This is my "Problems of the forgery theory #3." For more information about this series, see part #1. As mentioned in part #1, this "Problems of the forgery theory" series will help me write, Chapter 18 (previously 19), "Problems of the forgery theory," of my book in progress, "Shroud of Turin: Burial Sheet of Jesus!" The in-line references which clutter these posts are actually for that chapter and will be unobtrusive numbered endnotes, and less of them, in the book.

[Previous #2][Next #4]

© Stephen E. Jones

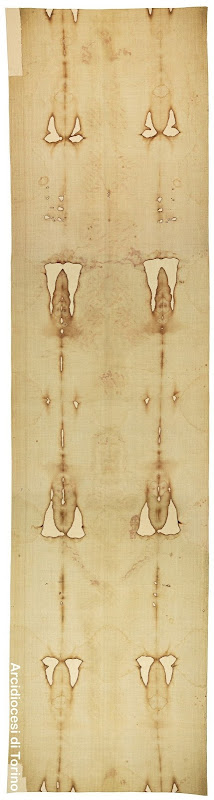

The man's image (Ch. 5). Not painted See 11Jul16. We have seen that

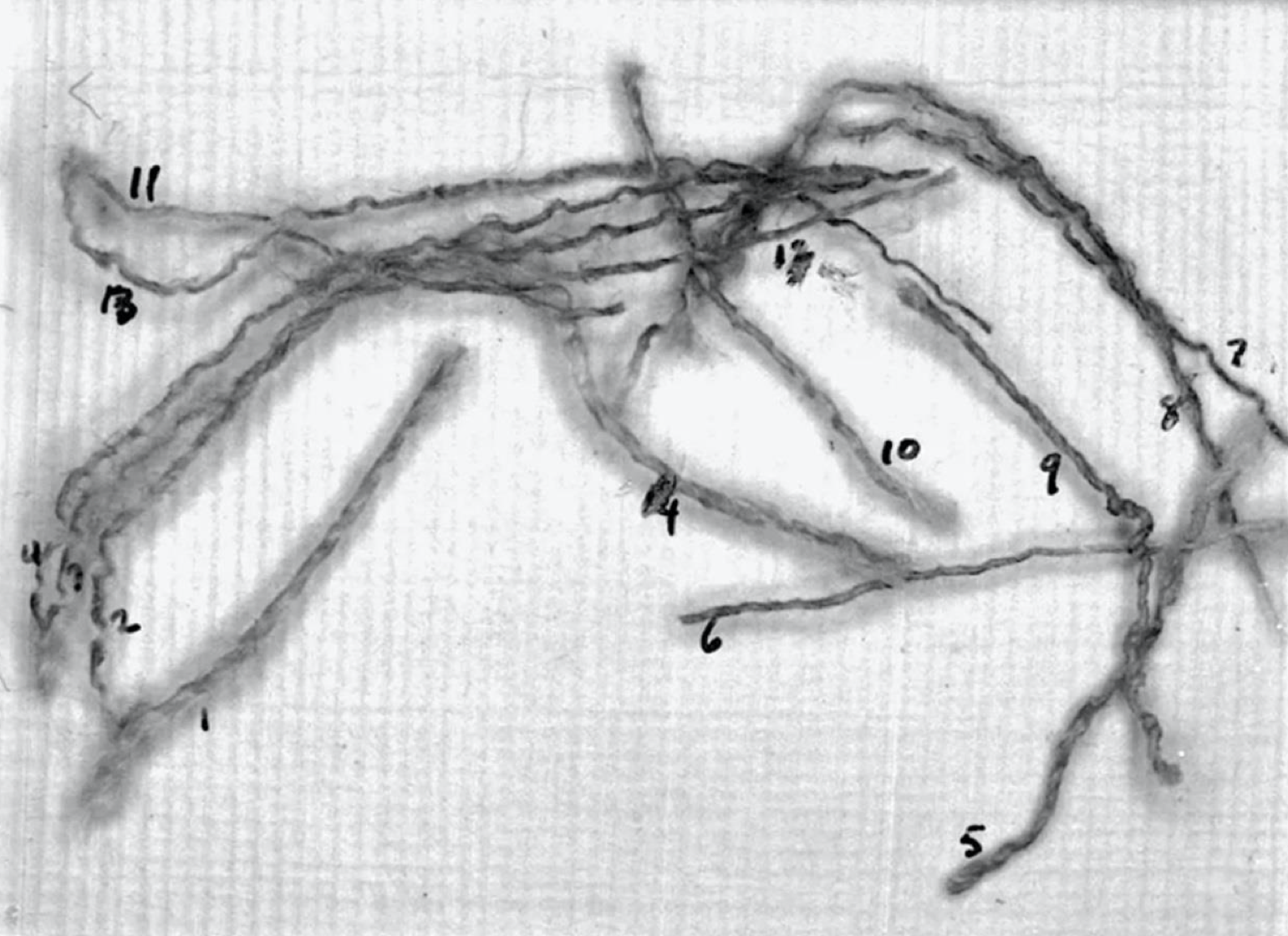

[Right (enlarge): Photo-micrograph taken by optical engineer Kevin Moran (1934-2019) of 15 microns (15 thousandths of a millimetre) diameter Shroud fibres attached to one of Max Frei (1913–83)'s Shroud sticky tapes[MK99, 8]. The boundaries between the image (yellow) and non-image parts of each fibre are only about 1 micron (1 thousandth of a millimetre) wide. No human artist/forger can paint, etc., with such precision. The yellow colour of the image fibres is due to a physical change in the flax: dehydrative oxidation and conjugation of cellulose[10 Jul24].]

leading Shroud sceptic Joe Nickell (1944-) admitted in 1987 that the Shroudman's image was not painted[NJ87, 99-100]. But why would a medieval forger not have painted his forgery of the Shroud? Was not earlier leading Shroud sceptic Walter McCrone (1916-2002) correct that a medieval forger would have simply painted the Shroud[MW99, 122]? If the Shroud is not a painting, then Bishop Pierre d'Arcis (r. 1377-95) was wrong that the Shroud was "cunningly painted" by a confessed forger in c. 1355[WI79, 266-267]! This is already a fatal blow to the entire forgery theory?

Negative How could a medieval forger depict the Shroudman's image

[Above (enlarge): Secondo Pia (1855-1941)'s 1898 negative photograph of the Shroud face[HFW], which because it is a photographic positive, proved that the Turin Shroud image is a photographic negative[MP78, 26-27; OG85, 46-47; AM00, 34-35]. And this is just the face of what was Pia's full-length, front and back, Shroud photograph [see 07May16]!].

as a photographic negative, when the concept of photographic negativity was unknown until the invention of photography in the 1820s[SH81, 31]?:"Negative photography has its beginnings all the way back in 33 AD [sic 30]. The first-ever possibly negative image is considered to be the Turin Shroud, an image of a deceased man’s body imprinted into linen cloth ... The fact that some areas of the image are dark where they should be light and vice versa has made some scholars deduce that this is the first example of negative photography in history. After the Turin Shroud, there is almost no evidence of negative photography until the 19th century. Nicephore Niepce [1765-1833], a French inventor and scientist, is often credited with creating the first negative photograph in 1826. Titled `View From the Window at Le Gras,' Niepce captured this image on a piece of metal using a camera obscura and light-sensitive silver salts scrubbed on the surface. It took several days of exposure to sunlight for the silver salts to leave an impression on the metal surface, but eventually, a negative image was produced" (my emphasis)[SK19].He would have no way of checking that his positive image would correctly appear as a photographic negative[JJ77, 85; CJ84, 34; OG85, 72; WI98, 22; TF06, 182] (assuming he could even conceive of those terms). And why would a medieval forger depict the man's image as a photographic negative when neither he, nor his contemporaries, could appreciate it[GM69; OG85, 72; TF06, 182, 234]?

Three-dimensional How could a medieval forger encode the Shroud-

[Right (enlarge): "The Shroud image's three-dimensional character-istics, as revealed by the VP-8 Image Analyzer in February 1976"[WI10, pl. 8a]. Only the Shroud's frontal image is three-dimensional because the dorsal (back) image was in direct contact with the Shroud[BJ01, 167] (see Jackson's "Cloth Collapse Theory").]

man's image with three-dimensional information[CB78, 238; HA81, 48; SH81, 69; SR82, 7; BM95, 22; IJ98, 44; AM00, 39, 47; OM10, 218]? And in negative[MR86, 53; IJ98, 70] (see above)! When true perspective, the correct of a three-dimensional object on a two dimensional surface[PT22], was first discovered in 1415 by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446)[PGW]. But the Shroudman's image is not an artistic representation of three-dimensionality: it actually is three-dimensional[RTB]! A medieval forger would have to encode three dimensional information into the Shroud image by adjusting the intensity levels of his work to everywhere correspond to actual cloth-body distance[JJ77, 85]! The three-dimensional information is encoded, uniquely, in any negative, flat, two-dimensional Shroud photograph[CT96, 15]. All other photographs appear distorted under a VP-8 Image Analyzer[CB78, 238; MR86, 53; AM00, 38, 78; WS00, 36]. All attempts to replicate the Shroud's three-dimensional image failed the VP-8 Image Analyzer test[SH81, 108; SH90, 32; RC99, 99; GV01, 65; AM00, 61, 73; OM10, 216, 253-254]. Why would a medieval forger have encoded three-dimensional information into his Shroud image, when it was only discovered to be, more than six centuries later[IJ98, 44; WS00, 36; TF06, 182; WI10, 22]?

Superficial How could a medieval forger depict the Shroud man's

[Left (enlarge): STURP's 1978 transmitted light photograph of the front half of the Shroud, in which the light source is behind the suspended cloth so only the light transmitted through it is seen. The scorches and waterstains from the 1532 fire, and the bloodstains, have penetrated the thickness of the cloth and so can be clearly seen. But the body image has almost completely disappeared, demonstrating that the image of the man on the Shroud is superficial, only one fibre deep[11Nov16].]

image, with medieval materials and technology, lying only on the very top exposed fibers of the weft (widthwise) threads, leaving the unexposed fibers of the threads of the weave unchanged[AA0c, 15]? With no evidence of cementation of the body image fibrils to one another, no capillarity or penetration of the color below the top surface fibrils on the crowns of the weave[HA81, 47]? The superficiality characteristic is violated by forgery theories which involve the application of a colouring medium, because the image could not be encoded only on the topmost fibrils of the linen[AM00, 36, 78].

Non-directional How could, and why would, a medieval forger depict

[Right (enlarge)[AM16]: The computer screen of STURP's Don Lynn (1932-2000) and Jean Lorre (1945-2005), which showed that the Shroudman's image was non-directional. See 16Apr22].]

the Shroudman's image non-directionally[CB78, 237; HJ83, 137; CJ84, 53; DR84, 16; BM95, 22; AM00, 37-38; DT12, 136]? And therefore could not have been formed by the application of colouring matter[CB78, 237; HJ83, 137; CJ84, 53; BM95, 22; AM00, 38; DT12, 136]. But had to have appeared all at once, like a photograph[RTB].

No outline How could, and why would, a medieval forger depict the

[Left (enlarge)[LM10]: Extract of front trunk and thighs area of the Shroud man's image. As can be seen, there is no outline of the image. Readers can verify this for themselves by clicking on this (or any) image area of Shroud Scope and continually enlarging it by clicking on that part of the image, until maximum magnification is reached. They will find that as the image is enlarged it becomes more diffuse and no outline ever appears - because there isn't one! See 11Jun16]

Shroudman's image with no outline[BA34, 50; WI79, 22; DR84, 16; NJ87, 98-99; CN88, 33; CN95, 12; IJ98, 17; WI98, 218; WS00, 38; OM10, 3]? Which it would have if it was painted[WI79, 22; DR84, 16; NJ87, 98; CN88, 33; IJ98, 156, 178; WI98, 21; WS00, 38]. Why did Nicholas Mesarites (c. 1163-aft.1216), the Keeper of the Byzantine Empire's relic collection, after the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, recall that in 1201 the collection included "the sindon [which] wrapped the un-outlined (Gk. aperilepton), naked dead body [of Christ]"[SD89, 320-321; TF06, 193; DT12, 176]? This can only be the Shroud, 59 years before its earliest 1260 radiocarbon date and 154 years before it first appeared in 1355, in undisputed history, at Lirey, France!

No style. Why does the Shroudman's image not fit the artistic style of

[Right (enlarge):"This painting of Christ by Simone Martini [c. 1284–1344] is an underdrawing for a fresco[TF24], executed in sinopia (red ochre) c.1340. Walter McCrone [1916-2002] suggested that Simone, or an artist like him, might have painted the Shroud using a similar technique, but the idea is implausible. Like all medieval artists, Simone represents Christ in an idealized manner, and his brushwork is always evident"[DT12, pl. 33]. And unlike the man's image on the Shroud, Martini, like all visual artists[SVW], had a distinctive individual artistic style, which "contrasted with the sobriety and monumentality of Florentine art, and is noted for its soft, stylized, decorative features, sinuosity of line, and courtly elegance"[SMW]. See 05Sep16]

the fourteenth, or any, century[BP53, 31; BW57, 31-32; GM98, 114; IJ98, 4, 156-157, 180; CT99, 291-292; WM86, 4; WS00, 32]? If the Shroud has a style, it is "completely true to nature"[BA34, 15], but how could a medieval forger have that?

Notes

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to quote from any part of this post (but not the whole post), provided it includes a reference citing my name, its subject heading, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

Bibliography

AC02. Adler, A.D. & Crispino, D., ed., 2002, "The Orphaned Manuscript: A Gathering of Publications on the Shroud of Turin," Effatà Editrice: Cantalupa, Italy.

AA0c. Adler, A.D., 2000c, "Chemical and Physical Aspects of the Sindonic Images," in AC02, 10-27.

AM00. Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY.

AM16. Antonacci, M., 2016, "Test The Shroud: At the Atomic and Molecular Levels," Forefront Publishing Company: Brentwood TN, p.7.

BA34. Barnes, A.S., 1934, "The Holy Shroud of Turin," Burns Oates & Washbourne: London.

BJ01. Bennett, J., 2001, "Sacred Blood, Sacred Image: The Sudarium of Oviedo: New Evidence for the Authenticity of the Shroud of Turin," Ignatius Press: San Francisco CA.

BM95. Borkan, M., 1995, "Ecce Homo?: Science and the Authenticity of the Turin Shroud," Vertices, Duke University, Vol. X, No. 2, Winter, 18-51.

BP53. Barbet, P., 1953, "A Doctor at Calvary," [1950], Earl of Wicklow, transl., Image Books: Garden City NY, Reprinted, 1963.

BW57. Bulst, W., 1957, "The Shroud of Turin," McKenna, S. & Galvin, J.J., transl., Bruce Publishing Co: Milwaukee WI.

CB78. Culliton, B.J., 1978, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin Challenges 20th-Century Science," _Science_, Vol. 201, 21 July, 235-239.

CJ84. Cruz, J.C., 1984, "Relics: The Shroud of Turin, the True Cross, the Blood of Januarius. ..: History, Mysticism, and the Catholic Church," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN.

CN88. Currer-Briggs, N., 1988, "The Shroud and the Grail: A Modern Quest for the True Grail," St. Martin's Press: New York NY.

CN95. Currer-Briggs, N., 1995, "Shroud Mafia: The Creation of a Relic?," Book Guild: Sussex UK.

CT96. Case, T.W., 1996, "The Shroud of Turin and the C-14 Dating Fiasco," White Horse Press: Cincinnati OH.

CT99. Cahill, T., 1999, "Desire of the Everlasting Hills: The World before and after Jesus," Nan A. Talese/Doubleday: New York NY.

DR84. Drews, R., 1984, "In Search of the Shroud of Turin: New Light on Its History and Origins," Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham MD.

DT12. de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London.

GM69. Green, M., 1969, "Enshrouded in Silence: In search of the First Millennium of the Holy Shroud," Ampleforth Journal, Vol. 74, No. 3, Autumn, 319-345.

GM98. Guscin, M., 1998, "The Oviedo Cloth," Lutterworth Press: Cambridge UK.

GV01. Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL.

HA81. Heller, J.H. & Adler, A.D., 1981, "A Chemical Investigation of the Shroud of Turin," in AC02, 34-57.

HFW. "Holy Face of Jesus," Wikipedia, 7 July 2024.

IJ98. Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY.

JJ77". Jackson, J.P., Jumper, E.J., Mottern, R.W. & Stevenson, K.E., ed., 1977, "The Three Dimensional Image on Jesus' Burial Cloth," in Stevenson, K.E., ed., "Proceedings of the 1977 United States Conference of Research on The Shroud of Turin," Holy Shroud Guild: Bronx NY.

LM10. Extract from Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002 Vertical," Sindonology.org.

MK99. Moran, K.E., 1999, "Optically Terminated Image Pixels Observed on Frei 1978 Samples," Shroud.com, 1-10

MP78. McNair, P., 1978, "The Shroud and History: Fantasy, Fake or Fact?," in Jennings, P., ed., "Face to Face with the Turin Shroud," Mayhew-McCrimmon: Great Wakering UK.

MR86. Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY.

MW99. McCrone, W.C., 1999, "Judgment Day for the Shroud of Turin," Prometheus Books: Amherst NY.

NJ87. Nickell, J., 1987, "Inquest on the Shroud of Turin," [1983], Prometheus Books: Buffalo NY, Revised, Reprinted, 2000.

OG85. O'Rahilly, A. & Gaughan, J.A., ed., 1985, "The Crucified," Kingdom Books: Dublin.

OM10. Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK.

PGW. "Perspective (graphical)," Wikipedia, 25 December 2023.

PT22. "Perspective Coursework Guide," Tate, 31 May 2022.

RTB. Reference(s) to be provided.

RC99. Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN.

SD89. Scavone, D., "The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople: The Documentary Evidence," in Sutton, R.F., Jr., 1989, "Daidalikon: Studies in Memory of Raymond V Schoder," Bolchazy Carducci Publishers: Wauconda IL, 311-329.

SH81. Stevenson K.E. & Habermas G.R., 1981, "Verdict on the Shroud: Evidence for the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ," Servant Books: Ann Arbor MI.

SH90. Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1990, "The Shroud and the Controversy," Thomas Nelson: Nashville TN.

SK19. Sommerfield, K., "History of Negative Photography," Aperture: Kodak, 15 November 2019.

SR82. Schwalbe, L.A. & Rogers, R.N., 1982, "Physics and Chemistry of the Shroud of Turin: A Summary of the 1978 Investigation," Analytica Chimica Acta, No. 135, 3-49.

SMW. "Simone Martini," Wikipedia, 12 September 2023.

SVW. "Style (visual arts)," Wikipedia, 7 June 2024.

TF06. Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition.

TF24. "The frescoes of the Church of Avignon Notre Dame des Doms, scene: Christ Pantocrator with angels, fragment, 1341 by Simone Martini," Arthive, 2024.

WI79. Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition.

WM86. Wilson, I. & Miller, V., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London.

WI98. Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY.

WI10. Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London.

WS00. Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London.

Posted 27 July 2024. Updated 4 November 2024.