by four wooden columns over the cathedral's high altar.

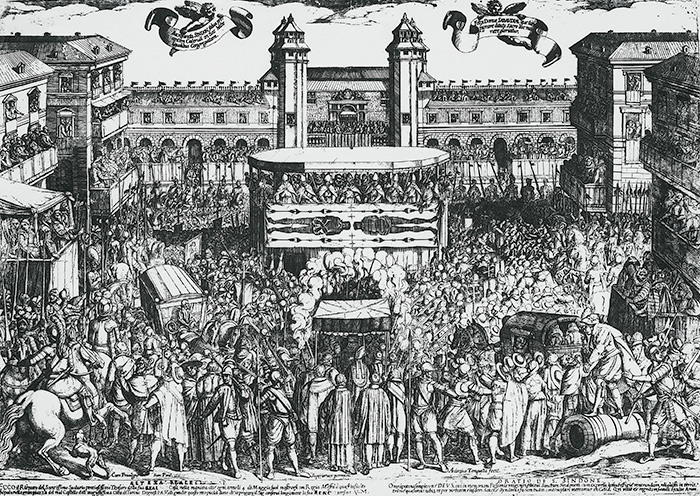

Turin (1587-1630). In 1588 Charles Emmanuel I occupied the adjoining Marquisate of Saluzzo, which had been annexed by France following the deposition and death of the last Marquis of Saluzzo, Gian Gabriel I (1501-48). A war with France ensued, until the Treaty of Lyon (1601), in which Saluzzo went to Savoy in exchange for Savoy territories in France. In 1602, Charles Emmanuel attempted a night raid on the city of Geneva to eradicate its Protestants, but it failed with the Savoy army forced to retreat and many Savoyards killed. In 1604, the Shroud was enclosed in a new 4 foot (~1.2 m) long wooden casket, decorated with silver and gold relief plaques of the instruments of the Passion, and rolled up around a velvet-covered staff. This casket would remain the Shroud's container until the 1990s. Every 4th of May, the Feast Day of the Holy Shroud, the Shroud was exhibited publicly in the Piazza Castello. An engraving by Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630) of the

[Above (enlarge): "Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630), View of the Piazza del Castello, Turin, during the ostension of the Holy Shroud, 1613"[4].]

4 May 1613 exposition captures their immense popularity. The Shroud was shown publicly in the Piazza Castello in 1620 to mark the marriage between the Duke Charles Emmanuel I's eldest surviving son, and future Duke, Victor Amadeus with Princess Christine de Bourbon (1606–63) a daughter of the late King Henry IV of France (1553–1610) and sister of the current King Louis XIII (1601–43). In 1630 Duke Charles Emmanuel I died and was succeeded as Duke by his eldest surviving son Victor Amadeus I.

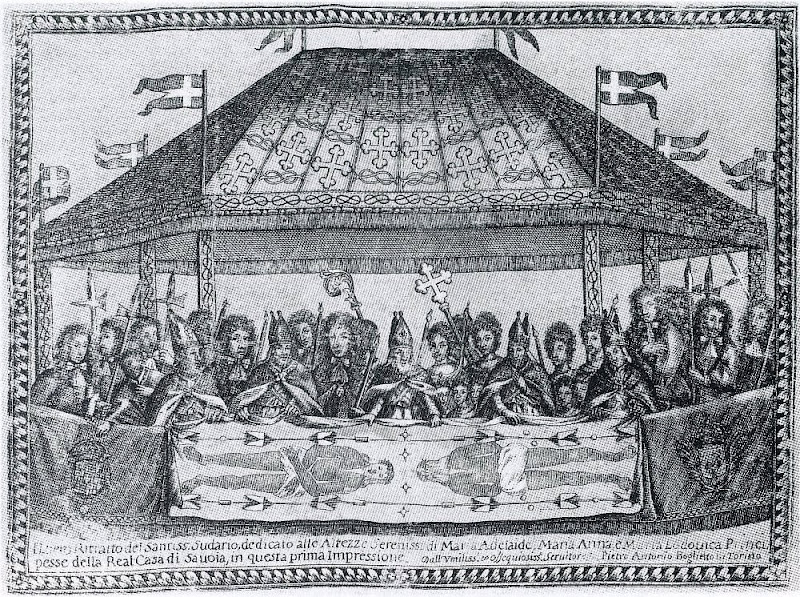

Turin (1630-94). In 1637 Victor Amadeus I died and was succeeded as Duke by his 5 year-old son, Francis Hyacinth (1632–8), with his mother dowager Duchess Christine acting as regent. But Francis in turn died a year later, and was succeeded as Duke by his 4 year-old brother Charles Emmanuel II (1634-75) with Christine continuing to act as regent for him. But two of Victor Amadeus' brothers, Maurice (1593–1657) and Thomas (1596–1656) disputed Christine's regency and her French influence and so with Spanish support they started the Piedmontese Civil War (1639-41). However, Christine was victorious due to French military support. In April 1663 Duke Charles Emmanuel II married Christine's niece Françoise d'Orléans (1648–64). But Christine died in December 1663 and Françoise died childless a week later in January 1664. Charles married in 1665 Marie Jeanne Baptiste de Savoie-Nemours (1644-1724), a descendant of Duke Emmanuel Philibert's brother Jacques (1531–85). In 1666 their only child and future Duke, Victor Amadeus II (1666–1732) was born. In 1668 the architect Guarino Guarini (1624–83) was appointed to construct the Chapel of the Holy Shroud, between the Royal Palace and Turin cathedral, as envisaged in 1618-19 by Duke Charles Emmanuel II (see above). Duke Charles Emmanuel II died in 1675 and was succeeded as Duke by the 9 year-old Victor Amadeus II, with his mother dowager Duchess Marie acting as regent. On 6 May 1684 Duke Victor Amadeus II married Anne Marie de Orléans (1669–1728). She was a daughter of Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (1640–1701), who was a son of King Louis XIII of France, and Henrietta Stuart (1644-70), who was a daughter of the late King Charles I of England (1600-49). The marriage took place in Chambéry, and two days later the newlyweds entered Turin, celebrated by a public exposition of the Shroud (see below). However,

[Above (enlarge): Painting by Pieter Bolckmann (1640-1705)[5] of the public exposition of the Shroud in Turin's Piazza Castello on 8 May 1684, to mark the wedding of Duke Victor Amadeus II and Anne Marie de Orléans].

[Above (enlarge): Etching on silk, c. 1690, by Pietro Antonio Boglietto[6] depicting five bishops holding the Shroud at its abovementioned 1684 public exposition.]

Duchess Anne did not bear a son who survived to adulthood until 1701 (as we shall see).

Continued in the entry, "Locations of the Shroud: Turin 1694-1918."

Notes

1. Scott, J.B., 2003, "Architecture for the Shroud: Relic and Ritual in Turin," University of Chicago Press: Chicago & London, p.63. [return]

2. Scott, 2003, pp.66, 225. [return]

3. Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London, plate 30b. [return]

4. "The Origins of the Shroud of Turin," Medievalists.net, 24 October 2014. [return]

5. Wilson, 2010, plate 31a. [return]

6. Scott, 2003, p.239. [return]

References

• Jones, S.E., 2015, "Savoy Family Tree," Ancestry.com.au (members only).

• Scott, 2003, pp.62-71.

• Wilson, I., 1996, "A Calendar of the Shroud for the years 1509-1694," British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, No. 44, November/ December.

• Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY, pp.290-293.

• Wilson, 2010, pp.246, 260-264, 304-305.

Posted: 8 April 2015. Updated: 11 October 2025.

9 comments:

This is a comment I received yesterday by email. I have posted it under this my latest post and will respond to it shortly.

--------------------------------

Hello,

My name is ... and I’m currently researching the Turin Shroud for my extended project qualification at school. I came across your blog and it has been one of the most helpful websites I’ve found, so thank you for your dedication to the Shroud!

I did try to post this as a comment on the blog, but for some reason I wasn’t able to. I was reading your post about the poker holes in the shroud, and noticed that you also mentioned the Pray Codex as I’ve seen a lot of other researchers have pointed out. At first I was convinced that the existence of the holes on the Pray Codex meant the Shroud must have dated to an earlier time as the artist of the Pray Codex must have copied that holes formation from it. However, I’ve also noticed that one seems to have considered the (admittedly unlikely) possibility that the holes in the shroud could have been modelled on the Pray Codex, presumably by the artist who many claim forged the shroud. I was just wondering whether I’ve missed something that means this can’t be the case, as I really would like to believe that the painting must have been based on the shroud!

Many thanks in advance for anything you can tell me,

[...]

>Hello,

>

>My name is ... and I’m currently researching the Turin Shroud for my extended project qualification at school.

Great! I have often wondered if my blog is useful to students such as yourself.

>I came across your blog and it has been one of the most helpful websites I’ve found, so thank you for your dedication to the Shroud!

Thank YOU.

>I did try to post this as a comment on the blog, but for some reason I wasn’t able to.

I don't know why. I haven't changed my blog's "Who can comment" setting. I have checked and it is still "Anyone - includes Anonymous Users."

>I was reading your post about the poker holes in the shroud,

I presume you mean my 2013 post, "The Shroud of Turin: 2.6. The other marks (2): Poker holes."

>and noticed that you also mentioned the Pray Codex as I’ve seen a lot of other researchers have pointed out.

The Pray Codex is mentioned in that post above, and it is also covered in my 2012 post, "My critique of `The Pray Codex,' Wikipedia, 1 May 2011."

>At first I was convinced that the existence of the holes on the Pray Codex meant the Shroud must have dated to an earlier time as the artist of the Pray Codex must have copied that holes formation from it.

You were right the first time.

>However, I’ve also noticed that one seems to have considered

Newcomers to the Shroud sometimes think that they have discovered something about it that no one else has considered. But that is highly unlikely, given that the Shroud has been the subject of intense criticism by Shroud sceptics for over a century.

>...the (admittedly unlikely) possibility that the holes in the shroud could have been modelled on the Pray Codex, presumably by the artist who many claim forged the shroud.

Ian Wilson and Mark Guscin are two Shroud pro-authenticist authors who consider, and refute, the general Shroud sceptic argument that a 13th-14th century forger went around museums and art galleries (as French biologist/artist Paul Vignon did in the early 20th century), noting marks-in-common on Byzantine artworks dating back to the 6th century (the "Vignon markings"), and included those in his Shroud forgery.

[continued]

[continued]

But problems with that include:

1) The forger would have had to travel thousands of kilometres visiting museums and art galleries, in the 13th-14th century when travel was very difficult and very hazardous.

2) But public museums and art galleries didn't exist in 13th-14th century, as artworks were in private collections or churches, and even the latter were not generally viewable by the public.

3) Europe was wracked by wars in those centuries, including "The Hundred Years War" (1337-1453), which particularly devastated France.

4) Europe was also ravaged by the Black Death from 1347 to the 18th century, which killed between 30% and 60% of the population.

5) The former Byzantine Empire, including Constantinople, had been subsumed by the Islamic Ottoman Empire (1299-1566).

6) The Shroud has features which were unknown in the 14th century, such as photographic negativity, arterial and venous blood circulation, serum halos surrounding blood clots, etc.

7) Why would a forger go to so much time, effort and expense in a gullible age which would have been (and WAS) satisfied with far less?

8) A forger who went to that degree of time, effort and expense to forge the Shroud would have sold his forgery for a lot of money to someone RICH. But Geoffroy I de Charny (c.1300-56), the first undisputed owner of the Shroud, was POOR. He had to request funding from the King of France to build his modest wooden church at Lirey.

9) And having made ONE Shroud, the forger would have made MORE, since the public and clergy did not care that other churches had their own `original' of the same relic.

[continued]

[continued]

>I was just wondering whether I’ve missed something that means this can’t be the case, as I really would like to believe that the painting must have been based on the shroud!

In addition to those general problems of the forgery theory, additional problems of the forger incorporating the "poker holes" on the Pray Codex, include:

10) The ink drawings which symbolically depict the Shroud, including its L-shaped "poker holes," are inside a codex which is written in Old Hungarian, which a 13th-14th century forger would be most unlikely to understand and so be interested in.

11) Why would a forger who had been collecting Vignon markings be bothered with the Pray Codex's "poker holes" which are not in any Byzantine artwork?

12) The Pray Codex was compiled at Boldva monastery in Hungary between 1192-95. That is 65 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud. And the drawings within the Codex, which depict the "poker holes" (and 7 other unique features on the Shroud, according to agnostic art historian Thomas de Wesselow), must be even older than that. Therefore the Pray Codex drawings alone refute the 1260-1390 radiocarbon date of the Shroud.

13) The Pray Codex was discovered in 1770 by György Pray, presumably in the archives of the University of Nagy-Szombat in Slovakia where Pray was then a professor of theology. The codex and its drawings had presumably been there unrecognised since 1285 when the Boldva monastery was destroyed by the Mongols and the monks fled. The unknown, hypothetical, medieval forger of the Shroud, in addition to his other `superhuman' museum and art gallery (which didn't then exist) travels, would have had to travel to Hungary or Slovakia, discover the Codex written in Old Hungarian, and the drawings inside it, copy 8 features on those drawings including the "poker holes," and incorporate them also into his hypothetical Shroud forgery.

Shroud sceptics can respond with the glib answer that the forger incorporated the Vignon markings and Pray Codex features in his forgery, but no Shroud sceptic has actually proposed a COMPREHENSIVE forgery theory which plausibly explains in detail HOW and WHEN the forger did it (let alone WHY), museum by museum, art gallery by art gallery, marking by marking. If a Shroud sceptic had attempted to develop such a comprehensive forgery theory, he must have quietly given up, when he realised its IMPLAUSIBILITY (if not IMPOSSIBILITY).

>Many thanks in advance for anything you can tell me,

[...]

I hope this has helped you to realise that you were indeed right the first time!

Stephen E. Jones

---------------------------------

Reader, if you like this my The Shroud of Turin blog, and you have a website, could you please consider adding a hyperlink to my blog on it? This would help increase its Google PageRank number and so enable those who are Google searching on "the Shroud of Turin" to more readily discover my blog. Thanks.

(Sent this as a reply to your last comment but I can't see it so I'm not sure if it sent) Thank you so much for such a detailed response to my question, I'm now re-convinced that the painting must have been based on the shroud!

Also, on another topic, I don't suppose you've covered the pollen traces that were found on the shroud in your post anywhere have you? I'm making my way through them all so I'm sure I'll stumble across it eventually if you have, but I wondered if I could quickly get your opinion on something I read earlier. Someone claimed that, because it can't be disputed that the shroud has not left Europe since the time that the carbon dating results place it's creation at, the fact that pollen from Jerusalem can be found on it shows the shroud must have existed outside of Europe at an earlier date. Would you consider this sufficient evidence to dispute the carbon dating, or do you feel the pollen could have come in contact with the shroud some other way? (I need as many opinions from researchers as possible for my epq!)

Ella May

>Thank you so much for such a detailed response to my question, I'm now re-convinced that the painting must have been based on the shroud!

Great!

>Also, on another topic, I don't suppose you've covered the pollen traces that were found on the shroud in your post anywhere have you?

To the right of my blog is my "Index to this blog's posts." Working your way through that by year and date you can see there are posts about pollen, including:

"22-Aug-14: Lynne Milne's `A Grain of Truth: How Pollen Brought a Murderer to Justice, (2005)"

"26-Nov-08: Did Max Frei misidentify Carduus argentatus Shroud pollen as Gundelia tournefortii?

>I'm making my way through them all so I'm sure I'll stumble across it eventually if you have,

See above. You could also try Googling "pollen Stephen Jones" (without the quotes). I also found another post on the Pray Codex:

"Jan 11-Jan-10: The Pray Manuscript"

>but I wondered if I could quickly get your opinion on something I read earlier.

Because I could become bogged down responding to comments (it takes a LOT more time answering a question than asking it), and my priority is posting blog posts, I have a policy (see below) of normally only one comment per individual per blog post.

Also my time is taken up daily scanning and word-processing Shroud Spectrum International for Barrie Schwortz's Shroud.com archive; and I have just started scanning and word-processing the 118 issues of Rex Morgan's Shroud News, for a new Shroud.com archive.

So if you have any further comments please space them out, one per blog post.

>Someone claimed that, because it can't be disputed that the shroud has not left Europe since the time that the carbon dating results place it's creation at, the fact that pollen from Jerusalem can be found on it shows the shroud must have existed outside of Europe at an earlier date.

Agreed.

[continued]

[continued]

>Would you consider this sufficient evidence to dispute the carbon dating, or do you feel the pollen could have come in contact with the shroud some other way? (I need as many opinions from researchers as possible for my epq!)

Max Frei himself (and others) have answered that in ">Shroud Spectrum International, which you should be able to find by a Google search. His points were:

1) It would be fantastically improbable for pollen to blow all the way from the Middle East and land on the Shroud in Europe, in quantities that are far greater than European pollen.

2) Especially considering that the Shroud in Europe has almost all that time been folded or rolled up in its various reliquaries, and only exposed to the open air at comparatively brief expositions.

3) Also the wind patterns wouldn't blow pollen to blow in any quantity from the Middle East to Europe.

However, Shroud pollen is a contentious issue. The problem is that Frei died before completing his research , and the sticky tape he used to seal in his pollen makes it difficult (if not impossible) for palynologists to determine their microscopic features to correctly identify their species. There is also the problem that most palynologists would likely be unconsciously prejudiced against the Shroud's authenticity and a fair evaluation of the Shroud's pollen would be problematic.

Moreover, Frei's pollens have been superseded by Prof. Avinoam Danin's identification of plant images on the Shroud, one of which, Chrysanthemum coronarium can be seen even over the Internet . See:

"22-Nov-08: Re: There is compelling evidence it is the burial cloth of Christ, or a man crucified during that time #2"

"06-Apr-13: The Shroud of Turin: 2.6. The other marks (4): Plant images"

"30-Mar-15: "D": Turin Shroud Dictionary: Danin, Avinoam"

Stephen E. Jones

----------------------------------

MY POLICIES Comments are moderated. Those I consider off-topic, offensive or sub-standard will not appear. Except that comments under my latest post can be on any Shroud-related topic without being off-topic. I normally allow only one comment per individual under each one of my posts.

Hello,

My name is Ayla Garrigó and I work at the Shroud of Turin Expo in San Antonio. We just wanted to let you know a little bit about us and what we do (www.shroudexpo.com) and also, inform you that Dr. John P. Jackson (one of the leading scientists that worked on the Shroud) is coming to San Antonio for the first time to do a conference on May 2nd. There's more information about it in our web page and Facebook page. Thank you and God bless you.

ayla

>My name is Ayla Garrigó and I work at the Shroud of Turin Expo in San Antonio. We just wanted to let you know a little bit about us and what we do (www.shroudexpo.com) ... There's more information about it in our web page and Facebook page. Thank you and God bless you.

Glad to be of help publicising the expo.

Stephen E. Jones

Post a Comment