Science and the Shroud (1) #34

This is "Science and the Shroud (1)," part #34 of my Turin Shroud Encyclopedia, which will help me write chapter 14, "Science and the Shroud," of my book in progress, "Shroud of Turin: Burial Sheet of Jesus!" See 06Jul17, 03Jun18, 04Apr22, 13Jul22, 8 Nov 22 & 20Jun24. I am basing this on my "Chronology of the Shroud: Nineteenth century," from "1898" onwards and "Twentieth century (1)" to 1902c.

[Index #1] [Previous: Objections answered (2) #33] [Next: Neutron flux #35]

1898a 25 May. In conjunction with the 1898 exposition of the Shroud over 8 days[JP78, 25; WI79, 26, 264; MR80, 122] from 25 May to 2 June[WI98, 298-299; MG99, 24], amateur but experienced Turin photographer Secondo Pia (1855–1941)[DT12, 18; SPW], took two 21 x 27 cm. test photographs of the Shroud[WI97; MG99, 25]. However, these reproduced poorly because of uneven lighting[WI97]. Nevertheless, although they were less than perfect, evident on these negatives was a strange effect[WI10, 18].

1898b 26 and 27 May. Three of Pia's fellow members of the Turin photography club, Prof. Noel Noguier de Malijay (1861-1930), Lt. Felice Fino and Fr Gianmaria Sanna Solaro smuggled their cameras into the exposition and took photographs of the Shroud[WI98, 298], which

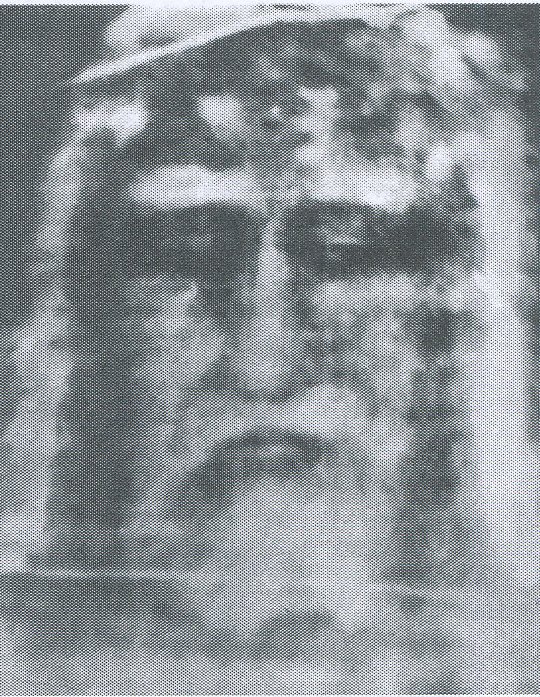

[Right (enlarge): Fr. Solaro's life-like negative of the Shroud face[FM15, 71]. As well as Solaro's photograph, Paul Vignon (1865-1943) also verified that a copy of Fino's negative photograph of the Shroud face, and that of a visitor to the exposition, were effectively identical to Pia's negative[VP02, 111]. de Malijay's photograph became lost[VM87, 9.]

when developed, confirmed Pia's discovery that the Shroudman's image is a photographic negative[OG85, 50; VM87, 9].

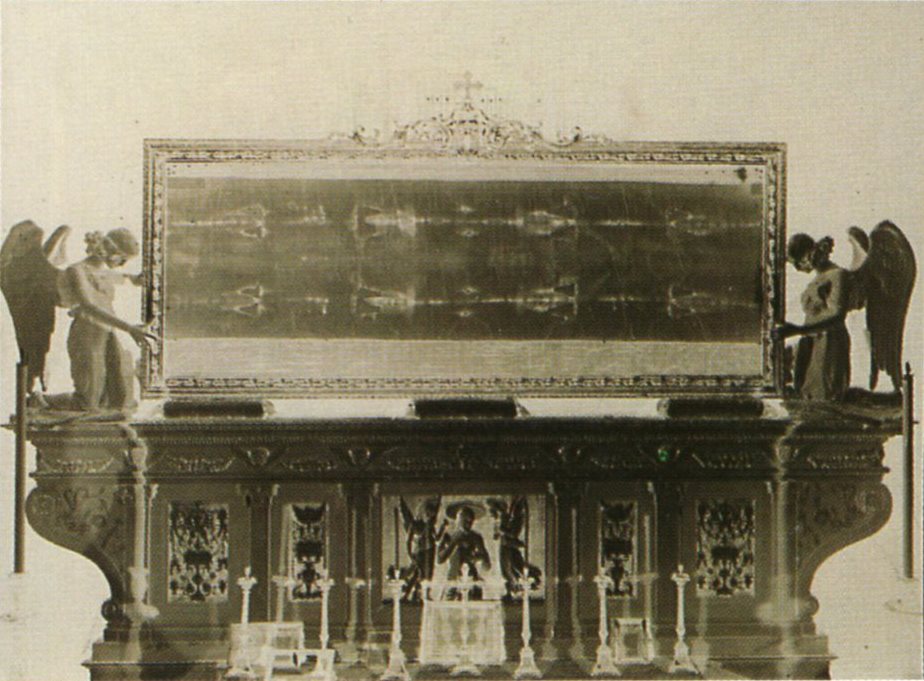

1898c 28 May. Pia took a further two 21 x 27 cm. test photographs and four 50 x 60 cm. official photographs of the Shroud[MG99, 25]. Around midnight in his home darkroom[WI79, 27; WJ63, 24-25; CJ84, 49; DT12, 18], as Pia was developing the fourth test photograph of the Shroud mounted over Turin Cathedral's altar (below), he was astonished to see on the emerging negative, that the strange effect which he had seen on the first two test photographs (see above)

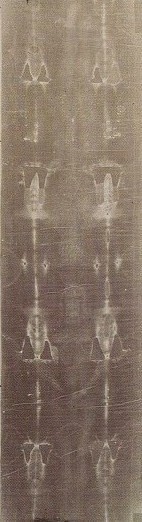

[Above (enlarge): Negative of Pia's fourth test photograph taken on 28 May[MG99, 24]. This is the actual negative photograph in which Pia first saw the Shroudman's life-like face.]

was real: the Shroudman's face on the negative had become life-like[MP78, 26; WI79, 27; IJ98, 5; WI98, 17; WI10, 18-19; DT12, 18-19],

[Above (enlarge[SP18]): Negative of the Shroudman's face by Secondo Pia, 1898. Presumably from one of his official photographs.]

as was the rest of his body[WM86, 10; RC99, 13]. Pia realised that the negative of the Shroudman's image is a photographic positive and therefore his image is a photographic negative[TF06, 54]!

The Shroud itself being inaccessible to scientists[MR80, 127; DT12, 100], Pia's photographs became the basis of scientific study of the Shroud[MR80, 126, 185; SH81, 30-31, 56; SR82, 41; OG85, 46; PM96, 213; IJ98, 191; GV01, 51, 156-157; TF06, 54; OM10, 195; DT12, 19-20, 100] for the next ~33 years[MR80, 127] (see future "1931") .

Despite the intention of the Shroud's owner, King Umberto I of Italy (r. 1878-1900) to, after informing the Vatican, make no public announcement until the implications of Pia's discovery were carefully considered, the news of leaked out[AF82, 54]. On 13 June the first press account of Pia's discovery was published in Genoa's Il Cittadino, followed by the national newspaper Corriere Nazionale on 14 June, and on 15 June the story of Pia's discovery was told in Rome's Osservatore Romano[WI98, 299]. No newspaper published Pia's Shroud negative, as photographs had not yet begun to appear in newspapers[AM00, 282]. However, the Christmas edition of the British photographic magazine Photogram published a large reproduction of Pia's photograph[WI98, 299]!

c. 1900. A small group of scientists at the Sorbonne Universty in Paris read the news articles about Pia's discovery and decided to start a scientific investigation into the Shroud[WE54, 17; WI79, 32; OM10, 170; DT12, 100]. The group included Rene Colson (1853-1941), physicist[WE54, 17], Paul Vignon, biologist[OA77, 4] , and Yves Delage (1854-1920), Professor of Comparative Anatomy[OA77, 4] and an agnostic[CJ84, 50-51; DR84, 4; BM95, 20; WI98, 299; AM00, 4; GV01, 51; DT12, 19, 117]. Vignon, who was the moving spirit of the group[WE54, 17], travelled to Turin to meet Pia and examine his Shroud photographic plates[VP02, 109; BR78, 36; MR80, 64]. Vignon satisfied himself of the genuineness of Pia's photographs and of Pia the man[VP02, 109; BR78, 36; MR80, 64]. Vignon returned to the Sorbonne with copies of Pia's photographic plates made by him for their scientific study[WE54, 17; DR84, 4].

That the Shroudman's image is a photographic negative is alone (and it is not alone) a fatal blow to the medieval forgery theory! Because: • The concept of photographic negativity only entered human knowledge when photography was invented in the middle of the nineteenth century[MR80, 64-65; SH81, 31, 57]. • Why would a medieval forger depict a negative image of Jesus on the Shroud when it could not be appreciated until it was photographed 5 centuries in the future[MR80, 65; SH81, 57]. • How could a medieval forger have the skill to depict the Shroud's fine anatomical detail when he would have been working blind, unable to check his work[MR80, 65; WM86, 10-11].

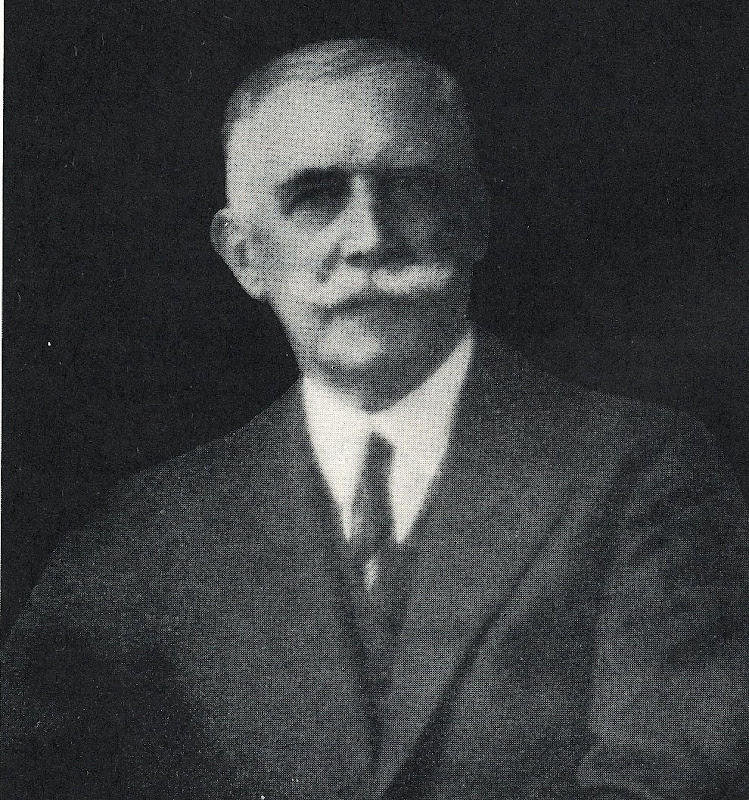

1902a. 21 April. Agnostic anatomy professor Yves Delage

[Left (enlarge)[FYD]. Portrait of Prof. Delage in 1911-12, by Mathurin Méheut (1882–1958)," Station Biologique de Roscoff, France].

(1854–1920)[GM69; MP78, 28; WI79, 32; SH81, 5; CJ84, 50-51; DR84, 4; BM95, 20; AM00, 4; GV01, 51; TF06, 185; OM10, 195; DT12, 117], a member of the French Academy of Sciences[WE54, 17; GM69], the foremost scientific body in the world at that time[MR80, 70; AM00, 4], reported the group's findings to the Academy, in a half-hour lecture titled, "The Image of Christ Visible on the Holy Shroud of Turin"[WJ63, 92; WI79, 32-33; GV01, 53; WI10, 31]. However, the Secretary of the Academy, Pierre Berthelot (1827-1907), an eminent thermo-chemist, was an atheist and he attempted to prevent Delage from presenting his report to the academy[WE54, 25; OG85, 68; AM00, 5; OM10, 196]. Then, after being overruled, Berthelot eliminated from the Proceedings of the Academy those parts of Delage's lecture which mentioned the Shroud and Christ[WE54, 25; AF82, 65; OG85, 68; AM00, 5; WI98, 298; WI10, 30; DT12, 20]! So on 31 May 1902, Delage wrote to the editor of Revue Scientifique, the eminent physiologist Charles Richet (1850-1935), who was to win the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1913, protesting Berthelot's censorship and including for publication in Revue Scientifique, the text of Delage's lecture which should have appeared in the Proceedings of the Academy[WE54, 26; WI79, 32; OG85, 68, 70-71; DT12, 20]!

Delage's points in Revue Scientifique were: • Negative The image on

[Right (enlarge): Extract of full-length negative of the Shroud from Pia's fourth test photograph of the Shroud above. Vignon would have been be working from a higher quality copy of this. As can be seen, if the Shroudman Jesus' image was a vaporograph, according to Delage and Vignon below, "The shroud was soaked in an emulsion of aloes ...", there would also be an image of the man's sides, since Jesus' body was "wrapped ... in a linen shroud" (Mt 27:59; Mk 15:46; Lk 23:53). That the man's image is only of his front and back, and not of his sides, is explained by STURP physicist John Jackson's "Cloth Collapse Theory"].

the shroud is a negative[DY02, 72; WE54, 18], in which light and dark are reversed[DY02, 72]. • Anatomical perfection The negative of the image reveals an unexpected anatomical perfection[DY02, 72; WE54, 18; WI79, 33; WI10, 30-31]. Head was repellent but after reversal of light and shade becomes admirable and expressive[DY02, 72; WE54, 19]. No head of Christ painted by Renaissance artists is superior to that of the ShroudDY02, 72]. • How was the image formed[DY02, 72; WJ63, 99]? Not by direct contact as it would be rough representation (see below)[DY02, 72]. • Painting for pious fraud[DY02, 72]? Rejected because Shroud is authenticated from the 14th century and if its was a faked painting the artist, who has remained unknown, would be superior to the greatest Renaissance painters[DY02, 72; WE54, 19]! Difficult enough to paint as positive[DY02, 72], but incredible to have been painted as a negative[DY02, 72]. Impossible except by photography, unknown in 14th century[DY02, 72]. Forger painting a negative needed to know how to distribute light and shade so that after reversal would give figure of Christ with perfect precision[DY02, 72]. Why would a medieval forger have taken this trouble when his forgery's beauty could only be appreciated after the invention of photography in the early 19th century[DY02, 72]? He would have been working for his contemporaries, not for the 20th century[DY02, 73]. • Image is realistic, without errors, non-traditional and conforming to no artistic style[DY02, 73]. • Blood which is not in the form of drops flowing immediately from the wounds, is strikingly realistic (Delage was both a Doctor of Medicine and a Doctor of Science[GM69])[DY02, 73]. • Scourging caused by dumbbell-shaped flagrum, unknown in the 14th century[DY02, 73]? Convergence towards points two scourgers' hands were[DY02, 73]. A medieval forger would not think of that[DY02, 73]. Compare medieval artists' pictures[DY02, 73]. • Naked. Most irreverent[DY02, 73]. A loincloth could not fail to have been added[DY02, 73]. A medieval Shroud intended for the faithful should not shock their feelings or scandalise them[DY02, 73-74]. Loincloths have been added to copies of the Shroud[DY02, 74]. • Nail wounds in the wrists not through the palms in conformity with anatomical requirements and against tradition[DY02, 74]. • No outline. Continuous gradation without sharp contours, different what an artist would depict[DY02, 74]. • Physio-chemical. Not a painting by the hand of man[DY02, 74; WJ63, 99]. Some physio-chemical process[DY02, 74]. How can a corpse produce on its enveloping shroud an image which reproduces its details[DY02, 74]? Not contact with body soiled with sweat and blood[DY02, 74]. Would be rough image and deformed when cloth is spread flat[DY02, 74]. • Projection. Image is an almost orthogonal projection[DY02, 74; WJ63, 99]. • Three-dimensional. Not Delage's word. Intensity of image at each point of the cloth varies inversely with the distance of that corresponding point of the body[DY02, 74]. This intensity decreases very rapidly and vanishes at a distance of a few centimetres[DY02, 74]. • Vaporograph. What radiation or image-producing substances can emanate from a corpse[DY02, 75]? The cloth was impregnated with an emulsion of aloes in olive oil, which contains a thin layer of aloetin, that becomes brown under alkaline vapours[DY02, 75]. This was Vignon's idea[DY02, 75]. The body was covered in febrile sweat rich in urea[DY02, 75]. The urea formed ammonium carbonate, which in a calm atmosphere, emitted vapours[DY02, 75], more diluted the further they were from the emitting surface[DY02, 76]. The shroud was soaked in an emulsion of aloes which became brown under the influence of alkaline vapours and formed a tint the more intense the nearer it was to the body's surface[DY02, 76]. Hence the negative image[DY02, 76].

Problems of the vaporograph theory: 1) If the "shroud was soaked in an emulsion of aloes which became brown under the influence of alkaline vapours" and formed "the negative image" then there would be an image on the man's sides, not only of his front and back (see above). 2) The "mixture of myrrh and aloes" spices in Jn 19:39-40 were not "on" (epi), nor "around" (peri), but "with" (meta), Jesus' body[BW57, 47]. That is, they were alongside Jesus' body[BW57, 97; WI79, 246]. So the aloes would only contact the side of Jesus' body, where there is no image (see above)! 3) Sweating is controlled by the central nervous system, so Jesus' would have stopped sweating when he died at "the ninth hour" (Mt 27:46-50; Mk 15:34-37; Lk 23:44-46), i.e. ~3pm. Jesus was entombed just before sunset (Lk 23:54), which would have been ~6pm[RTB], so Jesus' body would be cold after he had been dead for ~3 hours[RTB]. 3) Vapours don't travel in straight lines, but diffuse in all directions[PM96, 219]. So they would have diffused down through the cloth[PM96, 219], which they didn't because the man's image is extremely superficial (see 11Nov16) . 4) Vignon only had Pia's photographs, so he would not know that the Shroud image is not a substance added but is a physical change in the flax image fibres[see 11Jul16]. And 5) that the Shroud image is extremely superficial residing on the topmost fibres and not penetrating down through the thin Shroud cloth[RTB].

Identity of the corpse "Should I speak of the identity of the person who left his image on the shroud?" (my emphasis)[DY02, 76; WJ63, 100]. Unless this is a translation error, Delage sounds like a Shroudie! • On one hand we have the shroud impregnated with aloes - from the East outside Egypt[DY02, 76]. And a crucified man who had been scourged, pierced in his right side and crowned with thorns[DY02, 76; WJ63, 100]. On the other hand we have an account that Christ had undergone in Judea the same treatment as the image on the Shroud[DY02, 76]. Is it not natural to bring together these two parallel series and refer them to the same object[DY02, 76; WJ63, 100]? • For the image to be produced and not later destroyed, it is necessary that the body should remain in the Shroud at least 24 hours, the time necessary for the formation of the image and at most a few days, after which putrefaction destroys the image and finally the shroud[DY02, 76; WJ63, 101]. This is precisely what tradition asserts happened to Christ[DY02, 76]. Who died on Friday and disappeared on Sunday[DY02, 76]. • And, if not Christ it must be some criminal, but how is that to be reconciled with his admirably noble expression[DY02, 76]? • Probility not Jesus. Here Delage pioneered the `probability not Jesus' argument! Five circumstances (to mention only the principal ones), which are exceptional: East outside of Egypt, spear wound in side, crown of thorns, duration of burial and physiognomy[DY02, 77]. If for each there was 1 chance in 100 that each occurred in someone other than Jesus, that would be 1 chance in ten thousand million[DY02, 77]. [That is 10^(2+2+2+2+2) = 10^10 = 10, 000,000,000)]. Not exact but to show the improbability of all these conditions occurring in another person[DY02, 77]. Another person would be pure invention, not mentioned in history, tradition or legend[DY02, 77]. This is a good point to be used against the `crucified crusader' theory. Not Irrefutable but striking bundle of probabilities[DY02, 77]. • It is not scientific to shrug one's shoulders to avoid discussion[DY02, 77]. It is up to those opposed to Delage's arguments to refute them[DY02, 77]. They are not received by some because a religious question has been unfairly grafted on to this scientific question[DY02, 77]. • If it was not Christ but Sargon or Achilles or one of the Pharaohs, no one would have any objections[DY02, 77]. In refusing to insert my note in the Proceedings it has been forgotten that much more hypothetical theories have been published[DY02, 77]. But then there was no matters touching religion[DY02, 77]. ︎Conclusion. • "I have been faithful to the true spirit of Science in treating this question, intent only on the truth, not concerned in the least whether the truth would affect the interests of any religious; party. There are those, however, who have let themselves be swayed by this consideration and have betrayed the scientific method."[DY02, 79]. • "I consider Christ as a historical person and I see no reason why people hould be scandalised if there exists a material trace of his existence"[DY02, 79].

1902b April-May. Publication of French biologist and Roman Catholic colleague of  Delage, Paul Vignon (1865-1943)'s [Left [DP83].] important pro-Shroud book, Le linceul du Christ: étude scientifique (Masson et Cie, Paris)[WE54, 27; MP78, 28], followed in the same year by its English translation, "The Shroud of Christ" (Archibald Constable, Westminster)[TF06, 54; DT12, 100]. The results of the group's research were published in Vignon's book[ZT84, 31]. On the first page of Chapter I, Vignon stated:

Delage, Paul Vignon (1865-1943)'s [Left [DP83].] important pro-Shroud book, Le linceul du Christ: étude scientifique (Masson et Cie, Paris)[WE54, 27; MP78, 28], followed in the same year by its English translation, "The Shroud of Christ" (Archibald Constable, Westminster)[TF06, 54; DT12, 100]. The results of the group's research were published in Vignon's book[ZT84, 31]. On the first page of Chapter I, Vignon stated:

"Plain, simple observation will prove to us that the impressions are not the work of a painter, but they are the actual marks, left by a human body on the linen cloth-marks produced long ago by some action, other than direct contact, set up between the dead body and the linen cloth ... No one in the Middle Ages had the knowledge necessary for their production by handicraft"[VP02, 15]

Notes:

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to extract or quote from any part of it (but not the whole post), provided the extract or quote includes a reference citing my name, its title, its date, and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

Bibliography

AF82. Adams, F.O., 1982, "Sindon: A Layman's Guide to the Shroud of Turin," Synergy Books: Tempe AZ.

AM00. Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY.

BM95. Borkan, M., 1995, "Ecce Homo?: Science and the Authenticity of the Turin Shroud," Vertices, Duke University, Vol. X, No. 2, Winter, 18-51.

BR78. Brent, P. & Rolfe, D., 1978, "The Silent Witness: The Mysteries of the Turin Shroud Revealed," Futura Publications: London.

BW57. Bulst, W., 1957, "The Shroud of Turin," McKenna, S. & Galvin, J.J., transl., Bruce Publishing Co: Milwaukee WI.

CJ84. Cruz, J.C., 1984, "Relics: The Shroud of Turin, the True Cross, the Blood of Januarius. ..: History, Mysticism, and the Catholic Church," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN.

DR84. Drews, R., 1984, "In Search of the Shroud of Turin: New Light on Its History and Origins," Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham MD.

DT12. de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London.

DY02. Delage, Y., 1902, "Letter to M. Charles Richet," in Review scientifique, 31 May, in OG85, 70-80.

FM15. Fanti, G. & Malfi, P., 2015, "The Shroud of Turin: First Century after Christ!," Pan Stanford: Singapore.

FYD. File:Yves Delage. Photogravure. Wellcome L0012332.jpg, Wikimedia Commons, 7 September 2020.

GM69. Green, M., 1969, "Enshrouded in Silence: In search of the First Millennium of the Holy Shroud," Ampleforth Journal, Vol. 74, No. 3, Autumn, 319-345.

GV01. Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL.

IJ98. Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY.

JP78. Jennings, P., ed., 1978, "Face to Face with the Turin Shroud ," Mayhew-McCrimmon: Great Wakering UK.

MG99. Moretto, G., 1999, "The Shroud: A Guide," Neame, A., transl., Paulist Press: Mahwah NJ.

MP78. McNair, P., 1978, "The Shroud and History: Fantasy, Fake or Fact?," in JP78, 21-40.

MR80. Morgan, R.H., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia.

OG85. O'Rahilly, A. & Gaughan, J.A., ed., 1985, "The Crucified," Kingdom Books: Dublin.

OA77. Otterbein, A.J., 1977, "American Conference of Research on the Shroud of Turin," in SK77, 3-9.

PM96. Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1996, "The Enigma of the Shroud: A Challenge to Science," Scerri, L.J., transl., Publishers Enterprises Group: Malta.

OM10. Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK.

DP83. Extract from de Gail, P., 1983, "Paul Vignon," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 6, March, pp.46-50, 46.

RC99. Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN.

RTB. Reference(s) to be provided.

SH81. Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1981, "Verdict on the Shroud: Evidence for the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ," Servant Books: Ann Arbor MI.

SK77. Stevenson, K.E., ed., 1977, "Proceedings of the 1977 United States Conference of Research on The Shroud of Turin," Holy Shroud Guild: Bronx NY.

SP18. "SECONDO PIA (1855–1941): Shroud of Turin, c. 1898," Christie's 2024.

SPW. "Secondo Pia," Wikipedia, 1 April 2024.

SR82. Schwalbe, L.A. & Rogers, R.N., 1982, "Physics and Chemistry of the Shroud of Turin: A Summary of the 1978 Investigation," Analytica Chimica Acta, No. 135, 3-49.

TF06. Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition.

VP02. Vignon, P., 1902, "The Shroud of Christ," University Books: New York NY, Reprinted, 1970.

VM87. van Haelst, R. & Morgan, R., 1987, "Honouring an Almost Forgotten Shroud Scholar: Don Noguier de Malijay," Shroud News, No. 40, April, 8-10.

WE54. Wuenschel, E.A. 1954, "Self-Portrait of Christ: The Holy Shroud of Turin," Holy Shroud Guild: Esopus NY, Third printing, 1961.

WI79. Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus Christ?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition.

WI97. Wilson, I., 1997, "A Calendar of the Shroud for the Years 1694-1898," BSTS Newsletter, No. 45, June/July.

WI98. Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY.

WI10. Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London.

WJ63. Walsh, J.E., 1963, "The Shroud," Random House: New York NY.

WM86. Wilson, I. & Miller, V., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London.

WR10. Wilcox, R.K., 2010, "The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery," [1977], Regnery: Washington DC.

ZT84. Zeuli, T., 1984, "Jesus Christ is the Man of the Shroud," Shroud Spectrum International, No. 10, March, 29-33.

Posted 29 December 2024. Updated 8 February 2025.

.jpg)