TWELFTH CENTURY (1)

© Stephen E. Jones[1]

This is the split part #12, "Twelfth century (1)" of my "Chronology of the Turin Shroud: AD 30 - present" series. See also 29Mar14. For more information about this series see part #1, "1st century and Index." Emphases are mine unless otherwise indicated. I decided to split this my "Chronology of the Turin Shroud: Twelfth Century" (1101-1200) into two parts 1101-1150 (1) and 1152-1200 (2), and insert a summary of the c. 1150 Chartres Cathedral stained glass windows [see 29Nov18a], into this first part (1). [See below and "c.1150"]. Part (2) is at 20Dec18.

[Index #1] [Previous: 11th century #11] [Next: 12th century (2) #13]

12th century (1) (1101-1150).

[Above (enlarge). Telephotograph of the "Crucifixion panel," in the "Window of the Passion and Resurrection," Chartres Cathedral, emailed to me by Prof. Roberto Falcinelli[2]. In this "The Crucifixion" panel, within the "Window of the Passion and Resurrection" (see "c. 1150" below), Jesus is depicted with a realistic reversed `3' or epsilon (ε) bloodflow on his forehead [see also 29Nov18b], and also a nail wound in his right wrist [see below and 29Nov18c], both exactly as on the Shroud!].]

1119 Formation of the Knights Templar[3]. The Order of Knights Templar was founded by noblemen from north-eastern France to defend Christianity against the Saracens at the beginning of the twelfth century[4]. It reached the height of its power and wealth during the thirteenth century and was finally suppressed in 1307 by King Philip IV of France (r.1285-1314)[5] [See "1307"]. In 1314 France's two leading Templars,

[Right (enlarge): Minia- ture (1380) depiction of the burning at the stake on 18 March 1314, of Templars Jacques de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney on an island (Île des Juifs - Isle of the Jews) in the Seine River, Paris[6].]

Jacques de Molay (c.1243–1314) and Geoffroi de Charney (c.1240–1314), were burned at the stake for recanting their confessions extracted under torture and proclaiming their, and the Templar Order's, innocence of the false charges brought by King Philip IV[7, 8, 9]. See my 09May15 that this Geoffroi de Charney was the great-uncle of Geoffroy I de Charny (c. 1300–1356), the first undisputed owner of the Shroud [See "1314"] Pro-authenticist historian Ian Wilson theorised that the Templars acquired

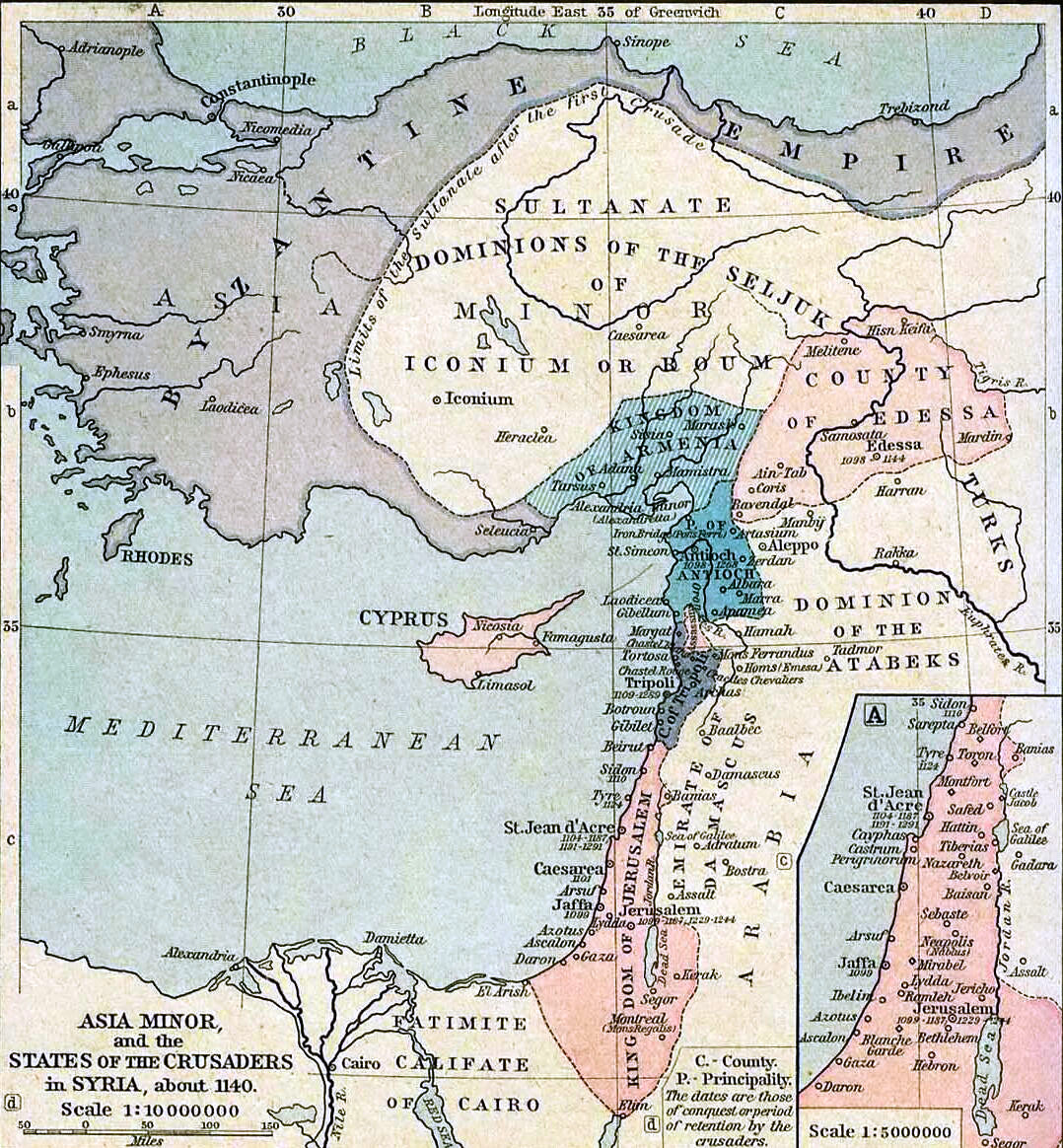

[Above (enlarge): Composite map illustrating Ian Wilson's theory that the Shroud was taken from Constantinople in 1204 to Acre, in today's Israel, and from there to France after 1291[10]. Wilson no longer holds that theory (see below).]

the Shroud after it was looted from Constantinople in 1204 by soldiers of the Fourth Crusade[11], and took it to their fortress at Acre[12]. Then after the Fall of Acre in 1291 the Templars took the Shroud to France and hid it in their network of fortresses and castles[13]. However, there is little evidence for Wilson's Templar theory[14] (see "1185") and at the 2012 Valencia Shroud conference, Wilson announced that he no longer held it[15].

Pre-1130 Before 1130, Vatican Library codex 5696, folio 35[16], is a Latin update of an original Greek[17] Easter Friday sermon by Pope Stephen III (r.768-772), delivered in 769[18]. [see "769"]. Stephen's original 8th century sermon quoted Jesus' supposed letter in response to Edessa's King Abgar V's request for healing [see "50"]:

"Since you wish to look upon my physical face, I am sending you a likeness of my face on a cloth ..."[19]The twelfth-century Vatican version contains an interpolation (in italics):

"Since you wish to look upon my physical face, I am sending you a likeness of not only of my face but of my whole body divinely transformed on a cloth ..."[20]Clearly the twelfth century copyist knew that the Edessa cloth now in Constantinople had an image not only of Jesus' face, but of His entire body, and he updated Pope Stephen's 769 sermon according to the new information he had[21]. [see "950" [11May14]

c.1130 An English-born Normandy monk Ordericus Vitalis (1075–c.1142)[22], in his History of the Church, written by 1130, when he came to an important event near his own day, the capture of Edessa in the First Crusade [see "1095], he retold the Abgar story, but with a new twist:

"Abgar the ruler reigned at Edessa; the Lord Jesus sent him a sacred letter and a beautiful linen cloth he had wiped the sweat from his face with. The image of the Saviour was miraculously imprinted on to it and shines out, displaying the form and size of the Lord's body to all who look on it"[23].As with the above Pope Stephen III's sermon interpolation, this is an altered version of the Abgar story which substituted an image of Jesus' face, with an image of Jesus' whole body, imprinted onto a cloth[24].

1140a "The Song of the Voyage of Charlemagne to Jerusalem" (known by  various names in French, including "Chanson du Voyage de Charlemagne à Jerusalem"[25], or "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne"[26]), is an Old French epic

various names in French, including "Chanson du Voyage de Charlemagne à Jerusalem"[25], or "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne"[26]), is an Old French epic

[Left: The front cover of a 1965 reprint of the poem[27]. The oldest known written version was probably composed around 1140"[28].]

poem about a fictional expedition by Emperor Charlemagne the Great (c.742-814) and his knights, composed around 1140[29]. Although imaginary it bears historical testimony to the existence of the Shroud at the time, in that it reflects the accounts then given by pilgrims[30]. In it the Emperor asks the Patriarch of Jerusalem if he has any relics to show him, and the Patriarch replies:

"I shall show you such relics that there are not better under the sky: of the Shroud of Jesus which He had on His head, when He was laid and stretched in the tomb ..."[31].While this contains an inaccuracy in that the Shroud was not in Jerusalem in Charlemagne's time (c.742-814) but continuously in Edessa from 544 to 944[see "544"] and ["944b"]. See also ["670a"] where the pilgrim French Bishop Arculf had reported seeing a shroud in Jerusalem in c.670, but this cannot have been the Shroud [see below]. So The Voyage of Charlemagne evidently reflects genuine but mistaken pilgrims' reports of a shroud in Jerusalem in the Early Middle Ages. The word for "Shroud" in The Voyage of Charlemagne is the Old French equivalent of "sindon"[32], the Greek word, used in the Gospels for Jesus' burial shroud (Mt 27:59; Mk 15:46; Lk 23:53)[33]. Moreover this Old French word (presumably sydoines) is the same word used by crusader Robert de Clari (1170-1216) of the shroud with "the figure of Our Lord on it" that he saw ~63 years later in Constantinople in 1203[34] (see future "1203"). So this is evidence that in 1140, over a century before the earliest, 1260, radiocarbon date of the Shroud, it was common knowledge that the burial shroud of Jesus existed, upon which He had been laid stretched out in the tomb, and which had then covered His head!

1140b Peter the Deacon (c. 1107-c.1159), a monk of Monte Cassino, Italy[35], claimed that in 1140 he had seen the Shroud in Jerusalem[36]. From his description of the ceremony, Peter's belief that this was Jesus' burial shroud was shared by the authorities in Jerusalem[37], as they were in Arculf's day [see above] and "670a"]. But the Shroud was continuously in Constantinople from 944 [see "944b"] to 1204 [see "1204"]. The shroud that Peter and Arculf saw in Jerusalem was only eight feet long[38], so it cannot have been the Shroud which is over fourteen feet long[39]. However, it could have been the Besançon shroud which had a painted frontal image only[40] and was eight feet long[41]. See future ["c. 1350"] and ["1794"].

1144 Edessa, having been captured in 1098 by Christian forces under Baldwin of Boulogne (1058-1118), who became the first ruler of the Crusader state, the County of Edessa [see "1095"], fell to Turkish Muslim forces[42] in the 1146 Siege of Edessa[43]. The bones

[Right (enlarge)[44]. A stone Christian cross over a lion's head in a former fountain in modern Sanliurfa (ancient Edessa), which has survived the almost complete eradication of Edessa's Christian history since the Muslim recapture of Edessa in 1144. The lion was the symbol of the Abgar dynasty[45], which ceased ruling over Edessa after Abgar VIII's death in 212 [see "212"].]

of Abgar V and Addai (Thaddeus) were thrown out of their coffins in the Church of St John the Baptist and scattered, but were retrieved by Christians and reinterred in the Church of St Theodore[46].

1146 After a temporary Crusader recapture under the former Count of Edessa, Joscelin II (1113-59), Edessa was again taken by the Turks in 1146[47]. This time there was much bloodshed[48], with more than 30,000 Christians killed, and 16,000 women and children enslaved[49]. Edessa was systematically looted[50], its Records Office destroyed[51], and its famous churches, including the Hagia Sophia cathedral, regarded as one of the wonders of the world[52], were reduced to rubble and many replaced with mosques[53]. Almost every

[Above (enlarge): Another rare survivor of the obliteration of almost all of Edessa's Christian history since 1144. A 6th-7th century mosaic copy of the Image of Edessa/Shroud, found in the wall of a house[54] in Bireçik, a small town in Sanliurfa Province about 69 kilometres (43 miles) west of Edessa/Sanliurfa [see 25Apr16].]

vestige of Christian imagery in Edessa was ruthlessly destroyed as an offence to the Koran, making any survival of pictorial evidence of the Image of Edessa/Shroud's former presence in Edessa highly unlikely[55]. From this time on Edessa became a wholly Muslim city, with almost all traces of its former Christianity obliterated[56].

1147a In 1147 Louis VII, King of France (r. 1137-80) and Conrad III King of Germany (r.1138-52), enroute to Jerusalem in the Second Crusade (see 1147b below)[57], visited Constantinople[58, 59].

[Left (enlarge): Louis VII, King of France and Conrad III, King of Germany, entering Constantinople in 1147. Miniature by Jean Fouquet (1420–1481) in the Chronicles of St. Denis, 15th century.]

However Manuel was unable to contribute any Byzantine troops to the Second Crusade because his empire had just been invaded by Roger II of Sicily (r. 1130-54) and the Byzantine army was needed in the Peloponnese[60].

1147b The Second Crusade (1147-49) was the response by Latin (Roman Catholic) Christian Europe to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 and 1146 to Turkish Islamic forces[61]. (see above "1144" and "1146"). The crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III (r.1145- 53)[62] with the aim of restoring Edessa as the northern bulwark of the

[Right (enlarge): The Crusader States c.1140[63]. This map shows the strategic impossibility of Western European Latin Christianity (without help from Byzantine Eastern Greek Christ- ianity), defending Jerusalem as a Crusader state against the more numerous and organised Turkish Islamic forces.]

crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem[64]. Eugene commissioned the French abbot Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) to preach the case for a second Crusade[65]. Bernard in turn enlisted Kings Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany in 1146[66]. From Constantinople [see above], rather than taking the coastal road through Christian territory, Conrad took his army across Muslim-controlled Anatolia where it suffered heavy losses by the Seljuk Turks at the second Battle of Dorylaeum (1147)[67].

1147c In Constantinople Louis was entertained lavishly by the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r.1143-80)[68]. The Emperor took Louis to the Blachernae palace where he was shown the Shroud and venerated it[69]. Louis, after merging with the remains of Conrad's army followed a route closer to the Mediterranean coast but they were still attacked and weakened by the Turks along the way[70].

1148 The remnant of Louis' and Conrad's combined army reached Antioch by sea in 1148[71]. The military objective was Edessa but Louis wanted to complete his pilgrimage to Jerusalem[72]. However, in Jerusalem the preferred military target of King Baldwin III (1143–63) and the Knights Templar was Damascus[73]. But the Siege of Damascus in 1148 was another heavy defeat for the Crusader armies[74]. So the Second Crusade ended a disastrous failure[75], which left a bitter feeling in the West toward the Byzantine empire, because it could have done more to help[76]. This bitterness between West and East was no doubt a factor in the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Western troops enroute to the Fourth Crusade[77] [see "1204"].

c.1149 A copy of the Shroud face on a Crusader period (1131-69) painted column in the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem! "In the nave

[Above (enlarge): Extract from the cover of Rex Morgan's Shroud News, issue #54, August 1989. [See 04Aug16]. The caption is, "Crusader period painting of Christ in the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem: Another copy from the Shroud?" The photo was taken by the late archaeologist, Eugenia Nitowski (1947-2007) (aka Sr Damian of the Cross).]

of the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem are twenty-seven polished columns containing paintings of holy figures (c. 1130 and 1169)"[78]. Until 1131, the Church of the Nativity was used as the primary coronation church for crusader kings[79]. That is, from the coronation in 1100 of Baldwin I of Jerusalem (r.1100-1118)[80] to the coronation in 1131 of Baldwin I's granddaughter, Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem (r.1131-53)[81]. During this time and up to 1169, the crusaders made extensive decoration and restorations of the church and grounds[82].

This icon of Jesus' face dates from between c.1130 and 1169, and has, by my count, at least ten of the fifteen Vignon Markings: nos. 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 & 15 - especially no. 8 "enlarged left nostril", and therefore

[Above (enlarge): The Vignon markings: (1) Transverse streak across forehead, (2) three-sided `square' between brows, (3) V shape at bridge of nose, (4) second V within marking 2, (5) raised right eyebrow, (6) accentuated left cheek, (7) accentuated right cheek, (8) enlarged left nostril, (9) accentuated line between nose and upper lip, (10) heavy line under lower lip, (11) hairless area between lower lip and beard, (12) forked beard, (13) transverse line across throat, (14) heavily accentuated owlish eyes, (15) two strands of hair." [83]. [See 25Jul07, 29Jul08, 11Feb12, 22Sep12, 14Apr14, 09Nov15 and 15Feb16]

it is indeed "Another copy from the Shroud"! There are photos of the column online (e.g. "Jesus Christ Image on Pillar of Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem") but they are not high quality. Nevertheless, despite the poor quality of the photographs, it can be seen that this icon is very significant! Here is an icon on a pillar in the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem, which has at least 10 of the 15 Vignon Markings that are on the Shroud, and therefore it is beyond reasonable doubt this icon was based on the Shroud. Yet the icon is securely dated c. 1130-69, i.e. between 91 and 130 years before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud as "mediaeval ... AD 1260-1390"[84]! So this is yet another of the "lot of other evidence that" Oxford radiocarbon dating laboratory's Prof. Christopher Ramsey, who was involved in the 1988 dating and was a signatory to the 1989 Nature article admitted, "suggests [to put it mildly] ... that the Shroud is older than the radiocarbon dates allow" (my emphasis):

"There is a lot of other evidence that suggests to many that the Shroud is older than the radiocarbon dates allow and so further research is certainly needed. It is important that we continue to test the accuracy of the original radiocarbon tests as we are already doing. It is equally important that experts assess and reinterpret some of the other evidence. Only by doing this will people be able to arrive at a coherent history of the Shroud which takes into account and explains all of the available scientific and historical information."[85]c. 1150a A Christ Pantocrator ("Ruler of all"[86]) fresco, dating back to the twelfth century, in the rupestrian (cave) Church of St. Nicholas in Casalrotto, Italy[87]. Jesus' face is Shroud-like, rigidly forward-

[Above (enlarge): Christ Pantocrator centre panel of fresco between Mary and John the Baptist (see here), in the twelfth century cave church in Casalrotto, Italy[88]. See also 29Mar14 & 21Jun17.]

facing with Vignon markings including a forked beard, open staring eyes, a wisp of hair where the reversed `3' bloodstain is in the Shroud, and a triangle between the nose and the eyebrows[89].

c. 1150b The Christ Pantocrator mosaic in the apse of Cefalu Cathedral, Sicily[90] is among the most recent of many such

[Above: (enlarge): Christ Pantocrator, Cefalu Cathedral, Sicily[91].

"... if the radiocarbon dating is to be believed, there should be no evidence of our Shroud [before 1260]. The year 1260 was the earliest possible date for the Shroud's existence by radiocarbon dating's calculations. Yet artistic likenesses of Jesus originating well before 1260 can be seen to have an often striking affinity with the face on the Shroud ... Purely by way of example we may cite from the twelfth century the huge Christ Pantocrator mosaic that dominates the apse of the Norman Byzantine church at Cefalu, Sicily ..."[92].]works in the Byzantine tradition,which depict a Shroud-like, long-haired, fork-bearded, front-facing likeness of Christ[93]. But at c.1150 it is still over a century before the earliest 1260 radiocarbon date of the Shroud[94]. It has 14 out of 15 Vignon markings (see above)[95], including a triangle between the nose and the eyebrows, concave cheeks, asymmetrical and pronounced cheekbones, each found on the Shroud, and a double tuft of hair where the reversed `3' bloodstain is on the Shroud[96]. This means the artist was working from the face on the Shroud, copying each feature carefully, even though he did not understand what some of them were, for example the open, staring eyes are actually closed in photographic negative on the Shroud[97]. [See 29Mar14 & 21Jun17].

c. 1150 Installation of the "Window of the Passion and Resurrection"

[Right (enlarge)[98]. To help identify each panel in this "Passion and Resurrection" window, I created a grid reference: "L" and "R" for the left and right columns of panels, and 1 to 7 for the seven rows of panels. Thus "the crucifixion panel" above is grid reference L4.]

in the west wall of Chartres Cathedral[99]. King Louis VII (r. 1137-80) [see above] was both "well-learned and exceptionally devout"[100], and given the Byzantines' prohibition of literal depictions of the Shroud image[101], the short timeframe (1149-51), and that stained glass windows originated in medieval Europe in the 10th century[102], not Constantinople, it seems that Louis must have remembered the features he saw on the Shroud and on his return to France in 1149[103], had them depicted in these Chartres Cathedral stained glass windows [see 29Nov18d].

The "Flagellation panel" (below), at grid reference R3 (above right), has the following Shroud-like unusual features: 1) Jesus' crown of thorns is helmet-like (not wreath-like), as is the pattern of head puncture bloodstains on the Shroud [see 08Sep13a]. 2) Jesus' hands are crossed, right over left, awkwardly at the wrists, exactly as they are on the

[Above (enlarge). "The Flagellation panel" in the Window of the Passion and Resurrection, Chartres Cathedral[104].]

Shroud [see 29Nov18e]. 3) Jesus' hands and fingers are abnormally long, as they are on the Shroud, due to them being xray images of the Shroudman's finger and hand bones [see 20Apr17]. And 4) There are two scourgers, as evident from the pattern of scourge marks on the Shroud [see 15Jul13].

Continuing with my count of Shroud-like features, now in the "Crucifixion  panel" (above) at grid reference L4, 5) Jesus has a nail wound depicted in

panel" (above) at grid reference L4, 5) Jesus has a nail wound depicted in

[Left (enlarge): Extract from "the crucifixion panel" above, showing the nail wound in Jesus' right wrist (see below) and His body bent in a "Byzantine curve" (see below).]

his right (apparent because of mirror reversal) wrist, as on the Shroud [see below]. 6) His thumbs are retracted so they would not be visible from the back of the hand, as on the Shroud [see below]. 7) Jesus' abdomen is protruding, which was identified by French surgeon Dr Pierre Barbet (1884–1961) as evidence of the Shroudman's death by asphyxiation[105]. And 8) Jesus' right leg is depicted as shorter than his left, as appears on the Shroud [see below]. This is due to the Shroudman's left leg having been bent at the knee, his left foot placed over his right, and both feet transfixed to the cross by a single nail[106]. And then remaining fixed in that position by rigor mortis[107]. The

[Right (original)[108]: The frontal image of the Shroud (cropped). This is what the Byzantines and King Louis VII of France (r. 1137-80) would have seen [see above] when the Image of Edessa (the Shroud "four-doubled" - tetradiplon) was unfolded full-length. Note the nail wound in the Shroudman's right (apparent because of mirror reversal) wrist (see above); his hands are crossed, right over left, at the wrist (see above); his thumbs are not visible (see above); his hands and fingers appear to be abnormally long (see above); his abdomen is protruding (see above); and his right leg appears shorter than his left (see above).]

Byzantines thought Jesus was lame[109] (not realising that the Shroudman's legs only appear to be different lengths) and so they depicted Jesus' body in a compensatory "Byzantine curve"[110] [See "c.1001b"].

As mentioned at the beginning of this post (see above) Falcinelli discovered through his camera fitted with a telephoto lens, that in the "Crucifixion panel" (L4), Jesus is depicted with a realistic reversed `3', or epsilon (ε), bloodflow on his forehead[111] [see below and

[Above (enlarge): Falcinelli's telephotograph (left) and his highlighting (right), of the depiction of the Shroud's reversed `3', or epsilon (ε), forehead bloodstain [see below] in the c.1150 Chartres Cathedral stained glass window, "the crucifixion panel"[112]. This is Shroud-like feature 9) in this "window of the Passion and Resurrection" (see above) ogival stained glass window in the west wall of Chartres Cathedral.]

29Nov18b], exactly where the original is on the Shroud (see below)!

[Above (enlarge): The reversed `3', or epsilon (ε), and other bloodstains on the forehead and scalp of the man on the Shroud[113]. These bloodstains match the pattern of punctures by a crown (or rather cap or helmet) of thorns [see 08Sep13c].]

So this depiction of the Shroud's reversed `3' blood-stain at the exact same location on the face of Jesus in this c.1150 "the crucifixion panel" stained glass window in Chartres Cathedral, is yet another proof beyond reasonable doubt that the Shroud already existed in at least 1150, and therefore the mediaeval ... AD 1260-1390" radiocarbon date of the Shroud[114] was, and is, wrong!

Finally in the "Anointing panel" (L5) and below, Shroud-like features

[Above (enlarge): The "Anointing panel in the Window of the Passion and Resurrection, Chartres Cathedral[115].]

include: 10) Jesus' arms are crossed at the wrists, right over left, covering his pubic region; 11) His thumbs are not visible; 12) Jesus face has long hair and a forked beard, and 13) He is naked under his burial shroud. I have double-counted some of these features because they are on different panels and a sceptical alternative is that these are merely chance features, not based on any original model.

Therefore there are at least thirteen (13) unusual features on these three Chartres Cathedral stained glass window panels, dating from c.1150, that are found on the Shroud. One of these, Shroud-like feature 9), the reversed `3', or epsilon (ε), forehead bloodstain (above), is too specific to be explained away by Shroud sceptics as merely a chance similarity.

This discovery by Prof. Falcinelli of a realistic depiction of the Shroud's reversed `3' bloodstain (abov) in one of three Shroud-like depictions of Jesus in c.1150 stained glass windows in Chartres Cathedral, is at least as significant as the `poker holes' in the Pray Codex [see 21Aug18] in proving the Shroud pre-dated by at least a century its earliest 1260 radiocarbon date. That is because while sceptics can try to dismiss the Pray Codex as merely symbolic, they cannot so dismiss the Chartres Cathedral's literal reversed `3'! [see 29Nov18f] And there are at least thirteen unusual features in common between three of these stained glass windows and the Shroud (see below), compared with the Pray Codex's at least fourteen [see 04Oct18a].

Only a few days ago, in my scanning of the 118th and final issue of Rex Morgan's Shroud News (!), I read what Morgan had said in his keynote address at the 2001 Dallas Shroud conference:

"It is surely only a matter of time before someone comes up with hard evidence proving beyond dispute the whereabouts of the Shroud at some time in the first millennium. All the signs are there. Maybe we will find more clues amongst the ruins of Edessa, or in Constantinople, or tucked away in a medieval manuscript, as yet unseen in a hidden ancient library"[116].The Pray Codex alone already proved beyond reasonable dispute that the Shroud was at Constantinople (944) and before that in Edessa (544), in the first millennium. See above and my "Open letter to Professor Christopher Ramsey" [see 04Oct18b]. So these thirteen (13) Shroud-like features (including a realistic reversed `3' bloodstain in the same shape and location as on the Shroud), in these three c.1150 Chartres Cathedral stained glass windows, doubly proves beyond reasonable dispute that the Shroud was at Constantinople (from 944) and before that in Edessa (544-944), in the first millennium!

Continued in the next 12th century (2) of this series.

Notes

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to quote from any part of this post (but not the whole post), provided it includes a reference citing my name, its subject heading, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page.[return]

2. Email, "My studies on Shroud\Chartres," from Roberto Falcinelli, 28 November 2018, 2:15 am. [return]

3. "Knights Templar," Wikipedia, 24 September 2017. [return]

4. Currer-Briggs, N., 1984, "The Holy Grail and the Shroud of Christ: The Quest Renewed," ARA Publications: Maulden UK, p.17. [return]

5. Currer-Briggs, 1984, p.17. [return]

6. "File:Templars Burning.jpg," Wikimedia Commons, 7 June 2015. [return]

7. "Jacques de Molay: Death," Wikipedia, 11 September 2017. [return]

8. "Geoffroi de Charney: Death," Wikipedia, 19 September 2017. [return]

9. "Knights Templar: Arrests, charges and dissolution," Wikipedia, 24 September 2017. [return]

10. Wilson, I., 1978, "The Turin Shroud," Victor Gollancz: London, inside front cover. [return]

11. Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition, pp.178-179. [return]

12. Wilson, 1979, p.188. [return]

13. Wilson, 1979, p.188. [return]

14. Scavone, D.C., "The History of the Turin Shroud to the 14th C.," in Berard, A., ed., 1991, "History, Science, Theology and the Shroud," Symposium Proceedings, St. Louis Missouri, June 22-23, 1991, The Man in the Shroud Committee of Amarillo, Texas: Amarillo TX, pp.171-204, 197-198. [return]

15. "So obviously there remains an unexplained gap between 1204 and the 1350s (and my suggestion of Templar ownership during this period has never been more than tentative and provisional - please note that I no longer support the claims for this ..." (Wilson, I., 2012, "Discovering more of the Shroud's Early History: A promising new approach ...," Talk for the International Congress on the Holy Shroud in Spain, Aula Magna of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 28-30 April, 2012, p.2). [return]

16. Wilson, 1979, pp.158, 256, 312; Wilson, I., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London, pp.145-146; Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY, p.120. [return]

17. Drews, R., 1984, "In Search of the Shroud of Turin: New Light on Its History and Origins," Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham MD, p.47; Scavone, 1991, p.195. [return]

18. Wilson, 1979, pp.158, 312 n.7; Iannone, 1998, p.120. [return]

19. Scavone, D., "The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople: The Documentary Evidence," in Sutton, R.F., Jr., 1989a, "Daidalikon: Studies in Memory of Raymond V Schoder," Bolchazy Carducci Publishers: Wauconda IL, pp.311-329, 318. [return]

20. Green, M., 1969, "Enshrouded in Silence: In search of the First Millennium of the Holy Shroud," Ampleforth Journal, Vol. 74, No. 3, Autumn, pp.319-345; Wilcox, R.K., 1977, "Shroud," Macmillan: New York NY, p.94; Wilson, 1979, p.158-159; Wilson, 1986, p.114; Scavone, D.C., 1989b, "The Shroud of Turin: Opposing Viewpoints," Greenhaven Press: San Diego CA, p.88; Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1990, "The Shroud and the Controversy," Thomas Nelson Publishers: Nashville TN, p.78; Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London, p.152; Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY, p.270. [return]

21. Scavone, 1989b, pp.88-89; Wilson, 1998, p.270. [return]

22. Wilson, 1998, pp.144, 270. [return]

23. Wilcox, 1977, p.94; Wilson, 1979, pp.158, 257; Wilson, 1986, p.114; Wilson, 1991, pp.152-153; Wilson, 1998, pp.144, 270; Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London, pp.177, 301, 325; de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London, pp.382-383. [return]

24. Drews, 1984, p.47; Scavone, 1991, p.195. [return]

25. Beecher, P.A., 1928, "The Holy Shroud: Reply to the Rev. Herbert Thurston, S.J.," M.H. Gill & Son: Dublin, p.147. [return]

26. "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne," Wikipedia, 29 February 2016. [return]

27. Aebischer, P., 1965., "Le voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople," Librairie Droz: Amazon.com. [return]

28. "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne," Wikipedia, 29 February 2016. [return]

29. "Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne," Wikipedia, 29 February 2016. [return]

30. Beecher, 1928, p.147. [return]

31. Ibid. [return]

32. Adams, F.O., 1982, "Sindon: A Layman's Guide to the Shroud of Turin," Synergy Books: Tempe AZ, p.17. [return]

33. Wilson, 1998, p.269; Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London, p.109; Bennett, J., 2001, "Sacred Blood, Sacred Image: The Sudarium of Oviedo: New Evidence for the Authenticity of the Shroud of Turin," Ignatius Press: San Francisco CA, pp.145-147, 148; Wilson, 2010, p.50. [return]

34. Wilson, 1979, pp.95, 168-169; Adams, 1982, p.27, Dembowski, P.F., 1982, "Sindon in the Old French Chronicle of Robert de Clari," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 2, March, pp.13-18; Wilson, 1986, p.104; Scavone, 1989a, p.321; Stevenson & Habermas, 1990, p.79; Wilson, 1991, p.156; Iannone, 1998, pp.126-127; Wilson, 1998, pp.124-125, 142, 272; Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY, p.123; Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, p.8; Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition, pp.30-31; Wilson, 2010, pp.108, 186; de Wesselow, 2012, pp.175-176. [return]

35. "Peter the Deacon," Wikipedia, 22 September 2017. [return]

36. Barnes, A.S., 1934, "The Holy Shroud of Turin," Burns Oates & Washbourne: London, p.52; Currer-Briggs, 1984, p.16; Currer-Briggs, N., 1988a, "The Shroud and the Grail: A Modern Quest for the True Grail," St. Martin's Press: New York NY, p.62. [return]

37. Barnes, 1934, p.52; Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.62. [return]

38. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.62. [return]

39. Ibid. [return]

40. Ibid. [return]

41. Currer-Briggs, 1988a, p.62; Iannone, 1998, p.210. [return]

42. Wilson, 1998, p.270. [return]

43. "Siege of Edessa," Wikipedia, 12 June 2017. [return]

44. Wilson, 2010, p.146G. [return]

45. Wilson, 2010, p.119. [return]

46. Wilson, 1998, p.270. [return]

47. "Siege of Edessa: Aftermath," Wikipedia, 12 June 2017. [return]

48. Wilson, 1998, p.270. [return]

49. Wilson, 2010, p.301. [return]

50. Wilson, 2010, p.301. [return]

51. Wilson, 2010, p.118. [return]

52. Wilson, 2010, p.146F. [return]

53. Wilson, 2010, p.1. [return]

54. Wilson, 2010, pp.2-3, 210C. [return]

55. Wilson, 2010, pp.1-2. [return]

56. Wilson, 1998, p.270. [return]

57. "Louis VII of France: Early reign," Wikipedia, 28 September 2017. [return]

58. "Second Crusade: French route," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

59. "Conrad III of Germany: Life and reign," Wikipedia, 30 August 2017. [return]

60. "Second Crusade: French route," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

61. Latourette, K.S., 1953, "A History of Christianity: Volume 1: to A.D. 1500," Harper & Row: New York NY, Reprinted, 1975, p.411; "Second Crusade," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

62. "Second Crusade," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

63. "File:Asia minor 1140.jpg," Wikimedia Commons, 19 September 2016. [return]

64. Walker, W., 1959, "A History of the Christian Church," [1918], T. & T. Clark: Edinburgh, Revised, Reprinted, 1963, p.222. [return]

65. Latourette, 1953, p.411; Walker, 1959, p.222; "Second Crusade," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

66. Walker, 1959, p.222; "Second Crusade," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

67. "Conrad III of Germany: Life and reign," Wikipedia, 30 August 2017. [return]

68. "Second Crusade: French route," Wikipedia, 3 December 2018. [return]

69. Ricci, G., 1981, "The Holy Shroud," Center for the Study of the Passion of Christ and the Holy Shroud: Milwaukee WI, p.xxxv; Crispino, D.C., 1983, "Louis I, Duke of Savoy," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 7, June, pp.7-13, 12; Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1996, "The Enigma of the Shroud: A Challenge to Science," Scerri, L.J., transl., Publishers Enterprises Group: Malta, p.178; ; Iannone, 1998, p.120; Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN, p.58; Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, p.7; Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK, p.40; Fanti, G. & Malfi, P., 2015, "The Shroud of Turin: First Century after Christ!," Pan Stanford: Singapore, p.55. [return]

70. "Second Crusade: French route," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

71. "Second Crusade: Journey to Jerusalem," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

72. "Second Crusade: French route," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

73. "Second Crusade: Journey to Jerusalem," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

74. "Second Crusade: Siege of Damascus," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

75. Latourette, 1953, p.411; Walker, 1959, p.222. [return]

76. Latourette, 1953, p.411; Walker, 1959, p.222; . "Second Crusade: Aftermath," Wikipedia, 23 September 2017. [return]

77. Latourette, 1953, p.411; Walker, 1959, p.222. [return]

78. Mahoney, L., 2012, "Painted Columns in the Church of the Nativity," Encyclopedia of Medieval Pilgrimage, Brill’s Medieval Reference Library. [return]

79. "Church of the Nativity: Eleventh- and twelfth-century additions and restoration (c. 1050–1169)," Wikipedia, 13 September 2017. [return]

80. "Baldwin I of Jerusalem," Wikipedia, 3 September 2017. [return]

81. "Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem," Wikipedia, 26 September 2017. [return]

82. "Church of the Nativity: Eleventh- and twelfth-century additions and restoration (c. 1050–1169)," Wikipedia, 13 September 2017. [return]

83. Wilson, I., 1978, "The Turin Shroud," Book Club Associates: London, p.82e. [return]

84. Damon, P.E., et al., 1989, "Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin," Nature, Vol. 337, 16 February, pp.611-615, 611. [return]

85. Ramsey, C.B., 2008, "Shroud of Turin," Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, 23 March, Version 152, Issued 16 June 2015. [return]

86. Ruffin, 1999, p.110; Zodhiates, S., 1992, "The Complete Word Study Dictionary: New Testament," AMG Publishers: Chattanooga TN, Third printing, 1994, pp.1093-1094. [return]

87. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.193. [return]

88. Martino Miali, 2014, "Mottolo (Taranto). Church of St. Nicholas: fresco depicting Christ Almighty between Our Lady and St. John the Baptist. Photo by Martino Miali," Bridge Puglia & USA. [return]

89. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.193. [return]

90. Wilson, 1979, p.102; Maher, R.W., 1986, "Science, History, and the Shroud of Turin," Vantage Press: New York NY, p.82; Wilson, 1998, p.141; Antonacci, 2000, p.126. [return]

91. "File:Master of Cefalu 001 Christ Pantocrator adjusted.JPG," Wikipedia, 15 June 2010. [return]

92. Wilson, 1998, p.141. [return]

93. Wilson, 1986, p.105; Wilson, 1998, p.141. [return]

94. Wilson, 1986, p.104. [return]

95. Wilson, 1979, p.105; Maher, 1986, p.82. [return]

96. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.193. [return]

97. Wilson, 1979, p.105. [return]

98. Geoffrion, J., 2018, "Praying with Stained Glass Windows," Pray with Jill at Chartres. [return]

99. "Chartres Cathedral: Earlier buildings and the west façade," Wikipedia, 24 November 2018. [return]

100. "Louis VII of France: Early years," Wikipedia, 29 November 2018. [return]

101. de Wesselow, 2012, pp.180-181. [return]

102. "Medieval stained glass," Wikipedia, 16 July 2018. [return]

103. "Louis VII of France: Early years," Wikipedia, 29 November 2018. [return]

104. Falcinelli, 1998, p.9. [return]

105. Barbet, P., 1953, "A Doctor at Calvary," [1950], Earl of Wicklow, transl., Image Books: Garden City NY, Reprinted, 1963, p.86; Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1981, "Verdict on the Shroud: Evidence for the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ," Servant Books: Ann Arbor MI, p.45; Meacham, W., 1983, "The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology," Current Anthropology, Vol. 24, No. 3, June, pp.283-311, 285; Cruz, J.C., 1984, "Relics: The Shroud of Turin, the True Cross, the Blood of Januarius. ..: History, Mysticism, and the Catholic Church," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN, p.51; Maher, 1986, p.53; Borkan, 1995, p.27; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.114. [return]

106. Barnes, 1934, p.64; Brent, P. & Rolfe, D., 1978, "The Silent Witness: The Mysteries of the Turin Shroud Revealed," Futura Publications: London, p.46; Wilson, 1979, p.42; Morgan, R.H., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia, p.103; Wilson, 1986, pp.24-25; Borkan, M., 1995, "Ecce Homo?: Science and the Authenticity of the Turin Shroud," Vertices, Duke University, Vol. X, No. 2, Winter, pp.18-51, 24; Bucklin, R, 1998, "The Shroud of Turin: A Pathologist's Viewpoint," in Minor, M., Adler, A.D. & Piczek, I., eds., 2002, "The Shroud of Turin: Unraveling the Mystery: Proceedings of the 1998 Dallas Symposium," Alexander Books: Alexander NC, pp.271-279, 274; Iannone, 1998, p.59; Wilson, 1998, p.37; Antonacci, 2000, p.22; Tribbe, 2006, pp.94, 234-235; de Wesselow, 2012, p.145. [return]

107. Barnes, 1934, p.64; Borkan, 1995, p.24; Antonacci, 2000, p.32. [return]

108. Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002: Horizontal" (rotated left 90°), Sindonology.org. [return]

109. Barnes, 1934, p.68; O'Connell, P. & Carty, C., 1974, "The Holy Shroud and Four Visions," TAN: Rockford IL, p.6; Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1993, "Shrouded in Mystery," Shroud News, No 76, April, pp.14-21, 16; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, pp.13, 195-196; Tribbe, 2006, p.234. [return]

110. Barnes, 1934, pp.67-68; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.195. [return]

111. Falcinelli, 1998, p.4. [return]

112. File "Chartres-Schema volto1.JPG", emailed to me by Roberto Falcinelli, 28 November 2018, 2:15 am. [return]

113. Extract from Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Face Only Vertical," Sindonology.org. [return]

114. Damon, 1989, p.611. [return]

115. File "CHARTRES 2.jpg," emailed to me by Roberto Falcinelli, 28 November 2018, 2:15 am. [return]

116. Morgan, R.H., 2001, "The Shroud in the New Millennium," Keynote address given at the Dallas International Conference on 27 October 2001 by Rex Morgan," Shroud News, No. 118, December, pp.3-34, 32. [return]

Posted 23 September 2017. Updated 26 February 2025